Momentum builds to strengthen FTC’s role as privacy enforcer, though hurdles remain

When the White House nominated Alvaro Bedoya, a Georgetown law professor known for his expertise on privacy, for a role on the Federal Trade Commission, privacy advocates interpreted the move as the latest evidence that the agency is looking to expand its work investigating and bringing cases against companies that exploit and mismanage consumer data.

Bedoya, a former Senate Judiciary counsel who is known for his work addressing racial and gender bias on facial recognition technology and other surveillance of communities of color, comes with the promise of what privacy advocates envision for the future of the agency.

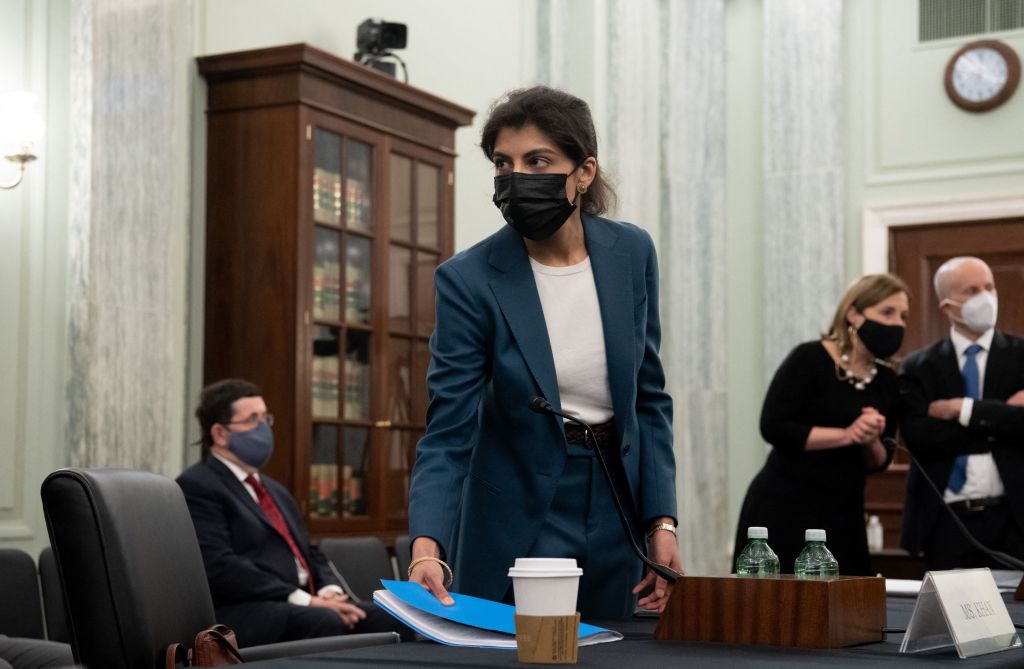

“Just as Lina Khan really sent a strong signal about taking the FTC seriously as an antitrust regulator, I think that the nomination of Alvaro Bedoya should send us the same signal to take the agency seriously as a privacy regulator,” said Christine Bannan, senior policy counsel at the Open Technology Institute, one of the many civil society groups that were quick to praise the nomination.

Bedoya’s nomination isn’t the only reason that privacy advocates, who have criticized the agency for what they consider insufficient settlements with tech giants like Facebook and Google over privacy violations, see new hope for the consumer watchdog to increase its tenacity.

House Democrats advanced a bill Tuesday that would set up a $1 billion dollar privacy bureau within the agency, a sum that’s three times the current operating budget of the entire consumer protection enforcer. The funding push comes in response to concerns that the agency lacks the resources and personnel to fill its mandate, a concern that’s been echoed by the agency’s commissioners themselves.

But experts and former FTC employees say that money alone probably won’t be enough to address long-standing criticisms of the agency’s ability to crack down on technology companies that violate consumer rights.

Today, consumers are up against a constant push by tech companies to gather deeply personal information about their lives and turn it for a profit — often without the security practices needed to protect that data. The FTC has to contend with billion-dollar firms like Facebook alongside a sea of relatively unknown smaller apps that do everything from collect health information to aid abusive stalkers.

Jessica Rich, former director at the bureau of consumer protection at the FTC, says the agency has always taken privacy seriously. However, its actions have been long hamstrung by its authorities.

“The problem at the FTC has been lack of authority and lack of resources,” says Rich, who is currently of counsel at Kelley Drye & Warren LLP.

Unlike in other countries with strong privacy regulators, the U.S. lacks a federal privacy law. While the FTC has brought a number of high-profile privacy cases, including a record $5 billion dollar penalty against Facebook in 2019 for violating an earlier agreement with the agency, the regulator’s authority on privacy is limited. It currently leans on its powers to take on consumer protection cases that involve “unfair or deceptive acts or practices.”

Often, that means companies can treat customer data as they wish, so long as they disclose it to customers, often in the privacy policy. Even if the FTC bring an “unfair or deceptive practices” case against the company, the agency generally cannot seek civil penalties for a first-time offense.

That authority means “the FTC can only be reactive, not proactive,” says Rich. In other words, the agency is limited to pursuing recourse only after wrongs are committed.

The current system has resulted in uncertainty in both what privacy-related cases the agency can pursue, as well as confusion for companies trying to stay on the agency’s good side.

“People want more clear rules, and one of the criticisms…is that the FTC privacy cases create kind of a common law that isn’t really law,” said Whitney Merrill, a privacy attorney who formerly worked at the FTC. “I think people look for compliance actions that they can take, but with the FTC’s authority being hooked on deception and unfairness that can be really hard.”

Companies would also welcome more guidance, says Aaron Cooper, vice president of global policy at BSA Software Alliance, a trade group that represents companies like Zoom and Microsoft.

“The FTC is going to make enforcement decisions, and if it put out guidance in advance saying ‘we think these practices are inherently unfair,’ that would be helpful,” said Cooper. “Whether that holds up is a different question, but at least it gives notice to industry and consumers.”

Cooper and others noted that Congress passing a federal privacy bill would relieve the FTC of having to make some of those rules.

“The FTC needs a privacy-specific law that covers the whole marketplace, not just specific sectors,” says Rich.

The agency could also benefit from having more tools to enforce those principles, such as the ability to fine companies for first-time violations, Rich says. Restoring the agency’s power to make rules under the Administrative Act. That should come along with a more streamlined rulemaking authority like that of the Federal Communications Commission.

Such authorities would give the agency the standing necessary to more aggressively enforce protections against discriminatory data practices and facial recognition software, two potential areas of focus hinted at by current leadership.

Failing action by Congress, the FTC has more limited options.

The majority of current commissioners in an April hearing expressed some support for using the agency’s Magnuson-Moss rulemaking power, a complicated process that would allow the FTC to write data protection rules regardless of Congress’s actions.

“Granted, a Mag-Moss rulemaking is not the first-best solution to address the myriad privacy issues confronting Americans today — federal privacy legislation is the optimal solution…[But] inaction is not an option,” Republican Commissioner Christine Wilson told the Senate Commerce Committee.

In July, the FTC voted along a party split to make the sometimes years-long process less cumbersome.

Barring any serious changes, the FTC could continue to take on privacy cases of course. But they would likely be tied to “low hanging fruit” such as clear data breaches, Merrill suggests. Ambitions like widespread penalties for discriminatory data practices and racially biased facial recognition technology, on the other hand, would be difficult to realize.

“I don’t think privacy will be taken seriously at a larger scale unless people actually feel like enforcement is coming,” says Merrill. “I think a lot of people think they can get away with a lot. If we want to get on the right path, we need clear rules and clear guidance and [the FTC has] to enforce.”