How Netgear and Trustwave built a virtuous cycle of vulnerability disclosure

Good news is rare in cybersecurity, but here’s some: Coordinated, responsible disclosure of software security gaps is increasingly the norm — and manufacturers are more and more willing to work with white-hat hackers who find bugs or flaws in their products.

It’s a virtuous cycle — researchers and manufacturers working together to make products more secure — that government wonks and academics are trying to encourage. In some cases, it also can be a story about what happens when cybersecurity becomes a kitchen-table issue and a market differentiator.

Router manufacturing giant Netgear and security firm Trustwave played out the cycle over the past year, and their story illustrates how vulnerability disclosure operates in practice, with all its limitations and tensions.

Last April, Trustwave researcher Simon Kenin contacted Netgear through its generic email address for reporting security issues. Kenin had found a software flaw affecting a number of its routers, making them vulnerable to what’s called a password disclosure attack. Such an attack lets a hacker remotely take over the router and thereby the entire home or business network it’s connecting to the internet. For a consumer that means losing control not just of a personal computer, but potentially a smart TV, automated home appliances and any other connected devices.

Chicago-based Trustwave initially didn’t have the smoothest interaction with the San Jose, California-based manufacturer.

“Netgear at the beginning were a little frustrating to deal with, to be honest,” Karl Sigler, threat intelligence manager for Trustwave, told CyberScoop in an interview.

Sigler said Trustwave’s responsible disclosure policy gives vendors or manufacturers 90 days to figure out a fix for the vulnerability and develop a patch before the company publishes its research. It’s an industry-standard deadline designed to ensure that vendors stay focussed on a fix, he said.

“An open window for patching doesn’t work,” he said.

In June, shortly before the 90-day deadline, Netgear published a little-noticed security advisory about the vulnerabilities Trustwave had emailed about in April. (The advisory has since been updated.) Netgear provided patches for some of the routers affected and workarounds that could protect others.

But since the initial disclosure, Kenin and his Trustwave colleagues had been looking at the bug and finding more ways in which different Netgear models were vulnerable.

After the June disclosure, Trustwave continued to work with Netgear on the vulnerabilities — and the growing number of router models impacted. But Sigler said Netgear was not always responsive.

It’s a common situation. The relationship between a manufacturer or vendor and a research firm can be fraught with tension. Researchers might think they are being stonewalled. Vendors may see disclosure deadlines as blackmail by publicity hounds.

“It wasn’t clear to us how seriously they were taking it,” said Sigler of how Netgear interacted with Trustwave over the summer.

Netgear Vice President of IT Tejas Shah says the company has always taken security seriously, but acknowledges that their generic security email address for vulnerability reporting was becoming overwhelmed last year.

“We were getting hundreds of emails,” he told CyberScoop.

Some researchers resorted to reporting security flaws through public user forums, Shah said. That was “Not good for them, because they got nothing out of it, not good for our customers because it was exposed and not good for us because we had no time to patch.”

Looking for help

In the end, Shah said, Netgear engaged Bugcrowd — a company that provides a platform for independent researchers to be rewarded for privately reporting vulnerabilities. Bugcrowd helped Netgear manage the gathering flood of reports.

“They helped us with the triage,” Shah said. “They helped us with communication.”

Bugcrowd and its competitors crowdsource the bug-hunting skills of independent researchers looking for flaws and vulnerabilities in the hope of winning cash prizes — to make the product more secure. The idea is that the more white-hat hackers scrutinize a product — so long as they are engaged with the manufacturers — the more secure the product becomes.

Other third-party vulnerability reporting channels, from the traditional Computer Emergency Readiness Teams or CERTs, to newer ideas like bug bounty programs, are also flourishing.

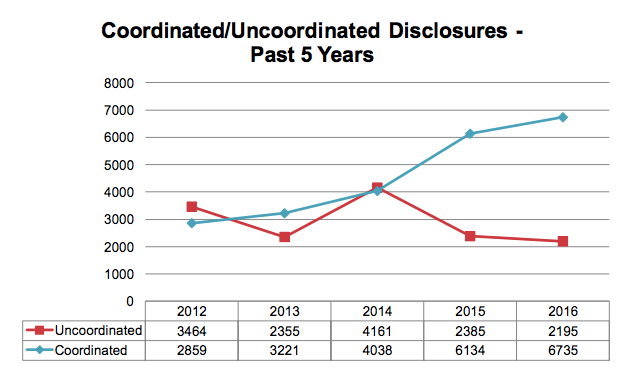

The proportion of vulnerabilities disclosed in coordination with third parties has risen from 26 percent in 2012 to 45 percent in 2016, and coordinated disclosures now outnumber uncoordinated ones more than three-to-one, according to figures compiled by Risk Based Security.

Source: Risk Based Security. The total number of vulnerabilities disclosed was 10663 in 2012 and 15,000 in 2016

Promoting responsible disclosure is the policy objective of a major consultation process that the National Telecommunications and Information Administration — an agency in the Commerce Department — is running with security researchers, software vendors and other stakeholders.

“It’s great to hear examples of organizations learning and adapting for better security,” said NTIA’s John Morris. He said his agency “is working with stakeholders to encourage this spirit of collaboration and promote awareness of the established standards and tools that can help organizations strengthen their cybersecurity practices.”

One of the objectives of the NTIA multi-stakeholder process is to figure out how the government can help counteract the market incentives that work against security — especially in the consumer sector, where the benefits of speed to market and usability tend to greatly outweigh the perceived costs of security.

A new threat landscape

That mission became easier in September. A widely publicized attack changed the dynamic for the Internet of Things in general — and it quickly altered the story line for Netgear and Trustwave.

The website of security blogger Brian Krebs was knocked offline by a huge distributed denial-of-service attack (DDoS) launched by the Mirai botnet.

Traditional botnets are large networks of personal computers taken over by malicious software or malware, generally unbeknownst to their owners, and used to send spam email or commit online bank fraud.

The Mirai malware was different. It took over routers and webcams — not PCs, but millions of other computerized devices connected to the internet and capable of collectively bombarding a site like Krebs’ with enough data to shut it down.

At the end of September, Mirai’s author published its source code — meaning anyone with even rudimentary computer skills could build their own botnet — and an attack orchestrated by an angry teenager brought several marquee internet and e-commerce sites to their knees.

It was a game-changer for the security landscape of connected consumer devices. And it made cybersecurity a board-level issue for the manufacturers like Netgear.

“It lit a fire under them, right when we were in the middle of the vulnerability disclosure process,” said Trustwave’s Sigler. “I think that they started taking the whole process more seriously. I could see changes occurring in who I was talking to and what their responses were … They were looking for guidance, they wanted to do the right thing.”

Getting security ‘into the DNA’

Throughout the fall of 2016, Trustwave continued to work with Netgear on the vulnerabilities Kenin had found — extending its usual deadline.

“Typically if they’re really communicating, if we can tell they’re really working hard on a patch, we can give them a extension” on the 90 day deadline, Trustwave’s Sigler said of working with manufacturers or vendors. “If they’re not communicative, if we can’t tell what they’re doing, we tend to hold pretty strictly to 90 days.”

But Netgear offered Trustwave “a really aggressive timeline,” and a promise to provide software updates that would fix the vulnerabilities in every model of affected router.

“We decided to delay our disclosure in order to give them a little more time to address the new routers that we had found [to be vulnerable] as well as to get patches out for the ones they hadn’t had time to patch” from the first disclosure, Sigler said.

Not all bug-hunters are so flexible. Many will publish when their deadline expires, regardless — as Google’s Project Zero has done with at least two Microsoft vulnerabilities this year.

Netgear’s Shah said that getting that external communication with the researchers right depends on the company’s internal process working well.

“The key here,” he explained, “is how efficient you are as a company when you find out about a security issue to prioritize it, to communicate with the [researchers] that found it and [figure out] how fast can it be solved … The challenge is to prioritize the fix.”

Shah said that now every Netgear product group meets “at least monthly” to review security issues, dealing with them according to priorities set by company-wide management and in fulfillment of internal service level agreements which specify strict deadlines for each stage of the fix process.

Shah added that security for routers had become “a new hot topic” last year — getting the attention of the CEO and board. “It’s not that we weren’t taking it seriously before but it’s top of everyone’s agenda now,” he said.

Shah said the Netgear philosophy was to “incorporate security into the DNA of the company — everyone should think about security all the way through the development process of a new product.”

News of the Mirai botnet put security at the top of the agenda in the boardroom — but it apparently also made it an issue in households all over. According to recent polling, consumers have begun to rate security as a factor they consider when buying connected devices.

“Netgear has a relatively good security posture,” Sigler said.

As the marketplace becomes more security conscious, he added, “Their open ear to listening to us and [other security researchers] will serve them very, very well.”

Security is part of Netgear’s “brand promise,” Shah said.

“If we don’t focus on security,” he said, “we will not survive in this industry.”