Ukrainian accused in cybercrime wave is considering trial in U.S., lawyer says

A lawyer for an alleged player in one of the largest hacking schemes in history says he is talking with the Department of Justice about the possibility of bringing his client to the U.S. to stand trial.

Mikhail Rytikov can’t leave his home country of Ukraine because he would risk becoming the latest Eastern European cybercrime suspect to be snatched up by Western law enforcement . The 30-year-old, who lives in Odessa on the coast of the Black Sea, allegedly participated in criminal schemes by running a profitable “bulletproof hosting” business — servers that police supposedly can’t block or access — known as AbdAllah.

Ukraine doesn’t extradite its own citizens, so Rytikov is theoretically safe as long as he stays close to home. But he vehemently denies any wrongdoing, and apparently wants to set the record straight.

His lawyer in the U.S., Arkady Bukh, told CyberScoop he is negotiating with the Department of Justice about the possibility of standing trial in federal court, on the condition that the government grants Rytikov bail. Without that, Rytikov’s team worries he would be jailed for years before the case went to trial.

“We are negotiating with the U.S. government for the possibility of him coming to the United States to try to prove his innocence,” Bukh said. “His main argument is that he does not deny he provided hosting services but he can’t guarantee who uses the hosting and for what purpose. But it’s very difficult to convince clients to come to the U.S. and trade the beautiful Black Sea for a jail cell on the Hudson, but if the government will promise to give him bail, he’s willing to come and explain his position.”

Rytikov faces charges in other countries, and there’s an Interpol Red Notice for his arrest.

The Department of Justice and Interpol declined to comment.

American authorities consider the arrest and extradition of alleged international hackers one of the most powerful — if one of the only — effective tools in their arsenal. It has happened so often in recent years that Russia claims the U.S. is “hunting” its citizens.

Some men in Rytikov’s position have gone deep into hiding. As he maintains his innocence, he’s living freely in Odessa, a city that’s a global hot spot for online organized criminal business like carding, bulletproof hosting and spam.

In Ukraine, Rytikov’s lawyers are suing the Department of Justice, the General Secretariat of Interpol, the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU), the General Prosecutor’s Office of Ukraine and the U.S. Embassy in Ukraine “for compensation for damage caused by illegal actions of the defendants,” Rytikov’s Ukrainian lawyer Artem Kravchenko said. Last month, Rytikov filed a letter in U.S. court protesting the “unlawful prosecution by U.S. law enforcement agencies over the last eight years.”

The men associated with Rytikov have not been so lucky. Two Russian cybercriminals received prison sentences in February in the case. They claimed that one of the largest and most lucrative hacking schemes in history — the victims included NASDAQ, Visa, 7-Eleven and Dow Jones — was run from hosting platforms controlled by Rytikov.

Authorities say the scheme was connected to a hacking group led by the American Albert Gonzalez (also known as “soupnazi”) who was sentenced to 20 years in prison after multiple successful breaches, numerous arrests, turning FBI informant and then stealing 160 million credit cards while employed by the U.S. government. It’s a one-of-a-kind pedigree.

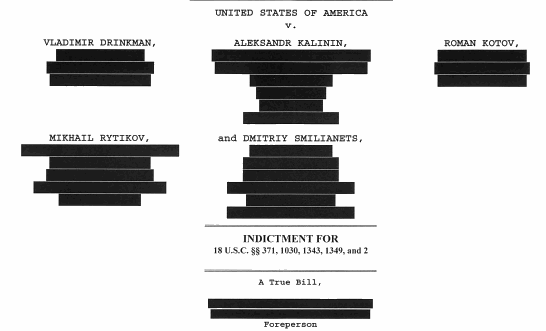

One U.S. indictment against Rytikov and four others.

Rytikov doesn’t deny that the hackers used his hosting service. Instead, he claims that his businesses are legitimate and that when major cybercriminals used them, they did so without his knowledge.

“He’s like a landlord renting to tenants without any malicious knowledge,” Bukh said. “That’s his argument.”

Landlords, however, can in fact be held legally responsible for crimes committed by tenants in certain situations — especially when the landlord’s services are advertised on underground cybercrime forums like AdbAllah’s business so frequently was.

Rytikov argues he never looked at what his customers were doing and therefore can’t be held responsible.

Hosting “generally does not involve interference in users’ activity and verification of the information placed by them on the provided physical space,” Rytikov’s Ukrainian lawyer, Artem Kravchenko, said. “Any verification of the content located on the server, in turn, is a direct violation of the users’ rights and is allowed only upon the complaints of the third parties concerning the illegal character of the posted information or upon the request of law enforcement agencies.”

Rytikov claims to have never received any such complaints until his offices were first raided in 2009. Further, he says U.S. officials have ignored all his subsequent appeals to discuss and cooperate on the case.

Look at the logs

The pseudonyms of AbdAllah (or Abdullah) and Whost lorded over a sizable criminal empire in bulletproof hosting, an industry that provides anonymous services to criminals who pay extra for protection from law enforcement. They go back to the days of the Russian Business Network, a cybercrime marketplace that once ranked among the world’s most active underground networks. It survived and thrived in large part thanks to political protection. AbdAllah advertised to the network’s criminals — and on many other sites just like it.

In another indictment against Rytikov, a long list of chat logs allegedly shows him knowingly communicating with another customer about how to host a credit card fraud website and avoid detection. In a criminal trial, the logs would deeply undercut and destroy Rytikov’s claim that he was unaware of what his hosting was being used for.

It wasn’t just ads, according to one Ukrainian intelligence official who spoke on the condition of anonymity because he wasn’t authorized to publicly discuss the case. The official worked the Rytikov case and was present on multiple raids on Rytikov’s property.

The Ukrainian intelligence official said Rytikov even at one point provided infrastructure for a Russian hacker named Evgeniy Bogachev, known online as Slavik, the author of the GameOver Zeus malware and a fugitive from the FBI with a $3 million reward on his head. Bogachev was known even then as a prolific cybercriminal.

Rytikov, under the name AbdAllah, was said to have filed a public grievance (known in the Russian-language cybercrime underground as a “black”) against Slavik for not paying him $30,000 for two months of hosting for Zeus’s infrastructure.

The Ukrainian official’s story goes further: Rytikov is also accused of hosting and moderating a section of Mazafaka, one of the most exclusive and Russian carding forums on the internet, and continues to advertise on other Russian-language cybercriminal forums across the net.

“So he definitely knows what’s going on,” said the official.

Familiar target

Rytikov’s businesses have been raided at least three times. In 2009, the same year the U.S. filed the first indictment against him, Rytikov was arrested and questioned as part of a raid by the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) and the FBI. He was released when he paid corrupt officials for his freedom, according to the former Ukrainian intelligence official, who was on the raid. The business was up and running again shortly.

The 2009 raid is when Rytikov began regular protection payments to corrupt Ukrainian SBU officers, according to the Ukrainian intelligence official. The payments continued for years, a story that’s all too common in Ukrainian policing and has contributed to a decline in morale among the country’s cybersecurity agencies. The SBU did not respond to a request for comment.

A Japanese request in 2013 led to a raid of Rytikov’s Odessa apartment because his data center at the time was well hidden, according to the Ukrainian official. He was let go again.

Finally, a 2016 FBI request led the SBU and an array of international police again to once again search Rytikov’s Odessa data center, the location of which was by then known, as well as a secondary Kiev data center connected to Rytikov’s company. By the time police arrived at the Odessa center, however, the place was empty. A neighbor told police he saw computer equipment being moved out just days before the raid.

“He was tipped by someone inside the service,” said the Ukrainian intelligence official, who was on the third raid. “I don’t think anyone can do anything to him. He cannot be extradited. He’s trying to sue everyone. No one wants to mess with him.”

The Ukrainian official’s side of the story — like the Department of Justice’s side and Rytikov’s — remains unconfirmed. SBU declined to comment.

After that last raid, the Ukrainian official said, Rytikov joked with the SBU that he would have to run for the Ukrainian parliament to join his pals. The joke was in reference to Dmitry Golobuv, a notorious cybercriminal turned elected Ukrainian politician and an icon in a world where cybercriminals are increasingly powerful players themselves.

You can read the full indictment against Rytikov below:

https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/4436264-Drinkman-Vladimir-Et-Al-Indictment-Comp.html