New Hampshire robocall kicks off era of AI-enabled election disinformation

Late in the afternoon on Sunday, Jan. 21, Kathy Sullivan received a text from a family member who said they had received a call from Sullivan or her husband and were following up.

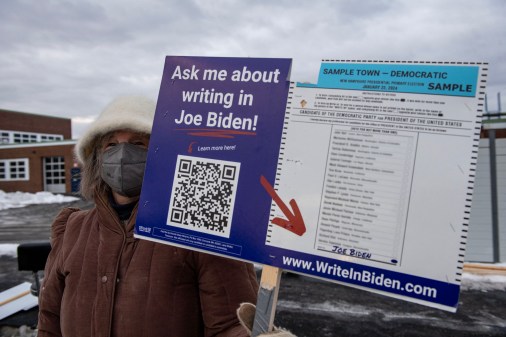

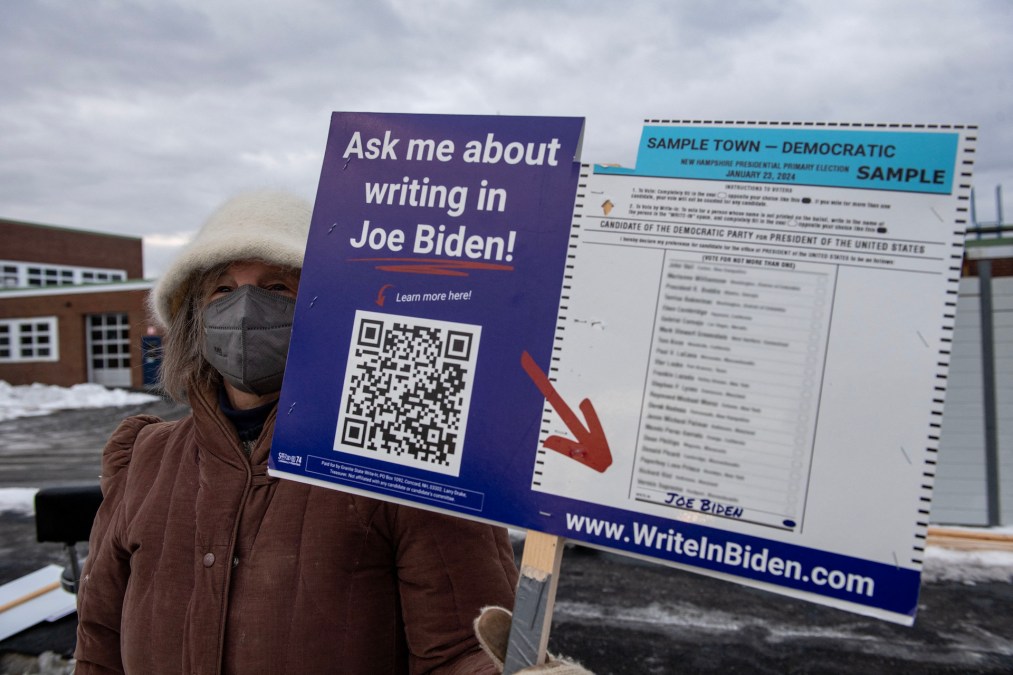

The treasurer of a super PAC running a write-in campaign for President Joe Biden in the New Hampshire primary election, Sullivan was busy with tasks ahead of an election only two days away. She dismissed the text and assumed the friend had been called by accident.

A few hours later, Sullivan was on her way out the door to dinner when she received another call, this time from a New Hampshire voter who inquired why she was sending automated voice messages of Biden to his phone. Baffled, Sullivan told him she had made no such calls and left without giving the incidents much more thought.

Halfway through dinner, Sullivan glanced at her phone and saw a dozen missed calls from numbers she didn’t recognize. That’s when she thought to herself, “Oh shoot, there’s something more here than I realize. Something is happening.”

Someone had begun flooding New Hampshire voters with a robocall that sounded like Biden warning Democrats not to vote in Tuesday’s primary because it “only enables the Republicans in their quest to elect Donald Trump.” The voice urged loyal Democrats to remember that “your vote makes a difference in November, not this Tuesday.”

Even stranger, the phone number that showed up on caller ID appeared to belong to Sullivan, the former New Hampshire Democratic state party chair. Whoever orchestrated the calls had spoofed her cell number, causing Sullivan to be bombarded with questions and complaints from New Hampshire voters.

What Sullivan had been fretting over turns out to have been a potential milestone in the 2024 U.S. election — what appears to be the first instance of AI-generated audio disinformation targeting American voters. It’s unlikely to be the last.

From the theoretical to the real

Technologists, cybersecurity specialists and government agencies have warned for years that AI tools could be used to create realistic images, videos and audio of people doing and saying things they never did. The New Hampshire robocall marks the moment when the possibility of bad actors leveraging deepfakes in the 2024 election became viscerally real.

“What we’re seeing now in New Hampshire is the application of this technology at scale,” Rex Booth, a former official at the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency and the Office of the National Cyber Director, told CyberScoop.

In this case, the actor behind the calls, as well as their ultimate motive, remains unknown. The impact of the call on voting behavior remains unclear, and Biden handily won his primary despite not appearing on the ballot.

While U.S. voters have already been exposed to deepfakes, misinformation and disinformation, the incident in New Hampshire shows how AI can be “applied in a way that has the ability to impact a larger number of potential voters faster, more immediately and in more relevant and direct ways,” said Booth, who is now the chief information security officer at the software company Sailpoint.

The past year has seen an explosion of AI-generated disinformation popping up in countries including Slovakia, the U.K., and Taiwan. While deepfakes have been used in American elections before, such as when the Republican National Committee released an AI-generated ad to describe an apocalyptic vision of the United States’s future if Biden were to be re-elected in 2024, the New Hampshire incident is the first time it’s been used to directly target U.S. voters and change their behavior at the polls.

“This was predictable and predicted,” Lindsay Gorman, a senior fellow for emerging technologies at the German Marshall Fund’s Alliance for Securing Democracy and a former senior White House advisor on AI, democracy and national security, told CyberScoop.

The proliferation of AI systems and the relative ease with which a person can be mimicked using deepfake technology — usually requiring audio of about an hour and sometimes as little as three minutes — means that the New Hampshire robocall is probably indicative of what is to come over the course of the 2024 election.

“I highly doubt this will be the last such incident that we see,” Gorman said.

Sullivan and others have filed a complaint with the New Hampshire Attorney General’s Office over the calls, though she acknowledged that she isn’t certain what state or federal laws may have been violated. New Hampshire law enforcement is already investigating the incident. Democratic members of Congress have called on U.S. Attorney General Merrick Garland to open a federal investigation.

“These messages appear to be an unlawful attempt to disrupt the New Hampshire Presidential Primary Election and to suppress New Hampshire voters,” the state Attorney General’s office said in a Jan. 23 statement.

“We gotta figure this out.”

In some ways, Sullivan was uniquely prepared to handle an incident like this. In 2002, she was the Democratic state party chair when GOP operatives carried out a phone-jamming scheme that aimed to disrupt her party’s get-out-the-vote operation in a closely contested Senate race. Four individuals, including Charles McGee, the executive director of the New Hampshire Republican Party, were charged and convicted or pleaded guilty on charges stemming from their roles in the incident.

In other ways, Sullivan is emblematic of just how ill-equipped many state and local officials are to handle AI threats. She describes herself as “not a technical person” and someone who before this week had only a general awareness regarding artificial intelligence, deepfakes and their potential impact on elections.

“Of course, now I’m extremely interested, and I’ll be paying a lot more attention,” Sullivan said.

The first line of defense against campaigns like the one in New Hampshire will be state and local election officials, many of whom are already dealing with a lack of resources and increasing hostility from voters suspicious of the electoral system.

Federal agencies like CISA have played a significant role in the combatting of disinformation in past elections, most notably through a “Rumor Control” web page that debunked various election-related conspiracy theories leading up to the 2020 elections.

However, a series of recent court rulings and a full-court press by Republican members of Congress, who have argued the federal government should not be in the business of policing disinformation, has significantly hampered the ability of agencies like CISA to engage with social media companies and coordinate with outside parties around disinformation.

For an agency whose founding director was summarily fired in 2020 after pushing back on election-related disinformation, the political scars and blowback have continued to linger.

“I don’t think CISA has either the appetite or the authority to wade into those waters again,” Booth said.

In a January op-ed published in Foreign Affairs, CISA Director Jen Easterly, senior election security advisor Cait Conley and Kansas Secretary of State Scott Schwab wrote that while federal support is needed, “in large part, responsibility for meeting this threat will fall to the country’s state and local election officials.”

“We gotta figure this out. We don’t have the capacity to do that, so we’re going to have to rely on some help from the nationals,” said Sullivan, who called on national party organizations and federal lawmakers to address the issue through trainings, resources and legislation.

Lessons learned

While the New Hampshire robocall was disruptive, Sullivan believes state and local officials can learn from the episode and how she and other officials responded to it. While many campaigns already employ rapid response teams for fast-breaking developments, that team should have some kind of plan in place for dealing with the emergence of fake or likely-fake media, Sullivan said.

“You’ve got to have people who are prepared to act at the drop of a hat. You have to be prepared for messaging, so you’re not taking three hours to figure out what to say in that blast email,” Sullivan argued.

In the case of New Hampshire, Sullivan and other party officials immediately moved to send out emails to supporters warning them of the fake audio and urging them to vote in Tuesday’s primary. They also reached out to media outlets in an effort to get broader coverage of the incident.

Lawyers on staff were tapped to quickly identify and contact relevant officials in law enforcement and the state attorney general’s office to report the call. Sullivan said that having those contacts in place saved precious time and contributed to a swift announcement issued Monday that state law enforcement was investigating the incident, something that might not have happened if they had cold-called authorities out of the blue with claims of AI-enabled election fraud.

But smaller campaigns and election offices may lack the resources to effectively respond to these incidents in real time. And as the 2024 campaign drags on, more obscure political campaigns may prove to be easier targets for AI disinformation, which could be harder to spot in less scrutinized races.

While the monotone and robotic cadence of the New Hampshire robocall may not have fooled voters familiar with Biden’s speaking style from decades of media exposure, voters might be more easily duped by a deepfake of a lesser-known candidate running for a state office. If that candidate has ever spoken at a public meeting or appeared in a television interview, the chances are there is sufficient audio and video of them in the public domain to create convincing deepfakes.

“I don’t know that anybody could have stopped this from happening, if somebody had the capacity to do it,” Sullivan said. “So how can we best be prepared?”