Russian hackers targeted internet routers worldwide in apparent spy campaign, say U.S. and U.K.

Hackers backed by the Russian government carried out a coordinated campaign against internet traffic routers used in small offices and residences worldwide, cybersecurity officials from the U.S. and U.K. said Monday.

The hackers targeted network infrastructure in the public and private sectors with the potential goals of espionage and the theft of intellectual property, the officials from the White House, Department of Homeland Security, FBI and Britain’s National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) told reporters.

It’s the first time U.S. and British governments have issued such a joint alert. The announcement comes as Western countries continue to sound the alarm about Russian cyber-aggression. The U.S. sanctioned several Russian oligarchs earlier this month in part because of that country’s malicious actions in cyberspace.

The alert was pre-planned and the U.S. and U.K. have been coordinating its release for a long time, the officials said. NCSC head Ciaran Martin said that the British agency has been tracking the hacking campaign for about a year, and the groups behind the campaign for longer than that.

Organizations targeted in the hacking campaign included government and private sector organizations, critical infrastructure owners and operators, and internet service providers supporting those sectors, the officials said.

No zero-days needed

The U.S. government received information from multiple sources since 2015 indicating that Russian hackers are exploiting such routers, according to a joint report released the U.S. Computer Emergency Readiness Team (US-CERT) after the call.

The hackers don’t need to use zero-day vulnerabilities or install malware on the routers, the report says. Instead, they exploit devices with outdated, unencrypted protocols or unauthenticated services; misconfigured devices; and devices no longer receiving security patches from their manufacturers.

US-CERT says Russian hackers conducted “broad-scale and targeted scanning of Internet address spaces” to search for devices with such weaknesses. From there, they can use the discovered weak devices to extract information critical to the security of a network, such as vulnerable devices and login credentials.

The report also includes guidance on how network operators can mitigate some of the weaknesses agencies identified.

The officials did not specify how U.S. or U.K. agencies have responded to the hacking campaign, but White House Cybersecurity Coordinator Rob Joyce said that “when we see malicious cyber-activity, whether it be from the Kremlin or other nation-state actors, we’re going to push back.”

Joyce said that the campaign is not an isolated incident and should be viewed in context of past Russian cyberattacks. The goal of the hacking campaign, he said, is not necessarily to steal information from the penetrated networks. The intrusions could be leveraged for future operations.

“We can’t rule out the possibility that Russia may intend to use this set of compromises for future offensive cyber-operations as well. It provides basic infrastructure that they can launch from,” Joyce said.

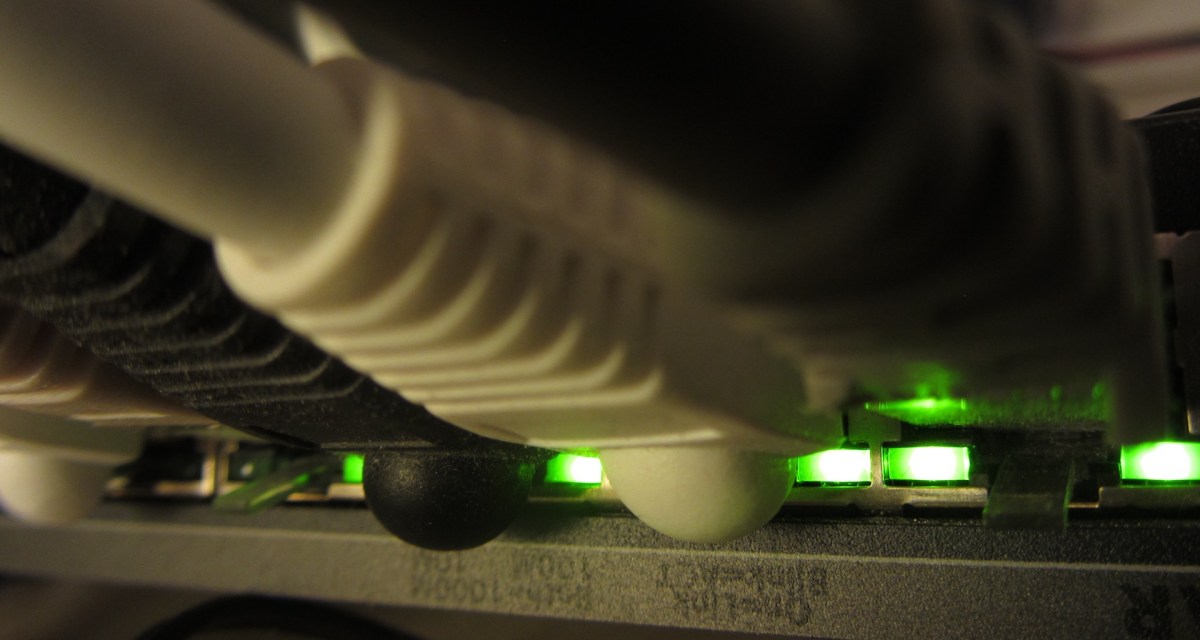

Officials said the affected hardware includes common routers used in small offices and home offices, known as SOHO routers, as well as residential routers.

“Most traffic within an an organization or between an organization and externally must traverse these types of devices. So when a malicious actor has access to them, they can monitor, modify, or deny traffic,” said Jeanette Manfra, a top cybersecurity official in DHS’s National Protection and Programs Directorate.

Martin said the U.K. corroborated the U.S.’s assessment of the campaign and confirmed that it affected the U.K.

“This is a significant moment in the transatlantic fight back against Russian aggression in cyberspace,” Martin said.