Congress told ‘the market can’t fix’ poor cybersecurity at credit companies

The day after Halloween, lawmakers at a hearing on the Equifax breach heard scary stories of an under-regulated industry that collects and analyzes vast quantities of data about consumers without their knowledge or consent, stores it insecurely and sells it to the highest bidder.

Representatives of the credit reporting industry told the House Energy and Commerce Subcommittee on Digital Commerce and Consumer Protection that those were all campfire tales to frighten children and that searching for a legislative solution would be the governmental equivalent of a snipe hunt. And Republican lawmakers sought to tamp down industry concerns by saying they were still in the information-gathering phase of their work.

The hearing, said subcommittee Chairman Bob Latta, R-Ohio, “is an important step toward answering the many questions that consumers are asking.”

But the overall tone of proceedings, even from the credit reporting industry’s traditional allies in the GOP, was not at all friendly.

“Consumers are getting taken to the woodshed, companies are making billions of dollars off our data and we’ve had it,” said Greg Walden, R-Ore., the chairman of the powerful full Energy and Commerce Committee.

“Equifax’s entire business model is predicated on collecting and securing an individual’s private financial history,” his opening statement said. “It failed, and now Equifax must face serious consequences.”

He noted that there are many laws on the books already that require such businesses to take steps to secure customers’ data.

A “highly regulated” industry

Francis Creighton, the president and CEO of the Consumer Data Industry Association, a lobbying group that represents Equifax and the other major credit reporting companies, agreed. In the wake of the breach, he said, some commentary had suggested that the credit reporting system was unregulated, leaving consumers unprotected.

“Nothing could be further from the truth,” Creighton said. “This industry is highly regulated.”

He called the U.S. credit system “accountable and color-blind,” and “the most democratic and fair credit system ever to exist” because it was based “solely on [a consumer’s] own personal history of handling credit.”

He said the system is “the envy of the world,” calling it “one of the main reasons American consumers have such a diverse range of lenders and [credit] products from which to choose.”

Nonetheless, he pledged to lawmakers that “if in the course of the investigation [into the Equifax breach], we find a regulatory gap, we pledge to work with you” to fill it.

Democrats’ assessment of the state of the industry was much less rosy.

Consumers are the product

“We are not the customers, we are the product,” said New Jersey Rep. Frank Pallone, the full Energy and Commerce Committee’s ranking Democrat. Equifax “did nothing” to secure consumers’ data “and had no incentive to do anything. There are massive loopholes in existing law and regulation,” he added.

Referring to Walden’s comment about the breach — “You can’t fix stupid” — Pallone countered: “Breaches are not the result of stupidity. They happen because the companies don’t invest in security.”

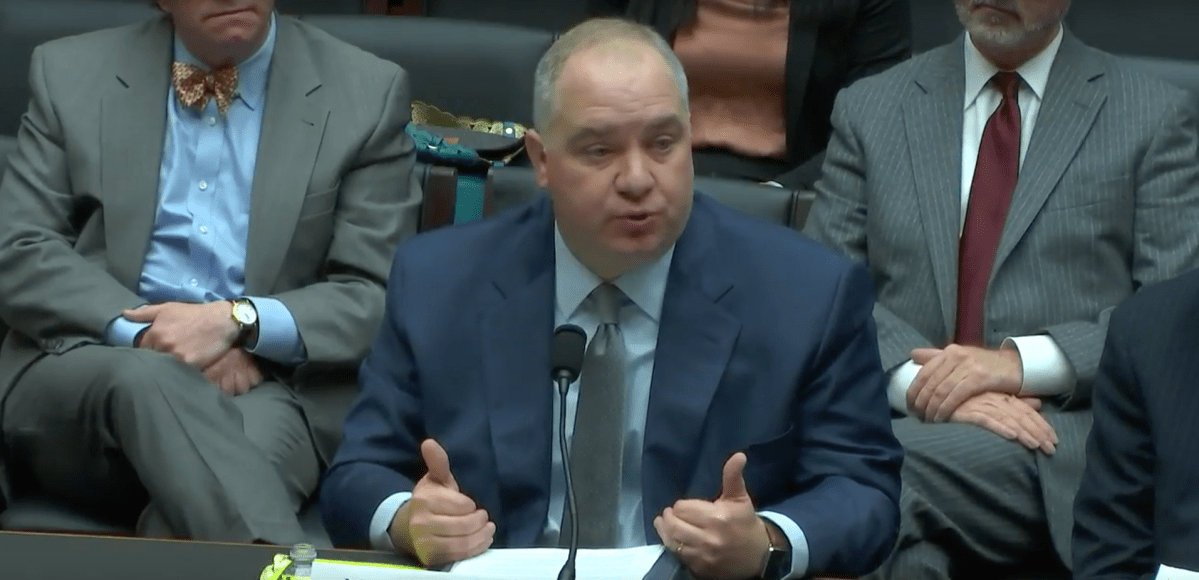

Cybersecurity expert and privacy maven Bruce Schneier agreed.

“Equifax’s security really was laughably bad both before during and after” the breach, he said. There were no penalties for failure from the market and no meaningful ones from the regulators. “If you are the CEO of Equifax and you have a choice to save 5 percent on your budget by underspending on security … by taking a chance, you’re going to take that chance.”

Richard Smith, the Equifax CEO who retired shortly after the breach, “left with an $18 million pension, he’s doing OK,” said Schneier, an adjunct faculty at the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard.

“The market can’t fix this … because we are the product,” he said.

Incentives, incentives, incentives

At least one Republican seemed to agree. Texas GOP Rep. Joe Barton said that if the company had known it would pay $50 per consumer if it didn’t fix this security problem, “I believe they would have fixed it.”

In fact, Schneier said, the market incentives operated in the other direction — toward a lack of security.

“The credit companies want to make it as easy as possible for you to get a new card … If they made it more secure, made it harder for someone else to get a card in your name, that would make it harder for you and the companies don’t want that. So they make that trade off based on their bottom line not on your security,” he said.

Anne Fortney, a lawyer who worked for the Federal Trade Commission in the 1970s and ’80s, pushed back against that argument. Data privacy, she said “Is not an area where they cut costs.” But she acknowledged the was a trade off between consumers’ rights to control their financial information and the industry’s need to access it — to the benefit of all, since it enabled credit decisions to be made swiftly and fairly.

“In sum,” she concluded, “There is a tradeoff between consumers’ right to privacy of their personal information and the commercial needs and benefits of that information and our laws reflect that balance in the tradeoff.”

Schneier advocated a nationwide credit freeze — where consumers would have to agree to their report being accessed. At the moment, consumers have to affirmatively ask for a freeze. “There’s no reason why my credit score should be given out without my permission … if I’m applying for a car loan or mortgage I’m going to know,” he said.

The move wouldn’t improve the cybersecurity of credit reporting companies but would make breached data and the identity theft it can facilitate harder to monetize, he said.

Lawmakers, make laws

Former Bush administration Homeland Security official James Norton urged lawmakers to “resist the temptation to put in place rules and regulations that require companies and institutions to take specific federally approved actions to address cybersecurity issues.”

Such proscriptive mandates would create “limited flexibility for private sector companies to respond to emerging threats,” he said. Instead, Congress and federal agencies should commit to “working collaboratively with businesses and consumers to share information and best practices about cyber threats.”

Democrats didn’t seem to be listening.

“Ultimately, we need stronger legislation,” said Jan Schakowsky of Illinois, the subcommittee’s top Democrat. She and other subcommittee members recently introduced legislation — the Secure and Protect Americans’ Data Act — that she said sets “data security requirements to protect consumers’ personal information” and empowered the FTC to enforce them with civil penalties. The bill also would set national standards for “timely notification to state and federal law enforcement agencies and to consumers when a data breach occurs,” she said.

The bill also would mandate “meaningful remedies for breach victims” who would be entitled to 10 years of free credit monitoring or quarterly credit reports,” she said.