West Africa’s Scattered Canary gang shows how cybercriminals supersize email scams

Sometimes the most effective scam techniques are also the most mundane.

Business email compromise attacks don’t involve advanced malware, and aren’t carried out by headline-grabbing nation-state hackers. BEC scams simply rely on personalized emails to dupe victims into transferring funds to someone who appears to be a co-worker, friend, or family member.

But this fraud technique is taking a toll, depriving Americans of a vast sum of money each year. In 2018, the FBI’s cybercrime center received over 20,000 BEC complaints that accounted for estimated losses of $1.2 billion. Understanding the scale of the problem requires understanding how perpetrators scale their operations.

The decade-long evolution of one Western African cybercriminal gang is a case in point. Email security firm Agari on Wednesday published research documenting the so-called Scattered Canary group’s rise from a lone individual to dozens of operatives specializing in various aspects of fraud. The group also has grown from peddling romance scams to targeting big corporations with email schemes.

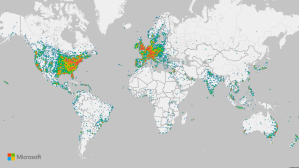

After honing their skills, in March 2017, two of Scattered Canary’s original members turned to phishing for enterprise credentials by spoofing Adobe, DocuSign, and OneDrive applications, according to the research. From then until November 2018, the group almost exclusively targeted businesses in the U.S. and Canada, netting over 3,000 account credentials through phishing.

Today, at any given time, the group might be involved in several different types of scams, from tax and Social Security fraud, to employment rackets, Agari said. “[L]ike entrepreneurs in any industry, cybercriminal organizations work to achieve growth by developing and validating scalable business models across a diversified set of revenue streams,” the Agari report says.

The group now uses more than two dozen message templates against targets, including documents that appear to be direct deposit and W-2 forms.

Crane Hassold, senior director of threat research at Agari’s Cyber Intelligence Division, said Scattered Canary uses an organizational model that is common with other criminal gangs.

“Most West African cybercriminal groups we track are organized in a similar hierarchy to Scattered Canary,” Hassold, a former FBI analyst, told CyberScoop. “Much like a business, these groups grow over time as their profits increase.”

Compared to blocking malware-based intrusion attempts, defending against BEC scams requires an approach that analyzes the relationship between the sender and receiver of an email, Hassold said.

“Historically, email defenses have revolved around things like attachment and content analysis, which works well for more technically sophisticated attacks [like malicious payloads], but are not ideal for detecting [BEC] attacks that are not technically sophisticated and do not contain content that is overtly malicious,” he added.

Above all, it is a lucrative business for cybercriminals that is not going away. And companies entrusted with handling classified contractors have also found themselves in the crosshairs. Last year, email scammers stole more than $150,000 from two cleared defense contractors and a university, according to the FBI.

“BEC can no longer be seen in isolation and thus unrelated to other email deployed criminal enterprises,” the Agari research concludes. “Instead, we must view it as part of a larger ecosystem of cybercrime, with BEC as its current apex.”