Hidden Mac malware designed to spy on ‘everyday people’

A unique Mac malware family that allows for a hacker to remotely spy on a targeted computer and install additional malicious software has been infecting U.S.-based machines for more than five years, according to Patrick Wardle, director of research with vulnerability testing firm Synack.

The actor responsible for the malware, dubbed FruitFly, is believed to be an individual hacker who has over the years continuously updated and improved a distinctive suite of hacking tools tailored for breaking into Apple computers. Based on a forensic analysis of the malware, it’s likely that the hacker is not financially motivated or connected to a foreign intelligence service, said Wardle, a former NSA staffer.

“This looks like a single attacker. And based on the malware’s capabilities, it seems like they did some pretty pervasive and intrusive stuff,” Wardle said. “The way the malware works it’s just not very scalable, this isn’t how an APT would do things. And this isn’t cybercrime.”

“From what I can see, it appears like FruitFly is being used to spy on everyday people,” said Wardle.

The initial infection vector for FruitFly remains unclear. Wardle said it’s likely either an infected website delivering the malware, or it comes from phishing emails or a booby-trapped application.

FruitFly “variant A” was first discovered by MalwareBytes researcher Thomas Reed in January.

More than 200 computers remain infected with the malware, said Wardle, who contacted law enforcement while researching FruitFly “variant B.” Wardle is currently preparing a presentation on the topic for the 2017 Black Hat USA cybersecurity conference. He provided CyberScoop with a preview of his upcoming research exhibition.

Wardle said that there’s likely more than two variants of FruitFly out in the wild, meaning that the number of infection could be much greater than 200. Apple issued a software update for Mac computers in January that patched many of the software vulnerabilities being exploited by FruitFly. But unpatched computers could still be infected.

More questions than answers

Wardle said that computers infected with FruitFly, which “called back” to the hacker’s infrastructure, varied in location and ownership — a clear targeting profile was not explicit based on associated victim information. Infected machines included both family and business computers, which further obfuscated the hacker’s underlying motive, Wardle said.

The researcher was able to study FruitFly by registering a backup command and control server that was once used by the hacker but which had recently expired in registration. By doing so, Wardle was able to test a copy of the malware in a closed environment to fully understand all of its qualities.

FruitFly was built in part with outdated functions and other computer code that dates back to as far as 1998. The author relied on “ancient functions,” MalwareBytes described, Perl programming language and open source libjpeg code, which was last updated in 1998. In addition, a comment in one file makes references to a version change that happened in order to bypass security measures pushed by Apple’s OSX Yosemite, which the tech giant released in 2014.

Experts describe FruitFly as a stealthy and reliable spying tool that was used only in a limited function. Until recently, very few people knew it existed, said Wardle.

“FruitFly is basically super-targeted malware that flew under the radar for a while. That’s how you write and use good malware so that it doesn’t get detected,” Wardle said. “I wouldn’t call it sophisticated, but it’s definitely feature complete … for example, if you look at FruitFly’s persistence mechanism at boot, it’s not very sneaky or particularly complex.”

Reed separately came to the same conclusion in a January blog post describing the mysterious Mac malware.

“Ironically, despite the age and sophistication of this malware, it uses the same old unsophisticated technique for persistence that so many other pieces of Mac malware do: a hidden file and a launch agent. This makes it easy to spot, given any reason to look at the infected machine closely (such as unusual network traffic),” wrote Reed. “The only reason I can think of that this malware hasn’t been spotted before now is that it is being used in very tightly targeted attacks, limiting its exposure.”

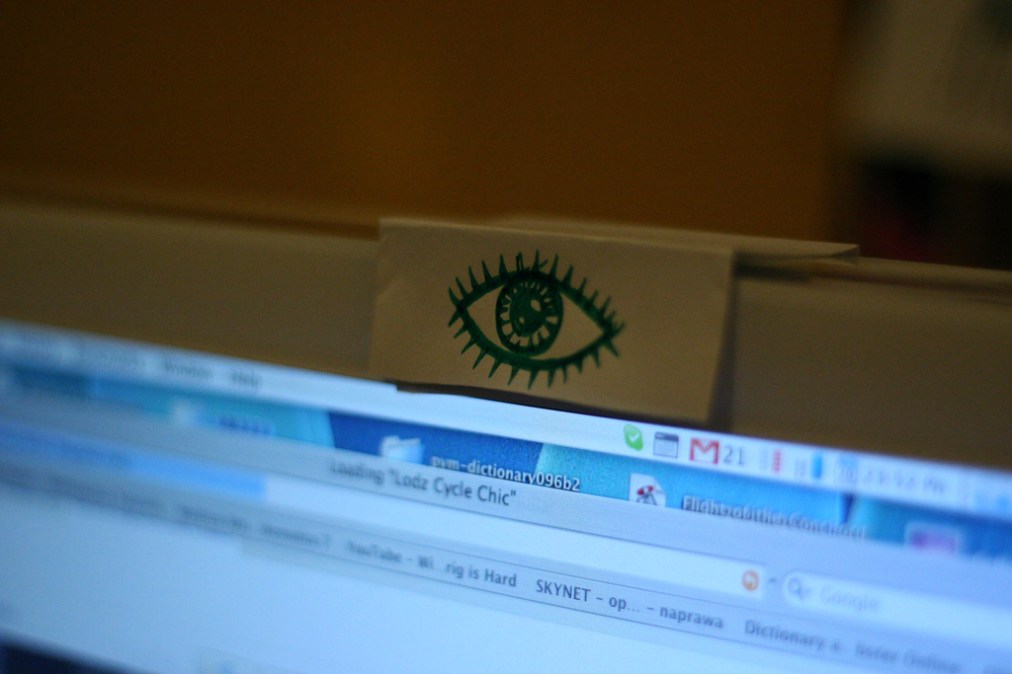

Once installed onto a computer, FruitFly gives the operator the covert ability to control a device’s mouse and keyboard; other capabilities, like a keylogger or access to a web camera could be easily added based on how the malware was designed, Wardle said. Variant A is already equipped with the webcam spying feature.

Run-of-the-mill features, like screen capture, the ability to kill a process, read a file or execute shell commands, also comes standard with FruitFly. Additionally, variant B of FruitFly offers an automated alert system which will notify the hacker when a user is active on their machine. This notification element, Wardle said, is an especially rare trait.

“As far as I know, I haven’t seen [this notification capability] in macOS malware before,” Wardle said. Why the capability was originally engineered into FruitFly remains unclear, but Wardle hypothesizes that it could be used to avoid a situation where the targeted individual sees that their mouse pointer is moving independently across the screen.

“Taking control of a mouse lets you interact with the UI really easily. It could maybe be used to turn off anti-virus or something like that, but in truth all those commands could be done with a keyboard,” he said.” So it’s possible there’s another reason to it.”