Under tough surveillance, China’s cybercriminals find creative ways to chat

Think of it as hiding in plain sight.

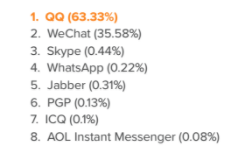

Ninety-nine percent of Chinese cybercriminals communicate over instant messenger apps like QQ and WeChat, according to research from the cybersecurity firm Flashpoint. Both apps are wildly popular in China and almost nowhere else. The apps, which are both owned and operated by the multibillion-dollar Chinese tech giant Tencent, cooperate directly and extensively with expansive government censorship and surveillance.

To the outside, it would seem to be a barren and dangerous environment for coordinating criminal enterprises. That doesn’t stop the hackers, though.

“You would imagine that people who are engaging in illicit activities would at least make an effort to use a platform that’s not explicitly monitored by the regime, right?” says Jon Condra, Flashpoint’s Director of East Asian Research and Analysis.

To beat government surveillance, China’s underground cybercriminals deploy technical, typographic and linguistic tricks that can make tracking them increasingly difficult. In Russia, by stark contrast, Jabber reigns as the messenger supreme in the cutting-edge cybercriminal underground in large part because it’s so resilient against the prying eyes of government surveillance. But in China, where the number of netizens is approaching 1 billion, the criminals are able to blend into the crowd in order to thrive and profit even on instant messengers that hand over everything to Beijing.

How the Chinese cybercriminal economy communicates. Source: Flashpoint

Given the massive and unparalleled size of the Chinese internet, many users simply calculate that being caught would be akin to winning some sort of terrible lottery. In a country with more than 1.4 billion people, at least half are now online. Even the vast resources of the Chinese surveillance regime make that a dauntingly large target.

At just under 1 billion users on QQ and WeChat combined, even Tencent itself ends up automating much of its surveillance and censorship tools. One advantage the cybercriminals have is that the authorities tend to prioritize dissident and political chatter far above the cybercriminal underground, Condra explained.

The 99 percent of Chinese cybercriminals who communicate over QQ and WeChat employ a handful of tricks to beat those tools.

For advertising their wares, they rely largely on images instead of plain text because it’s a much more difficult job for authorities to detect, read and analyze text inside images.

Another common trick is spacing out characters, Condra says.

“Chinese words can either be single character, dual character or multi-character. The way it works is you can string characters together that make sense until you come up with a word. What they’ll do, even in a one-character word, is put one character, an emoji, another character, an emoji, another character and so on,” Condra says. “They break it up. Whatever filters Tencent is using to flag illicit words probably aren’t going to catch that.”

The criminals also mix English and Chinese inside posts and even inside single phrases, Flashpoint says. One example seen commonly in the wild is the various mixings of “bank 卡” or “銀行 card.” Hackers will also mix in pinyin, the romanization of the written Chinese language, to further obfuscate their messages.

Further down the rabbit hole, criminals use numerical slang that is even more difficult to figure out. On the simple end, sounding out the numbers in Chinese sounds something like another Chinese word or phrase.

The word for database is 數據庫 (Shùjùkù, with kù meaning repository). In criminal chat groups, Flashpoint says, you might see someone refer to 褲子 (Kùzi). It’s slightly different but is recognized to be referring to databases. The word 信封 (xìnfēng which translates to envelope) actually means a full set of leaked account credentials. Words take on new meanings so that even a native Chinese-speaking human tasked with surveilling these communities will have difficulty parsing what’s being said. Automated surveillance has an even tougher time, Flashpoint says.

But chat rooms and forums do get shut down, strongly suggesting that dedicated human investigators are active at certain periods. At the end of 2015, China passed a new national cybersecurity law igniting anti-cybercrime action across the major platforms that resulted in a cascade of forums and chat groups go down. Imminent changes to internet security legislation this summer are expected to trigger another wave of turbulence on the Chinese underground.

Furthering the difficulty of surveillance and law enforcement is the lucrative underground market for stolen QQ accounts, which require a phone number and name to register. A lot of QQ accounts are compromised by malware that is then deployed for illegal purposes.

One major reason Chinese cybercriminals still use tools like QQ and WeChat are because they generally lack other options. The software adopted by criminals elsewhere is often blocked with unprecedented efficiency by Chinese censors from both the government and the private companies who take their cue from Beijing. Given a choice, the Chinese might opt for other methods of communication. They generally don’t have that choice.

“The Chinese [hackers] have a unique problem,” Condra says. “A lot of the services they’d like to use are probably blocked from being downloaded or even running probably. Even if they had the impetus to move to something like that, adoption would be a problem because they’re not given access to those types of thing.”

Tor, for instance, is an anonymity network popular in the rest of the world for many different kinds of users, including cybercriminals. It’s far more difficult to use inside China, however, due to government meddling. More sophisticated users can safely get on Tor while the rest turn to more easily accessible services — even if they’re being watched by authorities.