Prolific Russian ransomware operator living in California enjoys rare leniency awaiting trial

Authorities and threat intelligence analysts alike relish taking ransomware operators off the board. Holding cybercriminals accountable through arrest, imprisonment, or genuine reform creates a powerful deterrent and advances the ultimate goal of a safer internet for everyone.

Getting to that point is a remarkably tough task for defenders. Ransomware attacks are often initiated by people living in countries that aren’t bound by extradition treaties with the United States or don’t cooperate with international law enforcement. When those obstructions aren’t in place, authorities can amass resources to hunt down those responsible for cyberattacks and bring them to justice.

The fight against cybercrime is grueling, and wins don’t typically countervail the losses. For nearly a decade, police have often made high-profile announcements about arresting cybercriminals, keeping them in custody until their court dates and seizing their ill-gotten gains. These acts send a clear message to the public and potential offenders that cybercrime is a serious offense, and authorities are taking swift, visible measures to uphold the law.

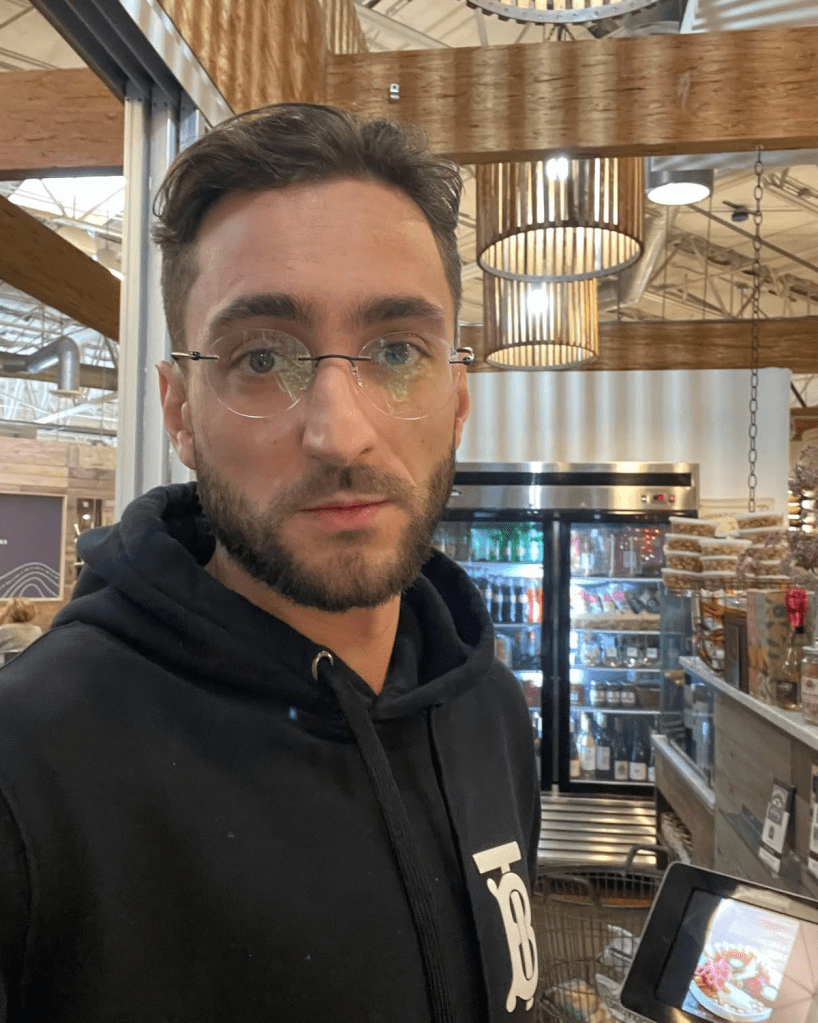

Ianis Aleksandrovich Antropenko exemplifies the profile of a modern cybercriminal, yet, unlike many others who have faced strict prosecution for similar offenses, the Justice Department has granted him liberties rarely extended to such suspects.

The 36-year-old Russian national was arrested almost a year ago in California for his alleged involvement in multiple ransomware attacks from at least May 2018 to August 2022. Yet, he was released on bail the day of his arrest and continues to live with few restrictions in Southern California awaiting trial for multiple felonies.

Antropenko is charged with conspiracy to commit computer fraud and abuse, computer fraud and abuse, and conspiracy to commit money laundering. He is accused of using Zeppelin ransomware to attack multiple people, businesses and organizations globally, including victims based in the U.S.

Antropenko pleaded not guilty to the charges in October.

The Justice Department recently announced it seized more than $2.8 million in cryptocurrency, nearly $71,000 in cash and two luxury vehicles from Antropenko in February 2024. His alleged crimes were publicly revealed for the first time last month when authorities unsealed various court documents.

Antropenko’s arrest and pending trial marks another potential win against ransomware, but many experts told CyberScoop they are stunned he remains free on bail. This rare flash of deferment in a case involving a prolific alleged cybercriminal is even more shocking considering his multiple run-ins with police since his 2024 arrest.

Antropenko violated conditions for his pretrial release at least three times in a four-month period this year, including two arrests in California involving dangerous behavior while under the influence of drugs and alcohol. Authorities haven’t explained why Antropenko was released pending trial, nor why parole officers and a judge repeatedly allowed him to remain out of jail following these infractions.

“On average, most ransomware actors, if they are brought into custody, are remanded because of a flight risk,” said Cynthia Kaiser, senior vice president of the ransomware research center at Halcyon.

“It’s rare to have a ransomware actor in U.S. custody,” the former deputy assistant director at the FBI Cyber Division told CyberScoop. “Typically, if the FBI believes that the person is a flight risk it would make the case for bond to be denied.”

Prosecutors in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Texas did not flag Antropenko as a flight risk in this case.

In the past year, other alleged ransomware suspects or cybercriminals — Noah Urban, Cameron Wagenius, Connor Moucka and Artem Stryzhak among them — were all detained pending trial. Urban, who was sentenced last month to 10 years in prison, and Wagenius, who has pleaded guilty to some charges, were arrested in the United States. Moucka and Stryzhak were arrested elsewhere and extradited to the U.S.

Pretrial treatment of cybercrime suspects hasn’t always adhered to strict norms, especially when the accused’s mental health status was taken into account. Paige Thompson, who was arrested in July 2019 for hacking and stealing data from Capital One and dozens of other organizations for a cryptocurrency mining scheme, was deemed a “serious flight risk” by prosecutors, but still released pending trial four months later.

A U.S. district judge in Seattle determined Thompson didn’t pose a threat to the community and previously told attorneys he was “very concerned” that Thompson would not receive adequate mental health treatment from the Bureau of Prisons.

Thompson was found guilty of multiple counts and sentenced in October 2022 to time served and five years of probation, much to the chagrin of prosecutors. A federal appeals court overruled the district court judge’s sentence earlier this year, calling the punishment “substantially unreasonable.”

Yevgeniy Nikulin, a Russian national arrested in October 2016 on charges related to breaching a database containing 117 million passwords from LinkedIn, Dropbox and other services, was extradited to the U.S. from the Czech Republic in 2018 and ruled fit to stand trial, despite exhibiting mental illness symptoms throughout his incarceration and trial. He was detained pending trial and sentenced to 88 months in prison in September 2020.

Notwithstanding these variances in previous cases, some experts are struck by other irregularities in Antropenko’s case, including his conditions of release. He is not banned from using the internet or computers, but limited to devices and services disclosed during supervision that are subject to monitoring.

More lenient conditions of release are typically offered in exchange for cooperation, according to threat analysts and a former FBI special agent who specialized in cybersecurity investigations.

“The investigators that tracked him down will certainly want to know who the bigger fish are, and they’ll want to figure out who else they could take down,” the former FBI special agent, speaking on condition of anonymity, told CyberScoop. “If he’s willing to cooperate, then normally the federal system will do good things for you.”

Authorities imposed travel restrictions on Antropenko, required him to surrender his passport, banned him from entering a Russian embassy or consulate and are monitoring his location.

Bad behavior going back years

The federal case against Antropenko accentuates how finite resources can put law enforcement and federal investigators at a disadvantage as they confront a constant crush of cybercrime.

The FBI and prosecutors accuse Antropenko of deploying ransomware and extorting victims by email, and implicate him and his ex-wife, Valeriia Bednarchik, in the laundering of ransomware proceeds. Investigators traced the path of ransom payments, money laundering techniques and services, and determined the seized accounts, cash and vehicles were derived from criminal proceeds.

The FBI said it found at least 48 cryptocurrency addresses referenced in Antropenko’s email account — china.helper@aol.com, which he registered in May 2018 — including “emails that received or negotiated ransom payments” and emails about other ransomware attacks.

A cluster of Bitcoin addresses owned by Antropenko “had received a total of approximately 101 Bitcoin” as of Feb. 5, 2024. Out of this amount, 64.6 Bitcoin was sent to the cryptocurrency mixing service ChipMixer, according to the FBI. As of today’s rates, the current value of 101 Bitcoin is almost $10.9 million.

The 2023 takedown of ChipMixer, which was used by criminals to launder more than $3 billion in cryptocurrency starting in 2017, provided crucial evidence for this investigation, according to Ian Gray, VP of intelligence at Flashpoint.

“Only after law enforcement seized ChipMixer’s infrastructure could investigators trace the funds linked to accounts registered in Antropenko’s name,” he said. “The sophistication of Bitcoin tracing and clustering techniques also likely contributed to the timing, as law enforcement has adopted software and tools more widely.”

Prosecutors allege that Antropenko and Bednarchik funneled money from computer fraud victims through ChipMixer, then back to their own exchange accounts. Antropenko also allegedly arranged in-person cryptocurrency-to-cash swaps in the U.S., depositing the cash in small sums under $10,000 into his bank account.

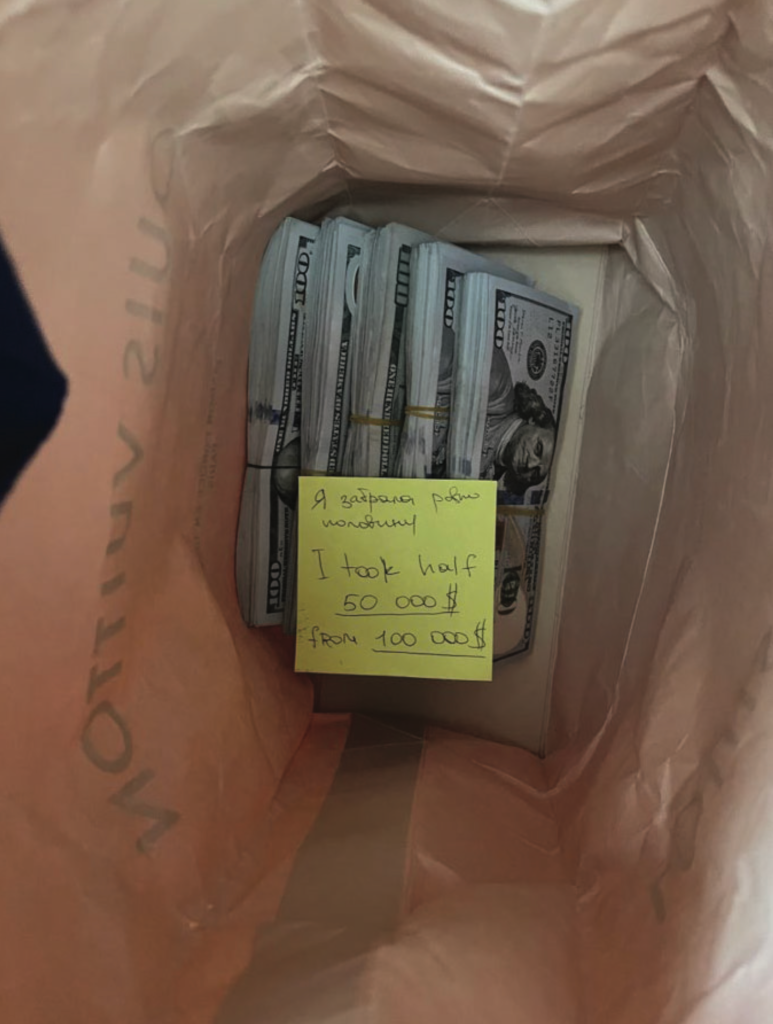

FBI investigators traced Antropenko’s activities via accounts he held at Proton Mail, PayPal and Bank of America, and accounts he and Bednarchik controlled at Binance and Apple. In Bednarchik’s iCloud account, agents found a seed phrase for a crypto wallet that had received over 40 Bitcoin from Antropenko’s accounts, as well as evidence she had agreed to safeguard a disguised copy of this phrase so the funds could be accessed if Antropenko became unavailable. Her account also contained joint tax returns with Antropenko and photos showing large amounts of U.S. cash.

Authorities also seized cash and two luxury vehicles from the apartment Antropenko and Bednarchik once shared in Irvine, Calif. This included a Lexus LX 570 that Antropenko purchased for more than $123,000 in November 2022 and a 2022 BMW X6M that Antropenko and Bednarchik purchased for $150,000 in cash in November 2021. Photos of vehicles matching those descriptions are depicted on Antropenko’s public Instagram account.

Ransomware operators have been assisted by their spouses in other cases, but their partners’ involvement is typically limited to money laundering, Allan Liska, threat intelligence analyst at Recorded Future, told CyberScoop.

While many ransomware operators and affiliates operate outside of Russia now, it is rare for a Russian national to live in the U.S. while initiating ransomware attacks for as long as Antropenko allegedly did, Liska said.

“It sounds like he may have had additional information about other people, maybe bigger fish that law enforcement could go after,” he said.

The U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Texas declined to answer questions or provide additional information. The most recent attorney on record for Antropenko did not respond to a request for comment.

Antropenko didn’t just inflict damages on his cybercrime victims, as alleged by prosecutors. His volatility erupted around those closest to him, according to Bednarchik, who accused him of domestic violence in temporary restraining orders she filed against Antropenko in April and May 2022.

Bednarchik has been identified as Antropenko’s unnamed co-conspirator through court documents and public records. While authorities said they plan to bring charges against her, no cases are currently pending.

In court filings, Bednarchik painted a picture of a controlling relationship, writing that Antropenko “constantly threatens me with full custody of our son, because he has a lot of money” and expressing fears he might take their child to Russia without permission.

Court records reveal the family lived together in Miami and later Irvine until 2022. Despite Bednarchik reporting only $800 monthly income from her clothing business, she estimated Antropenko earned $50,000 per month from “cryptocurrency dividends,” describing him as “the breadwinner for the family.”

When Antropenko was arrested in September 2024, Bednarchik posted his $10,000 bail, identifying herself in the affidavit as his ex-wife.

“She’s either being redacted because she’s a victim or because she is collaborating with law enforcement and has been able to get her name redacted,” Zach Edwards, senior threat analyst at Silent Push, told CyberScoop.

Antropenko’s ties to Zeppelin ransomware

Authorities did not describe the extent to which Antropenko was involved with Zeppelin ransomware. Prosecutors mention unnamed co-conspirators in some court documents, indicating they are investigating or aware of others involved in the ransomware-as-a-service operation.

The Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency said Zeppelin ransomware victims include a wide range of businesses and critical infrastructure organizations, including defense contractors, educational institutions, manufacturers, technology companies and organizations in the health care and medical industries.

Zeppelin, a variant of the Delphi-based Vega malware, was used from at least 2019 to mid-2022, the agency said in an August 2022 advisory. A ransom note included in CISA’s advisory listed an AOL address for communication regarding extortion payments.

Prosecutors and investigators working on Antropenko’s case said Zeppelin ransomware affected about 138 U.S. victims since March 2020, including a data analysis company and its CEO based in the Dallas region where Antropenko faces federal charges.

Prosecutors have consistently declared the case against Antropenko “complex,” with evidence surpassing 7 terabytes of data, including personally identifiable information of victims, such as names, addresses, photos and bank account numbers.

Zeppelin and Antropenko’s alleged activities rose during the second wave of ransomware, when many cybercriminals were winging it and law enforcement activity was at a lull, Liska said. “If you start off with a mistake, that mistake is going to catch up to you,” he said.

Indeed, threat researchers and analysts attribute Antropenko’s capture to “sloppy” behaviors and practices, including his use of major U.S. service providers.

“Antropenko’s operational security was remarkably poor,” Gray said.

“He used a personal PayPal account linked to recovery emails for ransomware operations, shared usernames between banking and ransomware accounts, and stored sensitive information like cryptocurrency seed phrases and photos of large cash amounts in iCloud accounts,” he continued. “These OPSEC failures ultimately led to law enforcement identifying Antropenko.”

Pretrial release violations

While prosecutors push Antropenko’s trial date further down the road — currently set for Feb. 6, 2026 — his personal life has been unraveling. He was hospitalized on a mental health hold on Dec. 31, 2024, and spent a week in a behavioral health hospital, according to a pretrial release violation report.

Antropenko told his probation officer that his ex-wife took his son from him unexpectedly, which led to a significant bout of depression and increase in alcohol consumption. “While walking around his RV park intoxicated, he was approached by an individual who offered him an unknown drug,” which he assumed was some type of methamphetamine, Antropenko’s probation officer wrote in the court filing.

Antropenko said he had little recollection of the events that followed. Once he was placed in a police car after law enforcement arrived the following morning, “he assumed he was being arrested which exacerbated his depression, prompting him to bang his head on the window of the police car, after which he recalls regaining consciousness in the hospital,” the probation officer said. No charges were filed.

Almost two months later, Antropenko was arrested for public intoxication in Riverside County, Calif., when he was found laying unresponsive in the center divider of a roadway. Antropenko told his probation officer he sat down on a curb near his home to smoke a cigarette after consuming four to five beers and was feeling tired, so he fell asleep. He was released the following day.

A U.S. magistrate judge in Texas allowed Antropenko to remain out on bond and modified the conditions of his release to include a ban on alcohol consumption and submit to regular alcohol testing.

“It strikes me as unusual to have so many drug violations and stay out on bail,” Kaiser said. “It would be overly lenient if they were still perpetrating crimes obviously against others. It appears he’s harming himself.”

In April, Antropenko contacted his parole officer to make an unsolicited admission to cocaine use, according to a court document filed in May. “The defendant stated that he attended a birthday celebration for a friend’s sister. When he went to the restroom some ‘random people’ offered him a ‘bump of cocaine,’” his probation officer said. The court took no further action.

“Even if he is a cooperating witness, he has been given a lot of freedom, a lot more freedom than we normally see in this case,” Liska said. “I can’t think of any case, of anybody this high profile, that has been given this level of freedom, cooperating or not.”

Edwards is also dismayed Antropenko remains out on bail pending trial.

“It’s wild that a citizen from Russia who has been accused of partnering with serious global threat actors and is out on bail for leading a ransomware campaign, has been arrested multiple times for issues associated with alcohol, including passing out on a street in public, and also admitted to using cocaine while out on bail, and yet his bail hasn’t been revoked,” he said.

Former law enforcement officials were less shocked about the circumstances of Antropenko’s case than security analysts.

Adam Marrè, chief information security officer at Arctic Wolf, said the post-arrest privileges granted to Antropenko aren’t that odd, especially since Antropenko’s alleged pretrial release violations don’t have anything to do with cybercrime.

Marrè said Antropenko’s alleged violations would have frustrated him when he was a special agent at the FBI investigating cybercrime, but he understands the court’s decisions, adding “people are innocent until proven guilty.”

It’s important to note the FBI is focused on outcomes, according to Kaiser. “Getting money back to victims who were stolen from is more important than punishing some guy, especially if he’s not doing [ransomware] activities anymore,” she said.

“It’s hard to arrest these people in the first place and stop them, which means it’s very complicated to deter them over a long period of time,” Kaiser added. “There’s no one arrest that’s going to stop these types of activities.”