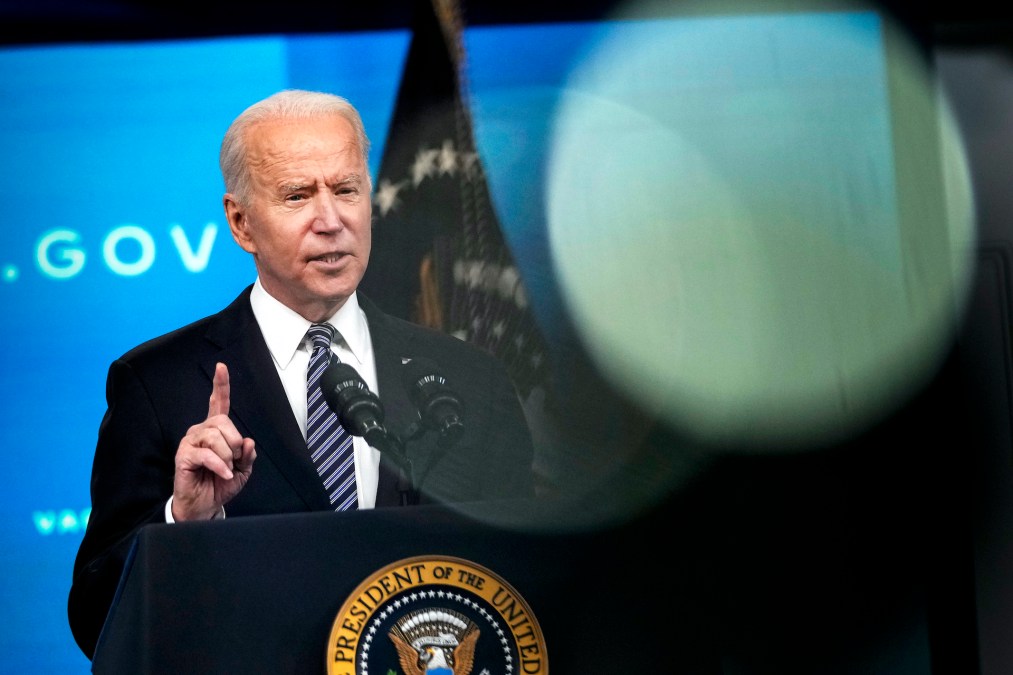

The big cyber issues Joe Biden will face his first day in office

Joe Biden has his work cut out for him.

Biden will be sworn into office on Jan. 20 with a long list of challenges ranging from the coronavirus pandemic to re-considering America’s place on the world stage. There’s also the fallout from a far-reaching hacking campaign that the U.S. has suggested is the work of the Russian government.

Yet the next American president has also chosen top advisers, including his picks to lead the Department of Homeland Security and the CIA, who appear to view digital security as an integral part of policymaking. Their thinking on these issues, and whether they succeed or fail in the face of deep-seated challenges to internet security, could affect the trajectory of Biden’s presidency.

Here’s a closer look at three of the more pressing cybersecurity challenges the administration will encounter.

Cleaning up the SolarWinds mess, then getting proactive

Biden has vowed to get to the bottom of the hack, in which suspected Russian operatives infiltrated unclassified networks at multiple federal agencies focused on national security, including the departments of Commerce and Justice. Ensuring the attackers have been evicted, then rebuilding networks where necessary, will be a laborious process for government IT security teams.

It’s a key task, though, meant to secure U.S. communications after one of the most significant breaches in recent memory.

“We, for some time now, are going to have to assume in government and [in many private-sector organizations] that the adversary is in our system,” Suzanne Spaulding, a former DHS undersecretary in the Obama administration, said Jan. 12 at a George Washington University event.

Ridding the attackers from networks is one thing; not letting the crisis go to waste and making tangible progress on supply chain security is another.

The alleged Russian spying operation, which uses tampered software made by contractor SolarWinds, revealed just how thoroughly a motivated and skilled attacker could compromise software development processes. While the Trump administration had multiple supply chain security initiatives, the SolarWinds hacking campaign will demand a fresh look at the problem.

The Biden team plans to do just that, according to a person familiar with the incoming administration, though what exactly those plans are remains unclear. There are already requirements in place for firms that do business with the Pentagon, like SolarWinds, to maintain a basic level of cybersecurity.

But that apparently did nothing to limit the impact of the breaches, and federal agencies could face pressure from lawmakers and the Biden administration to more closely scrutinize the security of contractors.

How Biden chooses to respond to Russia, if the U.S. formally concludes Moscow is responsible for the SolarWinds breaches, could shape the first year of the new administration’s cybersecurity work.

“I’m not going to telegraph our punches, but the president-elect has said that he will impose substantial costs for attacks like this,” Jake Sullivan, Biden’s national security adviser, told CNN this month.

Balancing defense with offense

Classified documents leaked by former U.S. intelligence contractors showed the commitment at the U.S. National Security Agency, CIA and elsewhere to conducting offensive cyber-operations. Meanwhile, critics say civilian agencies need more resources to protect their own networks, even as the Pentagon spends billions on computer network defense.

The Biden administration will have to make hard choices about whether the government will continue or deviate from the Trump administration’s apparent eagerness to use offensive cyber-operations. Either way, there is a broad consensus among U.S. lawmakers and former officials that more needs to be invested in defense.

DHS’s Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, which carved out an influential role for itself in the Trump administration, is the lead for defending federal agencies outside of the Pentagon from hackers. CISA is barely two years-old and had some 2,150 employees (not all of whom work on cybersecurity) in the 2020 fiscal year and a budget of $2 billion. (DHS as a whole employed some 240,000 people and commanded a budget of $88 billion in fiscal 2020.)

Biden’s advisers are keen on obtaining more resources for CISA, and giving the agency a greater role in cyber-defense, according to two people familiar with the incoming administration’s thinking. Some of the ideas floated in the transition team are having CISA use new cloud security services to defend other agencies’ networks, or do more to tap existing authorities to vet technology on those networks. The $1.9 trillion COVID-19 relief package that Biden is seeking from Congress includes an additional $690 million for CISA to boost agencies’ cyber-defenses and pilot a “new shared security and cloud computing service,” the Biden transition team said in a press release.

The incoming Biden administration’s focus on CISA is reflected in the fact that, according to acting CISA director Brandon Wales, the agency had briefed the Biden team roughly 20 times as of Jan. 8. Wales, who will stay on in the new administration, albeit not as CISA’s leader, has also said that the agency needs a better view of how other agencies’ deploy cloud computing to avoid another SolarWinds-type incident.

If CISA is granted greater authority and more resources, pressure will be on the agency to live up to its lofty mantra of being “the nation’s risk adviser.”

Curbing disruptive hacking

Totally preventing digital espionage is a fool’s errand; spies will spy.

But cyberattacks that destroy equipment — like North Korea’s alleged 2014 hack of Sony Pictures — or disrupt the global economy — like Russia’s alleged NotPetya assault in 2017 — are the kind of transgressions that the U.S. and its allies have sought to make taboo on the world stage. (The Stuxnet attack against Iran, which damaged centrifuge equipment more than a decade ago, has been widely attributed to the U.S. and Israel.)

A key piece of that diplomacy campaign is the idea of a cybersecurity coordinator position at the State Department focused on hashing out acceptable behavior in cyberspace. The Trump administration disbanded that position in 2018.

U.S. cybersecurity diplomacy has continued, though critics say the axing of the coordinator signaled to allies and adversaries that diplomacy in cyberspace was not a priority. The Biden team is planning to reinstate the cybersecurity coordinator at the State Department, a person familiar with the incoming administration said.

There are signs the Biden camp wants to go further in delineating what is acceptable to the U.S., and what isn’t, in cyberspace. One idea under consideration: a framework for responding to cyberattacks that makes clear that the U.S. will respond quickly and proportionately to major hacks.

It remains to be seen whether, in pushing for clearer rules in cyberspace, the U.S. does more to acknowledge its own formidable hacking tools. The NotPetya outbreak, after all, used a tool known as EternalBlue that unidentified attackers reportedly stole from the NSA.

The very definition of what’s acceptable remains in flux. Microsoft President Brad Smith, for instance, has suggested that the SolarWinds compromise was “not espionage as usual.” But the extent to which the Biden White House, now that it is in charge of elite U.S. hacking tools, agrees is another question.