Hacks, leaks and wipers: Google analyzes a year of Russian cyberattacks on Ukraine

On March 16, 2022, just weeks after the start of Russia’s assault on Ukraine, hackers attacked an unnamed Ukrainian organization with destructive malware designed to wipe its hard drives. The same day, suspected Russian attackers infiltrated a Ukrainian media company to spread a bogus story that Kyiv would surrender to Moscow. Soon thereafter, a crude deepfake appeared online showing Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy saying the country would soon give up its fight.

That sequence of events, which occurred as fighting intensified, exemplifies how Russia executed its hybrid approach to warfare — with mixed results — over the past year, combining the use of digital weapons and online propaganda alongside traditional military operations in an attempt to win its brutal campaign.

There’s “a pattern of concurrent disruptive attacks, espionage, and [information operations] — likely the first instance of all three being conducted simultaneously by state actors in a conventional war,” according to a new report from Google’s Threat Analysis Group, the tech giant’s team that monitors and works to thwart government-backed hacking against its 1 billion users worldwide.

Because of its vast user base, Google occupies a unique perch to track and analyze the digital aspects of the Ukraine war, which will mark its one-year anniversary on Feb. 24. The report also includes data from the threat intelligence firm Mandiant, acquired by Google Cloud in September, and Google Trust & Safety.

According to the report, the thousands of digital attacks that Google observed are part of an overall Russian assault that has seen “a multi-pronged effort to gain a decisive wartime advantage in cyberspace, often with mixed results,” as well as a plethora of information operations seeking to shape public perception of the war.

Shane Huntley, senior director of Google’s Threat Analysis Group, said the report attempts to both gather and contextualize “a pretty broad range of activities,” while being realistic and not overstating the impact of the cyber activities. “There is significant activity happening here,” he said, noting a “constant barrage of attacks on all fronts, but that doesn’t mean there is a significant success, or they’ve had any great, critical wins.”

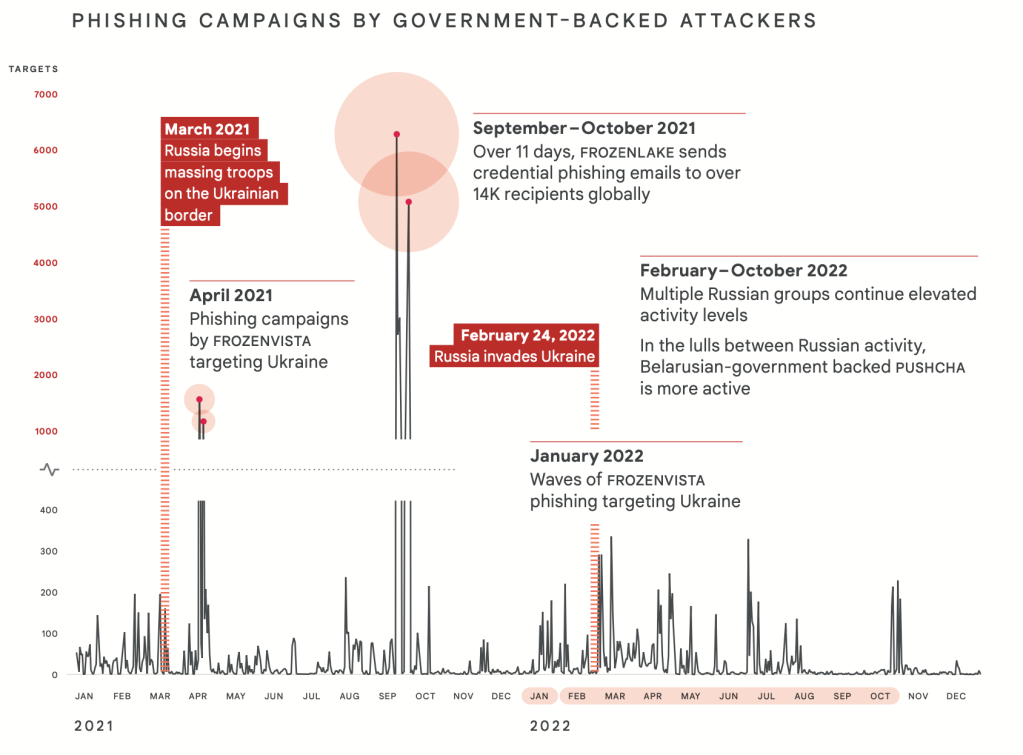

Still, the number of attempted cyberattacks has skyrocketed, according to Google. Russian phishing campaigns directed against NATO countries jumped by more than 300% over the last year, alongside a 250% increase in phishing campaigns against Ukrainian targets and more destructive malware attacks in the first four months of 2022 than the previous eight years.

The report offers new details on the range of cyberattacks, how they were deployed, and who may have been behind them. From the phishing attacks to information and influence operations to the affect on the global cybercrime ecosystem, the one-year mark created a natural point to reflect, said Huntley.

“There’s a lot of people thinking and theorizing about what cyberattacks look like in a time of war,” he said. “And now probably this is the best example we have of a major cyber power engaged in a kinetic war, and some real visibility of how, at least in this case, it was used. There will be lessons that we should learn here for future conflicts that can really shape the debate.”

Huntley noted that there are things that aren’t publicly known yet, and key questions remain unanswered. As an example, he said it’s not clear how integrated and coordinated Russian cyber operations are with the kinetic military operations. “Is it really well coordinated, or are they mostly operating independently? Because there’s some hints of that,” he said.

The documented activity is quite extensive, though. For instance, the report lays out how over the course of 2021 Russian-aligned hacking groups targeted Ukraine and targets in other countries with extensive phishing campaigns. One group Google calls Frozen Vista — also known as UNC2589, SaintBear, Nascent Ursa or UAC-0056 by the Ukrainians — sent more than 14,000 credential phishing emails to targets around the world in an 11-day period spanning September and October 2021. During lulls in Russian phishing efforts between February 2022 and October 2022, a group known as Pushcha — sometimes called UNC1151 and linked to Belarus by Mandiant in November 2021 and linked to the prolific Ghostwriter information operation — became more active, Google said.

Some Russian hacking groups “intensified” their ongoing attacks on Ukraine over the course of 2022, while others, such as ColdRiver, shifted their focus toward Ukraine. “While we see Russian government-backed attackers focus heavily on Ukrainian government and military entities, the campaigns we disrupted also show a strong targeting focus on critical infrastructure, utilities and public services, and the media and information space,” the report reads.

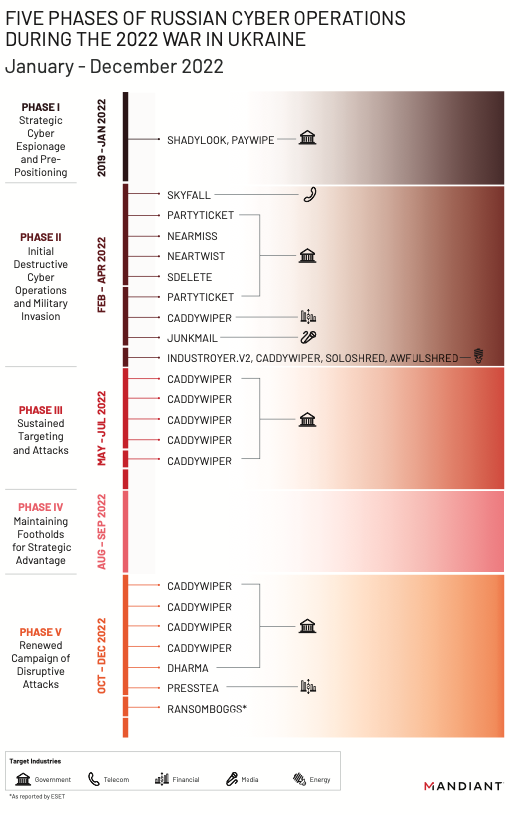

Russian hackers have a years-long history of targeting Ukraine with destructive malware, the report noted, including the 2017 NotPetya attack that caused an estimated $10 billion in damages globally. That history prompted many to fear a similar spillover problem with the war, but that “largely did not happen in 2022,” the report states. Nevertheless, “Mandiant observed more destructive cyberattacks in Ukraine during the first four months of 2022 than in the previous eight years with attacks peaking around the start of the invasion,” according to the report.

Mandiant observed at least six unique wipers, some of which had multiple variants, according to the report, but the lasting impact was limited. “While the destructive cyberattacks did achieve significant widespread disruption initially in some Ukrainian networks, they were likely not as impactful as previous Russian cyberattacks in Ukraine,” the report read. “To conduct the initial waves of destructive activity, Russian actors often employed accesses gained months before, which were often lost as the attack was remediated.”

Other companies, such as SentinelLabs and ESET, have published their own analyses of the wiper variants and attacks.

The past year has seen a wave of Russian information operations, as well, including efforts to shape opinion abroad while also targeting domestic Russian audiences to bolster and maintain support for the war, according to the report. Google disrupted more than 1,950 instances of Russian information operation activity on its platforms in 2022, the report read. The information operations related to the war includes a surge of activity from self-declared hacktivists — some authentic, others cutouts for government activity or working in support of Russian government priorities. These groups, such as KillNet, XakNet, engage in ongoing distributed denial of service attacks in Ukraine, the U.S. and NATO countries, and have also performed data leaks, Google said.

The war has also tested the loyalties of financially motived cyber criminals, the report notes, with some declaring political allegiance to Russian goals and others proclaiming neutrality. Perhaps the most prominent example came the day after the invasion when the notorious Conti ransomware crew declared loyalty to Russia and vowed to attack its enemies. A Ukrainian IT researcher with access to Conti servers struck back, leaking troves of Conti internal chats and materials, hobbling the group.

Fears of ransomware attack against the U.S. and NATO countries in response to Russian sanctions and other support for Ukraine were “largely unrealized,” the researchers noted. But tactics traditionally linked to financially motivated groups have become increasingly common in government attacks, the researchers said. “This overlap of activity is likely to continue throughout the conflict,” the report read.

Overall, Huntley said, there’s been a ramp-up of cyber hostilities between Russia and the West, which is something to keep an eye on as the war continues to play out. “Depending on how this war evolves, and how much Russia wants to lash out at NATO or other allies, that’s something to watch out for,” he said. “It’s more likely in the short term that this cyber activity is going to spill out more broadly than say kinetic activity or military activity is going to spill out for fairly obvious reasons.”