DOJ official: Whether they’re extradited or not, indicting foreign hackers is important

Even if foreign government hackers never see the inside of a U.S. courtroom, bringing criminal charges against them is still a key prong in American deterrence policy, a top Department of Justice official said Thursday.

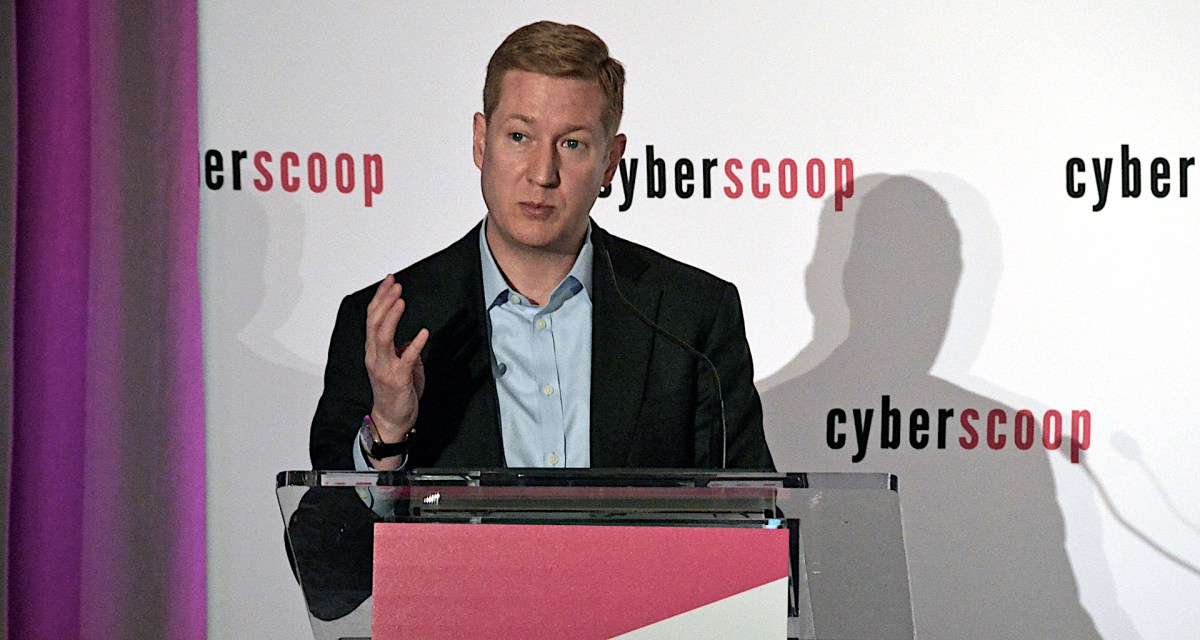

“Imagine a world … in which there are no criminal charges” and the private sector is left to levy the allegations themselves, Deputy Assistant Attorney General Adam Hickey said at the CyberNext conference in Washington, D.C. “What message does that send to a foreign hacker or the government he works for?”

In a series of cases in which nation-state hackers charged by DOJ remain at large, “all of those charges served a greater purpose” beyond apprehending the alleged perpetrators, Hickey said. The indictments have enabled other U.S. responses such as sanctions as well as joining with allies to call out state-sponsored hacking, he said.

Hickey spoke hours after the DOJ announced criminal charges against seven Russian military intelligence officers for hacking anti-doping and chemical-testing and anti-proliferation organizations. Three of those GRU officers were also charged by the DOJ in July for hacking into the Democratic National Committee and the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee during the 2016 presidential campaign.

Hickey disputed arguments that such indictments are a largely symbolic expense of law enforcement resources.

“It’s probably easy to forget … that until relatively recently, such charges were unheard of because we viewed the problem of foreign-state sponsored hacking through the lens of intelligence collection alone without regard to disruption and deterrence,” Hickey said.

Under President Barack Obama, the DOJ in 2014 brought the first U.S. charges of nation-state cyber-espionage with the indictment of five Chinese military officers. The policy of aggressively pursuing criminal cases against foreign government hackers has continued under President Donald Trump.

Some of the charged foreign defendants have been arrested. One example cited by Hickey was the case of Karim Baratov, a hacker who allegedly broke into 11,000 email accounts at the behest of Russian intelligence agency FSB. Baratov was arrested in Canada in March 2017 and has since been sentenced to five years in prison. Other defendants, however, probably would be much harder to apprehend, such as those who work directly for an agency like GRU.

The United States does not have an active extradition treaty with Russia. U.S. law enforcement officials generally have to rely on indicted Russian hackers traveling to a country that does have a treaty with the U.S. to have a chance of apprehending them. Such was the case when Yevgeniy Nikulin was extradited from the Czech Republic this year to face charges for hacking LinkedIn and Dropbox in a U.S. District Court in San Francisco.