What actually happens when a company examines third-party risk

For a moment, look past Russian cybercriminals, North Korean cryptocurrency scams and the idea that election infrastructure used by democracies around the world lacks meaningful digital safeguards.

While those issues are significant, people in charge of information security at large U.S. companies spend the majority of their time assessing whether their firm is likely to experience a data breach that begins outside of their own proprietary network.

That assessment goes beyond the deluge of obfuscated code, technical jargon or marketing pitches. It’s rooted in crunching numbers in Excel spreadsheets and other measuring strategies that can quantify whether their partners and vendors are prepared to keep hackers out.

Security bosses at Fortune 500 companies traditionally have compelled partners to answer monotonous questionnaires about their cyber readiness. Private sector surveys, including some obtained by CyberScoop, typically include hundreds, and sometimes thousands, of arcane questions meant to elicit information about how firms use encryption, require authentication and otherwise protect sensitive data.

Some of the questionnaires, which in some cases cost money to complete, are years-old and have been administered in different areas of the private sector on an annual basis. One checklist, known as the Standardized Information Gathering (SIG) questionnaire, has been used throughout the financial industry.

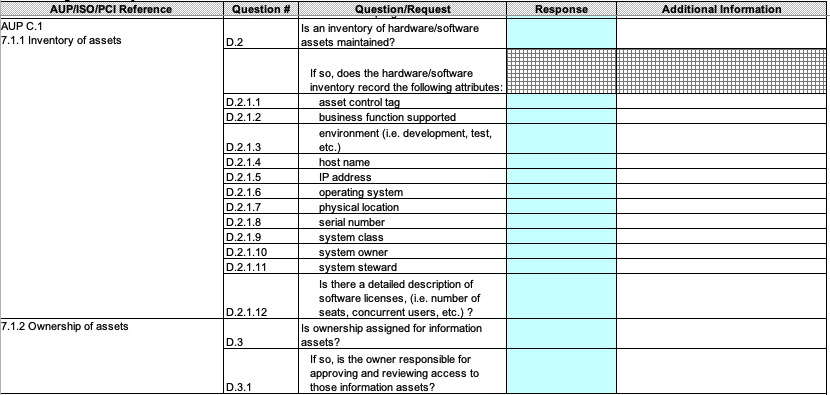

The questionnaire itself contains a number of distinct surveys, seeking information on topics including asset management, organizational security and human resources security. All told, the file contains 1,215 questions. While security leaders likely don’t need an answer to every question, many ask for a level of detail that could require numerous employees to work on the answers full-time.

In this screenshot of the SIG third party risk questionnaire, respondents are asked to provide details about their asset inventory protocols.

In another section, the SIG document asks recipients if their company has an employee termination policy and, if so, whether the human resources department notifies the security team in order to revoke access to corporate information.

Some industries now are moving toward a “shared assessment” questionnaire methodology. With that strategy, a company answers one questionnaire about their data protection strategies, and the results are shared throughout the wider industry. That way a single company only needs to go through the process once, rather than dedicating a team of employees to work full-time on answering these surveys, a mind-numbingly dull task that can take hours to complete.

“We’re starting to see in the marketplace a shift to consortium assessments,” said T.R. Kane, a partner in the cybersecurity practice at PricewaterhouseCoopers, where his team conducted 7,000 assessments on clients’ behalf last year. “We’re seeing a lot of this in financial services, where they’re getting together and saying, ‘We have the same types of suppliers and vendors and we’re asking them the same things 90 percent of the time’ … so vendors are looking to streamline this process.”

One shared assessment, the Exostar questionnaire, is popular among U.S. defense contractors trying to secure their supply chain. The checklist asks respondents to answer a series of detailed questions, many of which seek to understand the extent to which the company has followed the National Institute of Standards and Technology’s 800-171 guidance for unclassified information technology.

Sample questions found elsewhere include the following:

-

Do all devices that store or process sensitive information at a minimum have all unnecessary ports and services disabled and the device is used for limited functions (ex. A device acting solely as a file server vs. a file server, FTP server, and web server)?

-

Do all devices that store or process sensitive information at a minimum have patches deployed for high risk operating system and third-party application vulnerabilities within industry best practices i.e. 48 hours) and medium/low risk patches to be deployed in [less than] 30 days?

-

Does your company perform cyber security audients by objective internal employees or external 3rd parties on IT systems/devices and IT services that store or process sensitive information at least annually?

“You’re looking for discrepancies. You say, ‘You’ve got a great patching program, but when I look at your web servers there are issues there that I can observe,’” said Kevin Gallagher, managing director for risk and financial advisory at Deloitte.

“A thorough assessment is a minimum eight week process from when you first reach out to company through the end. A lot of that depends on how much depth you want to get into but a full validation can be a lengthy process.”

From Spreadsheets to Scorecards

For a generation, survey questions like this have provided the most meaningful insight into third-party security habits. But CISOs are moving to an assessment model that requires vendors and corporate partners to verify their practices work as intended. Any company can claim it protects information, but they are increasingly being asked to put their money where their mouth is.

The product tests come after a number of high-profile breaches, like the 2013 Target breach and the incident last year at MyHeritage, occurred because hackers gained a foothold in one company and used it to infiltrate a more valuable target.

“The tailored questionnaire is very off-putting because it requires a lot of attention from their IT and security teams,” said Dane Sandersen, global security and infrastructure director at bicycle-maker Trek, which has hired consultants to administer questionnaires, and also uses custom surveys. “We still do that assessment, but the universal acceptance and the actual audit you get from [other services] are much easier, and it gives me more confidence.”

More businesses are probing their counterparts from the outside by hiring firms like BitSight, SecurityScorecard and Accenture Security to administer the security equivalent of a pop quiz. By considering publicly accessible factors such as whether a partner has patched known vulnerabilities, or if their data is for sale on cybercriminal forums, information security leaders can reasonably determine if a partner is taking steps to prevent data breaches.

“What’s on my mind is how assessments are moving from an event basis, like when we buy something where we go interrogate clients, toward a more pervasive monitoring model,” said Brent Maher, CISO at Johnson Financial Group. “When I’m talking to other CISOs from small, medium, or large companies, everybody is moving in the same direction.”

Wisconsin-based Johnson has used SecurityScorecard for two years in order to gauge the way partners protect information. SecurityScorecard assembles a risk score for every company it tracks, based on factors including DNS security, endpoint protection, patching policies, business reputation, social engineering tests and data loss prevention, among others.

As measuring risk becomes a business model, companies whose revenue comes from being part of the supply chain now know business partners are watching them closer than ever before.

“One of the most critical business dynamics that’s taken place over the past five years is businesses holding each other accountable for cybersecurity,” said Jacob Olcott, vice president at BitSight. “Market participants are holding each other accountable but, my god, have you ever tried to figure out a questionnaire? It’s completely subjective, so in an ideal world it would be a combination of security ratings plus the results of assessments or documentation.”

The scorecard model seems to be having a positive effect. Johnson Financial works with two vendors, a financial technology company with roughly 10,000 employees and an email filtering company about half that size, that dramatically have improved their scores over the past two years, Maher said. Maher suggested the upgrades were the result of peer pressure exerted by other companies unwilling to assume risk from the fintech and email firms.

“Patching cadence and network security typically were issues with those two,” he said. “As more customers started to track them, we’ve noticed the scores go from a low C or D to a strong B or an A.”