Deepfakes, dollars and ‘deep state’ fears: Inside the minds of election officials heading into 2024

Three years after a mob convinced that President Donald Trump had been the victim of widespread voter fraud stormed the U.S. Capitol, American election administrators are going into 2024 facing a daunting task: convincing the American electorate that the country’s elections are freely and fairly run.

If 2020 was challenging for election administrators, 2024 is expected to be far worse. Emerging technologies that might supercharge disinformation, a lack of resources, interference by foreign governments and widespread hostility from voters still suspicious of the electoral process are just some of the challenges they are expected to face.

Last week, many of the election officials expected to address these challenges convened in a small, ornate ballroom tucked away on the University of Maryland campus for a conference hosted by the Election Assistance Commission.

In interviews with CyberScoop and panel discussions, these election officials expressed a widespread sense of anxiety about the year ahead. Facing a lack of resources and widespread distrust, the officials responsible for running American elections are deeply worried.

“We’re not the enemy,” said Mark Earley, supervisor of elections for Leon County, Fla. “We’re not part of the deep state or whatever. We are just your neighbors and we’re out there getting the job done.”

We HAVA need for money, people

During past presidential election cycles, states have relied on hundreds of millions in federal dollars, either from extensions of funding from the 2002 Help America Vote Act or ad-hoc expenditures from Congress, to fund the running of elections.

In fiscal year 2022 and 2023 alone, the federal government doled out a total of $150 million in election security grants to states and territories, according to EAC figures. In 2019, Congress approved $425 million in one-time funding to states for election security and administration. Those dollars have helped support much of the bread and butter work done by election administrators, as well as improvements to voting and election technologies that have become integral to modern elections.

Last year, Sens. Amy Klobuchar, D-Minn., and Roy Blunt, R-Mo., pushed the EAC to expand the use of HAVA money for services to protect election workers from threats and harassment, while Klobuchar and 34 Senate colleagues also urged the Biden administration to include $5 billion in election security funding to states in its fiscal 2024 budget.

This year in a divided Congress, the prospects for a similar tranche of funding are slim. Rep. Steny Hoyer, D-Md., told CyberScoop that in past election cycles, extending HAVA funding “wasn’t a partisan vote,” but now Congress is “having great difficulty coming to agreement on where we ought to go.”

“It’s become a partisan vote because of this sense that somehow these guys are trying to steal the election or the maker of the [voting] machines was trying to do it,” Hoyer said.

With Election Day nine months away, any funds appropriated this year by Congress to fund elections will be too late to be put to use in 2024, according to election officials, though such funds could still help in preparing for future election cycles.

Gregg Amore, the Democratic Secretary of State for Rhode Island, told CyberScoop that his office has relied on funding from the Rhode Island state legislature this year but “an extension of the HAVA money is incredibly important” to states.

“It allows us to do training that we otherwise wouldn’t do. It allows us to do things technologically that we wouldn’t otherwise do,” Amore said. “We’re still working off old HAVA money and state money, but at some point beyond this election cycle, we’re not going to have those resources.”

Those sentiments were echoed by others, including Kentucky Assistant Secretary of State Jennifer Scutchfield, a Republican. Scutchfield said that election administrators in her state “always are underfunded” but that the state legislature has “done a phenomenal job over the last couple of years.

In their last biennial budget, Kentucky lawmakers allocated higher base funding for elections and added $12.5 million in funding to county clerks, something that allowed the state to move entirely to paper-based voting machines throughout the state, according to budget documents and testimony this year from Kentucky Secretary of State Michael Adams.

In past years, states have used federal funding to replace their paperless voting machines, beef up cyber protections around digital voter registration systems and hold cybersecurity-related trainings and exercises. Several officials said they are looking for ways to fund similar work this cycle.

“I would love to use [federal funding] to have more robust exercises. … Exercises cost money, so it would be nice to have that,” Washington Secretary of State Steve Hobbs, a Democrat, told CyberScoop. “I’d like to have more money to give to my local counties to help them.”

The New Hampshire AI robocall

State and local officials are expected to face a wave of disinformation this election, both the traditional kind that has dominated politics for generations as well as newer, AI-generated synthetic media that can convincingly mimic the voice and appearance of almost anyone.

A synthetically generated robocall imitating President Joe Biden directed at voters days before the New Hampshire primary marked the first such volley from bad actors during this election season, but no one expects it to be the last. Many officials admitted there is little they can do beyond referring voters to local election offices for the truth.

“I think everybody has to gear up for what’s going to be common, unfortunately, starting in 2024,” Heider Garcia, election administrator for Dallas County, Texas, told CyberScoop. “But the solution is the same: point people towards the actual sources of information.”

Several officials said the threat from AI-generated disinformation was already on their radar, but the New Hampshire robocall validated their fears that 2024 will see these kinds of technologies leveraged at scale and to directly target voter behavior. Others worried that it’s not just well-known politicians who have spent years on television or radio who can have their voice and appearance manipulated.

“That’s kind of my worst nightmare as an election official — is someone using an official voice or image to provide information that’s incorrect?” Christina Worrell Adkins, director of elections for Texas, told CyberScoop. “My voice is all over the internet.”

State and local election officials told CyberScoop that they’re responding to the threat through trainings and tabletop exercises at the state level or in tandem with federal partners like the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, while working with state legislators to craft new laws that would impose financial or criminal penalties for parties who use the technology to impersonate election workers or political candidates.

Hobbs, the top elections official in the state of Washington, worked with state lawmakers last year to pass a law that would require disclosure of deepfakes in election-related media and creates a private right of action for victims. Amore said his office is working with the Rhode Island state legislature on a bill that would require disclosure of deepfake use in elections, while Kentucky legislators have introduced a similar measure.

Meanwhile Minnesota, Arizona and other states have worked with CISA on exercises for how to respond to disinformation election deepfakes.According to figures provided by CISA’s press office, in 2023 the agency held 27 election-related tabletop exercises with states and counties and conducted 127 training sessions with more than 7,000 election officials on cyber, physical and operational risks.

On the federal level, recently introduced legislation would allow candidates for federal office to request court orders to halt the spread of AI-generated media depicting their likeness and to sue for damages. Agencies like the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency and the National Science Foundation are pouring hundreds of millions of dollars into research around technologies that can better detect and identify synthetically manipulated media. Nonprofits like Public Citizen are pressing the Federal Election Commission to propose new regulations that would interpret the use of deepfakes of political candidates under current laws governing election fraud.

But few expect a divided Congress to pass legislation on this issue or for regulation to be in place in time to impact the 2024 elections.

Meanwhile, an assessment by U.S. intelligence agencies last year found that foreign governments like Russia and China are likely to shift election interference efforts from targeting voting systems to “investing in technologies to better target and scale broader influence activities targeting the United States, particularly on social media.”

Drawing back the curtain on election administration

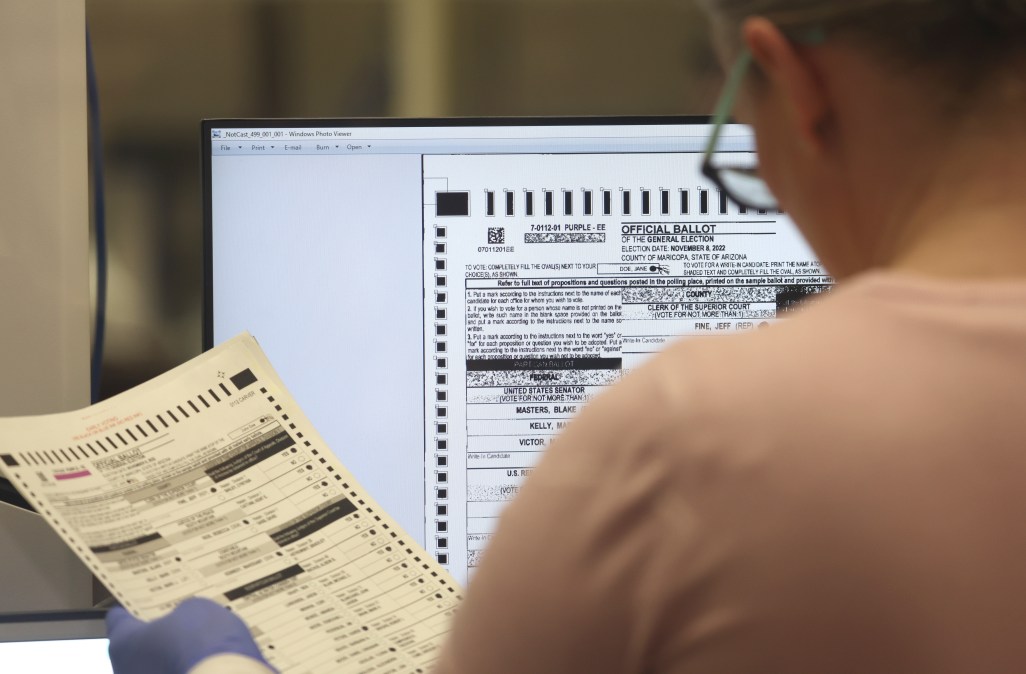

In the aftermath of 2020 and the widespread belief that voter fraud took place on a grand scale, many election officials realized that election administration is mysterious and complex to the average voter. The perceived complexity of a simple, local process makes many voters vulnerable to beliefs that poll workers and election officials may be part of a larger “deep state” conspiracy to rig elections.

Many states have responded with transparency, inviting skeptical voters to meet the people administering their elections and observe as they certify voting machines, conduct post-election audits and demonstrate the safeguards in place to prevent fraud and other wrongdoing.

Sherry Poland, director of the Hamilton County, Ohio, Board of Elections, said her county holds regular “Behind the Ballot” meetings where citizens, media and legislators can meet election staffers, receive technical briefings on voting machines and get a better idea of safeguards in place to prevent fraud. States like Florida, Rhode Island, Ohio and Texas offer similar programs.

Sometimes, election officials must direct those education efforts at lawmakers to address the risk that they peddle false or inaccurate information about voting processes.

Often, legislators are “hearing a lot of demands — not requests, but demands — from their voters,” Earley said. “If they don’t respond in some manner, they’ll get voted out of office and someone who is more malleable might be voted in. So we work to educate them.”

Doxing, swatting and white envelopes

Election officials face an increasingly hostile environment from voters who have become convinced the 2020 election was stolen. In many cases, those sentiments have spilled over into threats, harassment, doxing, swatting, bomb threats and dangerous mail targeting election officials.

A survey of election officials last year from the Brennan Center for Justice found that 30% had personally experienced abuse, harassment or threats over the past year, while 3 in 4 think these types of threats have increased in recent years. In addition to engagement and transparency, many officials spoke about investing in de-escalation trainings and other measures to calm angry voters convinced that votes are being manipulated.

Often, communication, explanation and de-escalation are not enough.

“I received an email with a bomb threat a couple of weeks ago and it shut down the entire [Kentucky] capitol,” Scutchfield told CyberScoop.“So I worry about myself. I worry about other election workers.”

Last year, envelopes filled with white powder were mailed to election offices in multiple states, with at least one testing positive for fentanyl. That incident is still being investigated by the FBI and the U.S. Postal Inspection Service.

Brendan Donahue, assistant inspector in charge at USPIS, said his “greatest concern” heading into the 2024 elections are “threats of violence and actual violence perpetrated against election officials and also election offices in this country.” He said USPIS and the FBI are working on guidance for election officials to identify suspicious packages in the future.

In addition to seeking cybersecurity assessments from CISA, Garcia said his Texas county is also seeking an assessment around physical hardening of election offices “where the ballots come in, where they sleep, where people work.”

Such assessments are about “making sure that all our doors are closed, that we don’t have any blind spots on cameras, that our alarm systems work,” Garcia said. And “that we have practice and drills in place in case there’s a fire, in case there is a need for evacuation.”