Fight over Kids Online Safety Act heats up as bill gains support in Congress

Newly reintroduced legislation that seeks to impose guardrails on tech companies in a bid to improve children’s mental health and safety is gaining support in Congress, yet faces growing opposition from civil liberties groups that say the bill would harm free speech and online privacy protections.

The Kids Online Safety Act, known as KOSA, would place a duty of care on platforms to prevent promoting to users under 17 content that includes harmful behaviors such as eating disorders and suicide. It would also require companies to give parents tools to supervise a minor’s use of a platform, including options to control safety settings. The bill would also require companies to allow independent audits and grant academic researchers data to make it easier to understand how social media is influencing young people.

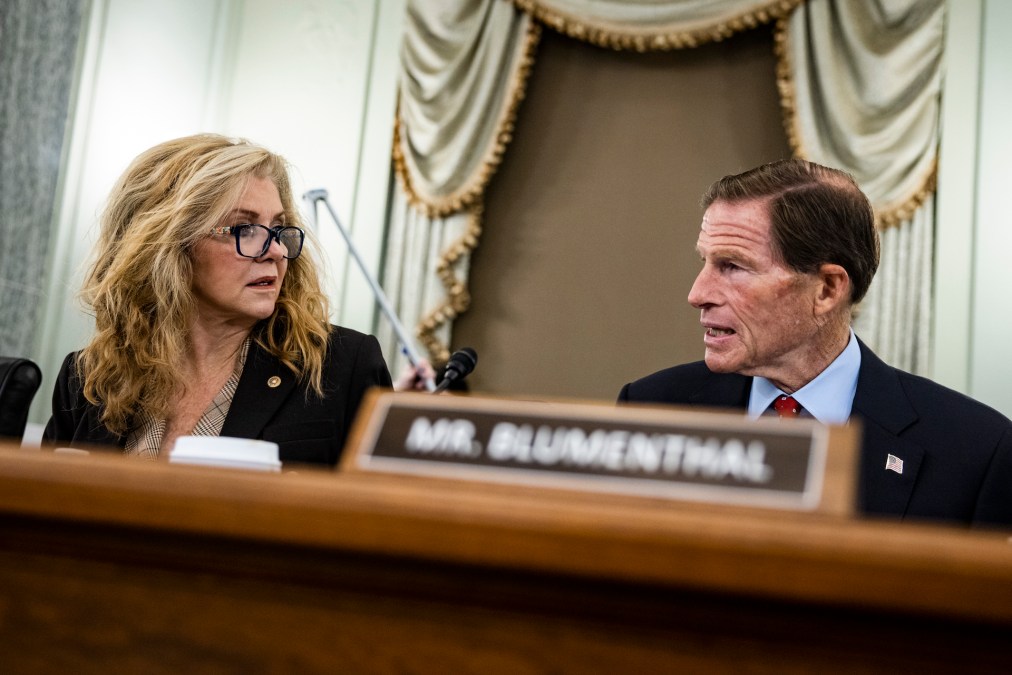

The latest version of KOSA, which was originally introduced last year by Sens. Richard Blumenthal, D.Conn, and Marsha Blackburn, R-Tenn., narrows how the duty of care aspect applies to tech companies. It specifies harms such as eating disorders and suicide as well as rules around data collection. The bill also carves out explicit protection for support services such as suicide help hotlines, schools and educational software.

“I think our bill is clarified and improved,” Sen. Richard Blumenthal, D-Conn., said at a press conference Tuesday that also included groups and parents supporting the bill. “We’re not going to solve all of the problems of the world with a single bill but we are making a measurable, very significant start.”

Advocacy organizations including the National Center on Sexual Exploitation, the American Academy of Pediatrics and Fairplay as well as a number of parent and youth advocates have thrown their support behind KOSA. At the press conference, several parents whose children died in social media-related incidents spoke in favor of the legislation.

Some critics of the bill, however, say the new changes do not address their concerns. “If an attorney general wants to argue that trans kids talking about going to a protest is making other kids depressed, they can do that,” says Fight for the Future director Evan Greer.

The bill also does not clearly distinguish what counts as a resource for mitigation or prevention, putting companies in the position of risking liability or avoiding recommending content about that topic altogether. When put in similar positions in the past, including the passage of SESTA-FOSTA, a bill passed in 2018 to help limit sex trafficking online, companies have been shown to choose the latter.

“There are two fatal flaws in this bill,” said Greer. “One is a misunderstanding of how platforms will react to this liability and the other is a fundamental misunderstanding of how technology works.”

Greer said that Blumenthal’s office has ignored several requests from the group to discuss the bill. Blumenthal’s office didn’t respond to a question specifically asking about the meeting requests.

The ACLU, which Blumenthal said the lawmakers had met with, also still opposes the law. “KOSA’s core approach still threatens the privacy, security and free expression of both minors and adults by deputizing platforms of all stripes to police their users and censor their content under the guise of a ‘duty of care,'” said Cody Venzke, senior policy counsel at ACLU. “KOSA would be a step backwards in making the internet a safer place for children and minors.”

Despite its critics, the bill appears to be outpacing other online safety efforts in Congress. The bill now has over 30 cosponsors in the Senate, more than double the last time it was introduced. Blumenthal says that Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., backs the legislation and a vote is a question of timing. “I fully hope and expect to have a vote this session,” Blumenthal said.

The bill hasn’t received unanimous support, however. And one of the leading lawmakers on privacy issues has major concerns.

“Giving extremist governors the power to decide what content is safe for kids online is a nonstarter,” Sen. Ron Wyden, D-Ore., wrote in a statement to CyberScoop. “However, I share the sponsors’ goal of making the internet safer for children and appreciate the bill’s effort to limit addictive design features targeted at children. I urge my colleagues to focus on elements that will truly protect kids, rather than handing MAGA Republicans more power to wage their culture war against kids.”

The bill lacks a companion in the House, where it could meet a stiffer reception from younger and more progressive members.

KOSA is just one of several pieces of children’s safety legislation that has received growing attention from civil society groups, though arguably it has garnered the most support. “It’s a DDoS of bills,” said Greer, referring to the flood of bills.”They’re trying to see which can get the most support and it seems like right now that’s KOSA.”

This week, members of the Senate Judiciary Committee are scheduled to mark up the EARN IT Act, another Blumenthal bill aimed at preventing online exploitation of children that has attracted concerns about the impact on free speech and potentially cornering companies into weakening their encryption.

On Tuesday, a group of 132 LGBTQ, privacy, free speech, and other human rights organizations led by the Center for Democracy and Technology sent a letter to Senate Judiciary Chair Dick Durbin, D-Il., and ranking member Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., the co-sponsor of EARN IT, urging them to oppose the bill. Separately, NetChoice, an industry association that includes Google, Meta, and Twitter among its members, also sent a letter to members of Congress asking them to reject the bill.

Durbin recently introduced similar legislation to crack down on online child exploitation, the STOP CSAM Act though it appears the bill will not be brought up for markup this week.

A bill introduced last week by Sens. Tom Cotton, R-Ark., Brian Schatz, D-Hawaii, Katie Britt, R-Ala., and Chris Murphy, D-Conn., would ban social media from kids under the age 13 and require parental consent for those under age 18.