Wyden seeks details on spies’ data protection after scathing CIA audit on Vault 7 leaks

A senator with insight into the way U.S. intelligence agencies conduct espionage wants to know if American spies are protecting their secrets in a way that prevents intruders from stealing information that’s crucial to national security.

In a letter sent Tuesday to the director of national intelligence, Sen. Ron Wyden, D-Ore., asked for more information about what he described as “widespread security problems across the intelligence community.” Wyden was referencing, in part, an internal Central Intelligence Agency audit that described “longstanding imbalances and lapses” in data protection before WikiLeaks published secret U.S. hacking tools, known as the Vault 7 files, starting in 2017. The October 2017 audit encouraged the CIA to view the audit’s findings as “a wake-up call” and “an opportunity” to “reorient how we view risk.”

Now, Wyden is asking Director of National Intelligence John Ratcliffe about whether known vulnerabilities still exist. The intelligence community “is still lagging behind, and has failed to adopt even the most basic cybersecurity technologies in widespread use elsewhere in the federal government,” Wyden said. He suggested the failures were caused, in part, by Congress’ exempting U.S. intelligence agencies from a requirement to implement cybersecurity directives from the Department of Homeland Security.

“CIA works to incorporate best-in-class technologies to keep ahead of and defend against ever-evolving threats,” CIA spokesman Timothy Barrett said in statement.

DNI did not respond to a request for comment.

The audit referenced in Wyden’s letter, which the senator also published in redacted form and provided to the Washington Post, detailed some of the weak cybersecurity measures that contributed to what the agency described as the largest leak in CIA history.

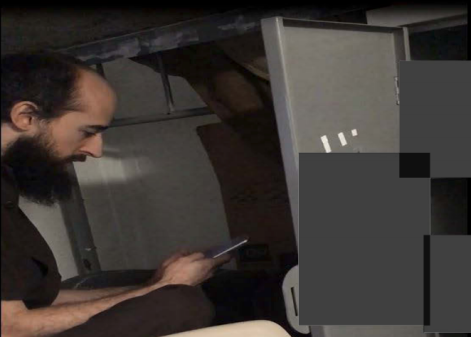

The government has accused Joshua Schulte, a former CIA employee, of stealing and leaking the Vault 7 hacking tools, which the CIA used to breach commercial technologies for cyber-espionage, though a jury in March was unable to reach a decision on his guilt. Schulte’s defense team had insisted through the trial that prosecutors in the Southern District of New York, and the CIA itself, would be unable to definitively prove the former CIA developer had a role in the Vault 7 disclosures because the software development networks (DevLAN) were so insecure that investigators simply could not determine who carried out the theft.

“We cannot determine the precise scope of the loss because, like other missions systems at that time, DevLAN did not require user activity monitoring or other safeguards that exist on our enterprise system,” states the internal CIA memo prepared for the agency’s then-director, Mike Pompeo, his deputy, Gina Haspel, who is now director, and former CIA chief operating officer Brian Bulatao.

“[I]n a press to meet growing and critical mission needs, [the CIA’s Center for Cyber Intelligence] had prioritized building cyber weapons at the expense of securing their own systems,” the document states later. “Day-to-day security practices had become woefully lax.”

The report, which was used in Schulte’s trial, determined that users shared administrator-level passwords, that there were no effective controls to mitigate risks from removable USB drives, an attack technique long used by hackers to steal or damage data, and that “historical data was available to users indefinitely.”

Testimony through the Schulte trial also highlighted personnel divisions, particularly between agency employees and outside contractors, over responsibility and management of the secret hacking tools. During his tenure as a CIA employee, witnesses said, Schulte would argue for more control of the software development process, and once disrupted a meeting between his supervisor and an outside contractor hired to take over some of his team’s work.

Internal disputes at the CIA motivated Schulte to steal and then leak U.S. secrets, the Department of Justice has alleged. Schulte has pleaded not guilty. Since a judge declared a mistrial, prosecutors have said they will try him again.

“People who worked in the CIA knew it wasn’t a protected system,” defense attorney Sabrina Shroff argued during her opening statement in February.

A person who worked on offensive CIA hacking tools until 2010 told CyberScoop that the report echoed some of the security shortcomings they experienced while on the job.

“They secured our operational computers with ZoneAlarm [security software] and duct tape,” the person said, speaking on the condition of anonymity to discuss their contracting work at CIA. “For really sensitive operations we had to add our own layers of security because we were so concerned about being hit.”

“The one thing that they did monitor for was porn,” the ex-CIA contractor said. “Which was odd…because we pulled down a lot of porn during our operations’ [incidental collection] so we would get flagged for that all the time, but basically nothing else.”

A redacted copy of the CIA’s findings and Sen. Wyden’s full letter are available below.

Sean Lyngaas contributed reporting.

Update, Thursday 9:00am ET: This story has been updated to include a response from the CIA.

[documentcloud url=”http://www.documentcloud.org/documents/6948258-Wyden-Cybersecurity-Lapses-Letter-to-Dni.html” responsive=true]