Verkada breach spotlights ongoing concerns over surveillance firms’ security

Even for Elisa Costante, who studies vulnerabilities in surveillance devices for a living, the breach at the security-camera startup Verkada was startling.

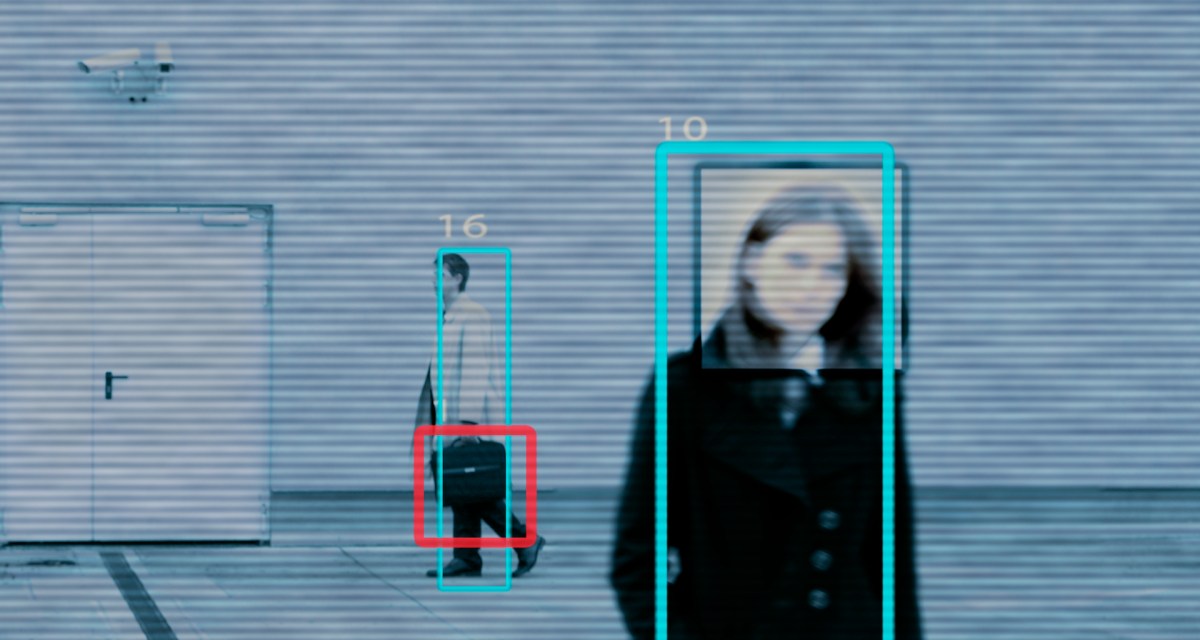

A group of hackers earlier this month claimed to have access to some 150,000 live-camera feeds that Verkada maintains in schools, prisons and hospitals. The incident provided outsiders with an entry into live video feeds at companies including Tesla, and enabled hackers to access archived video from Verkada subscribers.

“It really opens the eyes on what can happen” when an attacker exploits access to a web of insecure surveillance devices, said Costante, a senior director at security vendor Forescout Technologies.

The U.S. Department of Justice on Thursday announced an indictment against Tillie Kottman, one of the people who claimed responsibility for the incident, for alleged computer and wire fraud, and aggravated identity theft. The charges don’t mention the Verkada breach, and accuse Kottmann, who lives in Switzerland, and others of hacking dozens of companies and government organizations since 2019. Kottmann declined to comment on the charges.

Verkada claims to have clients in the Fortune 500, but the San Mateo-based company’s customers represent a mere fraction of the multibillion-dollar market for internet-connected surveillance cameras. The breach, experts say, peeled back the curtain on a world of private surveillance that is invasive and ripe for further exploitation by malicious actors.

Kottman told Bloomberg News that they were motivated to expose the scope of private surveillance practices. But some security analysts like Costante worry that attackers with different motivations could be much more disruptive to an organization.

Internet-connected cameras “are a great candidate for initial access” to a computer network that an attacker can use to pivot to other devices on that network, Costante said. Concerned that it was an overlooked field of security research, Costante and her colleagues in 2019 demonstrated how to exploit weak protocols used by cameras to intercept data and replace camera footage with their own.

A disruptive hack on security cameras isn’t just theoretical. A Romanian woman admitted to using ransomware to shut down police cameras used by the Washington, D.C., police department just days before the 2017 U.S. presidential inauguration.

Sen. Ron Wyden, D-Ore., who has pushed for legislation to make firms more accountable for the data they collect, said he agreed that the Verkada breach is but a window into a much larger security issue.

“Pervasive surveillance — whether of our phones, our movements or where we go online — creates huge new threats to Americans’ security,” Wyden told CyberScoop. “Hacks like [the Verkada incident] expose the threat that surveillance by the government and private companies alike will be turned against law-abiding Americans by criminals, predators and spies.”

Cities like London, New York and Singapore are now strewn with surveillance cameras whose cybersecurity is sometimes an afterthought. London had one surveillance camera for every 15 residents, according to one study published last year, making it one of the most surveilled cities in the world.

There also are some indications that there would be more known compromises if security personnel had more visibility. In a 2018 report, a British watchdog warned that the “risk potential for intrusion” by state or individual actors into the country’s reams of surveillance cameras had “significantly increased.” (The watchdog credited U.K. cybersecurity standards for beginning to address that risk in subsequent reports.)

Growing legal battles over private surveillance

Any such cybersecurity regulation, at least on a national level, has been elusive in the U.S. In that absence, consumers and rights groups have increasingly brought lawsuits against corporations to accuse them of being careless with consumer data.

The most prominent recent examples of that in the private surveillance world are multiple lawsuits brought by rights groups against Clearview AI, the data-scraping facial recognition firm whose customer list was hacked.

It’s unclear what legal exposure, if any, Verkada has after its breach. Kottmann, one of the alleged hackers, said they found a user name and password for a Verkada account administrator publicly exposed to the internet. Verkada CEO Filip Kaliszan apologized for the firm’s security shortcomings on March 12, adding that he had “redirected our engineering team to make security, trust and privacy, their number one priority.”

Jeffrey Vagle, an assistant professor at Georgia State University College of Law who focuses on privacy, said one of the main enforcement tools for better security practices in the U.S. right now are investigations by the Federal Trade Commission. The FTC could, in theory, level fines on a firm like Verkada were it to find that its cybersecurity practices were “unfair” or its advertisements of secure products were “deceptive,” Vagle said.

Jerry Flanagan, director of litigation at the nonprofit Consumer Watchdog, said the swell of class-action lawsuits against breached companies is “a barometer, to some extent, of the consumer outrage about the practice.”

“I worry, though, about a lack of awareness about the newest technologies,” Flanagan said, referring to the type of facial recognition techniques employed by companies like Verkada.