North Korean hackers wanted investigators to think Russians hacked banks

A group of highly skilled bank-raiding hackers accused of working for the North Korean government is using tools that include computer code intended to make it appear like a Russian outfit is responsible, researchers say.

Cybersecurity researchers tell CyberScoop that the group, dubbed Lazarus, is fusing Russian language strings into its tools in an effort to confuse defenders and obfuscate attribution. The technique, discovered by Kaspersky and presented Monday at the company’s Security Analyst Summit in St. Maarten, shows how sophisticated threat actors will design attacks in ways that make it more difficult for forensic analysts to track their activity. Lazarus mostly recently has been accused of stealing $81 million from Bangladesh Bank, and was blamed for the infamous Sony hack.

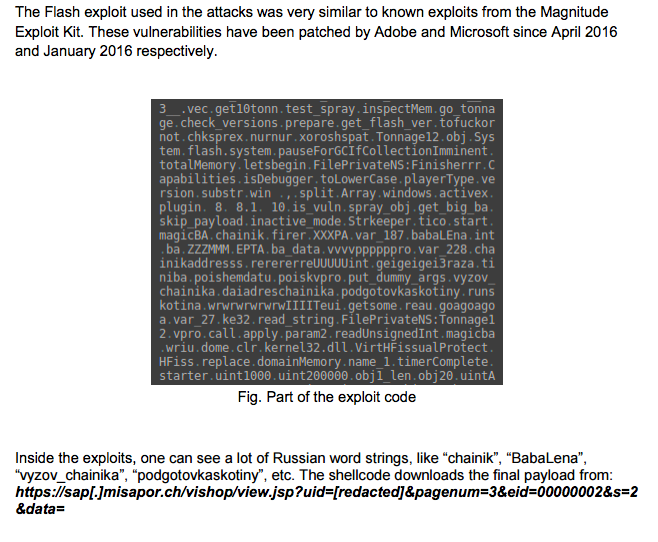

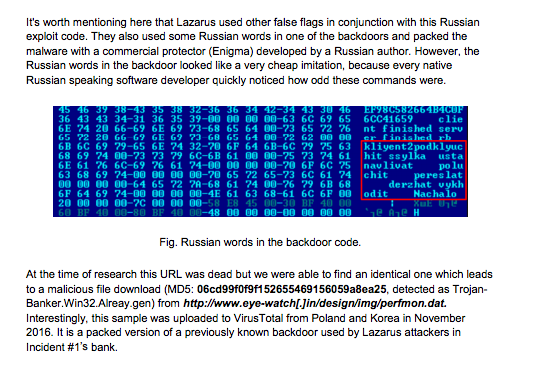

A set of outdated Adobe Flash Player and Microsoft Silverlight exploits repeatedly used by the Lazarus group carry Russian words like chainik, BabaLena, vyzov_chainika, and podgotovkaskotiny in the computer code. On a closer inspection, the commands themselves look odd, however, and a translation shows that the original developer likely had no language proficiency.

“The North Koreans are loud,” said Rendition InfoSec founder Jake Williams, “I’d guess it was intentional on the part of the Koreans, but why is anyone’s guess. False flags are part of their MO. They have repeatedly blamed destructive attacks on hacktivists … blaming someone else is par for the course for them.”

Lazarus’ Russian-themed Adobe Flash Player exploit is believed to have been once used against a group of Polish banks.

Screenshot from Kaspersky Lab’s “Lazarus Under the Hood” report

“The motivation seems to be a false flag, as they are not familiar with the intricacies of the Russian language,” a Kaspersky Lab spokesperson told CyberScoop of Lazarus’ Russian infused tools.

Security researchers have varying definitions for what exactly constitutes a “false flag,” and whether for example, obfuscation tactics should fall into that bucket.

Screenshot from Kaspersky Lab’s “Lazarus Under the Hood” report

Kaspersky Lab found that Lazarus also constructed a separate tool with components from Enigma, a commercial, off-the-shelf executable file protection program originally developed by a Russian author. The motivation to take code from Enigma isn’t clear — although it could be that the hackers wanted to add yet another layer of confusion or because they simply didn’t want to build the capability themselves.

Generally speaking, it’s not uncommon for advanced persistent threat groups, or APTs — a broad label used to define skilled hackers that typically serve governments — to employ proxies, foreign language strings, open source tools and compromised computer servers to help them hide their identities while launching different attacks.

In December 2014, cybersecurity firm Blue Coat — a now subsidiary of Symantec — discovered an APT group it dubbed Cloud Atlas that used exotic language strings and other foreign indicators to obfuscate their digital espionage operations. Though Cloud Atlas is believed to be Eastern European, different versions of the group’s malware carried hints that the developers wrote in Arabic, Hindi, Chinese and English.

“The presence of these various conflicting strings in different versions of the malware could either mean that the actors borrowed code from various sources to use in their implants, or that the strings were purposely placed to misguide researchers,” Kaspersky Lab researchers Brian Bartholomew and Juan Andres Guerrero-Saade wrote in an October 2016 research paper.

Attributing a cyberattack to a specific group or person is technically challenging for all of these reasons. And it’s why industry heavyweights like Symantec and Kaspersky generally tend to avoid making attribution assessments in publicly viewable reports.