US, UK strike data transfer agreement

The United Kingdom and the United States finalized an agreement Thursday allowing for the free flow of online data between the two nations starting Oct. 12.

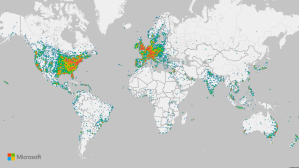

The data framework follows determinations by the United Kingdom that United States surveillance laws adequately protect their citizens’ data and provides assurances to technology companies that they won’t fall afoul of the law by transferring data belonging to their customers between data centers in the two countries.

After a series of European court rulings finding that U.S. surveillance law provides inadequate privacy protections and that the rights of Europeans might be violated when their personal data is transferred to data centers in the United States, policymakers in Washington have been hard at work to strike agreements with European states to address these concerns and allow data to flow more freely between the United States and Europe.

An executive order by the Biden administration last year containing a series of surveillance reforms, including redress for surveillance decisions in front of a new data protection review court, brought the United States up to par with both UK and EU mechanisms, paving the way for the agreement announced Thursday.

In July, the European Commission approved a similar data transfer agreement with the United States after years of negotiation.

The agreement announced Thursday faced fewer hurdles than the one the United States struck with the European Union, in part due to Washington and London’s intelligence-sharing partnership and similar surveillance programs.

“A U.S.-UK data bridge would uphold the rights of data subjects, facilitate responsible innovation, and provide individuals in both countries greater access to the services that suit them, whilst reducing the burdens on businesses and delivering better outcomes for people,” U.S. Secretary of Commerce Gina Raimondo and UK Secretary of State for Science, Innovation, and Technology the Chloe Smith said in a June statement.

For tech companies, the agreement provides reassurance that their operations can continue unimpeded, a huge boon for the economic relationship between the two countries. Transfers with the United States represent about 30% of the UK’s total global data-enabled services exports, according to government figures.

“It’s a big injection of confidence in the market,” said Joe Jones, director of research and insights for the International Association of Privacy Professionals.

Data transfer agreements could take on new importance as nations like the United Kingdom position themselves as a hub for AI research and development. Facing economic headwinds from the UK’s departure from the European Union, Prime Minister Rishi Sunak has in recent weeks pitched Britain as an attractive home for a new generation of AI companies. In November, the UK will host a global AI summit.

The inability to access and transfer data between the United States and the UK would represent an “existential challenge” to AI advancement, Jones said. “The integrity and safety of those models depend on datasets,” he added.

But there are still potential obstacles. There’s already a court challenge to the EU-U.S. agreement, which if successful could cause policymakers in the UK to reconsider whether U.S. intelligence reforms are considered adequate to protect the rights of their citizens.

Moreover, the United Kingdom will be looking at how United States lawmakers handle the renewal of Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance, the expansive powers of which are at the center of European complaints that the United States fails to respect European privacy concerns, according to Jones, who formerly served as the deputy director for international data transfers with the UK government.

The Biden administration is pushing lawmakers to renew the controversial surveillance authority, which currently allows U.S. intelligence agencies to collect the communications of non-U.S. persons abroad whose communications transit U.S. telecommunications systems without a warrant. In the process, U.S. intelligence agencies often sweep up the data of non-targets.

“The interpretation and the application of Section 702 is a key part of these adequacy decisions,” Jones said. “So the extent to which it no longer exists or changes is going to be relevant.”