Why was North Korea running a phantom cybersecurity startup in Malaysia?

Cut off from the rest of the world, North Korea may be the last country anybody would expect to produce a cybersecurity startup advertising products intended to compete on the global market. North Korea’s leadership, however, often turns expectations upside down.

From the heart of the Malaysian capital of Kuala Lumpur as well as the nearby financial center of Singapore, North Korean spies covertly ran a technology business that, until last year, publicly sold a wide array of products including iPhone apps, web development apps and even cybersecurity tools. Virtually nobody knew who really controlled the company until recently. Even today, nobody is entirely sure how it worked.

Now, CyberScoop has learned that United Nations officials are currently looking into the business as part of larger inquiries into sanctions violations by North Korea.

The connection between Adnet and the network of front companies was first uncovered by Reuters journalists who, alongside U.N. officials, began last year looking into the individuals and entities connected to North Korean companies in Malaysia. Many of the companies were said to be directed by the Reconnaissance General Bureau (RGB), the North Korean intelligence agency responsible for clandestine operations and cyber activity. Over the course of the investigation and publication of the U.N. report, most of the companies stopped operations.

“The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea is flouting sanctions through trade in prohibited goods, with evasion techniques that are increasing in scale, scope and sophistication,” the report said. “The Panel investigated new interdictions, one of which highlighted the country’s ability to manufacture and trade in sophisticated and lucrative military technologies using overseas networks.”

Adnet was run by Kim Chang Hyok, also known as James Kim, a North Korean man who served as director and shareholder in five companies directly connected to North Korean intelligence, according to Malaysian business records, U.N. investigators and Malaysian as well as international media reports.

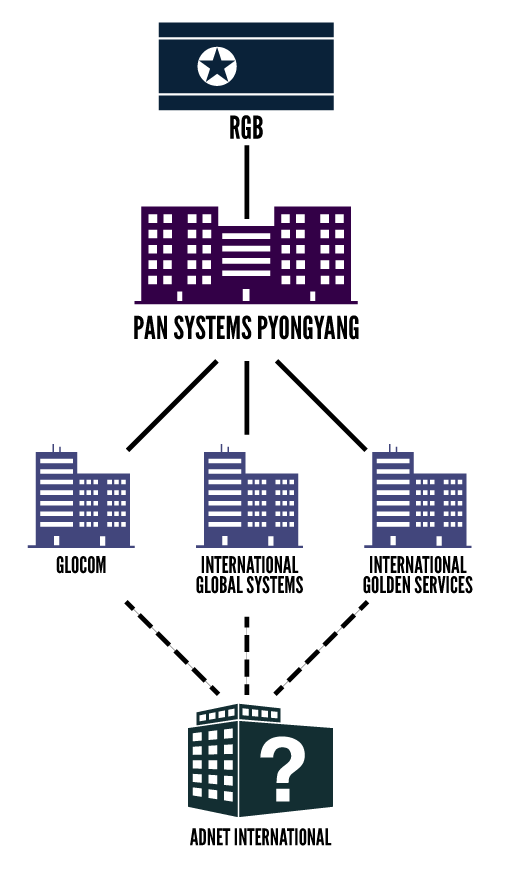

The exact connections between North Korea and Adnet are unknown. A parent company, Pan Systems Pyongyang, is controlled directly by the RGB, according to the U.N. report. The most widely known of the parent company’s subsidiaries is Glocom, which is accused of illegally selling millions of dollars worth of sophisticated battlefield radio equipment.

RGB’s Malaysian operations employ the same staff and use the same office space through a series of additional front companies. Adnet shared a Kuala Lumpur office (according to WHOIS data and the front company’s registered address) and North Korean personnel like Kim Chang Hyok with the other fronts. He took over 58 trips from North Korea to Malaysia since 2012 , according to the U.N. panel that authored the North Korea report, all of which are now the subject of further investigation. He has also met numerous times with Ryang Su Nyo, the director of Pan Systems Pyongyang, who was once caught attempting to smuggle $450,000 in cash out of Malaysia to North Korea. She is accused by the U.N. of being an RGB operative.

Because the exact nature of the connections between Adnet and Glocom remain unclear and are still under inquiry, Adnet was not specifically mentioned in the U.N. report. The U.N. investigators could not find a clear link between Adnet and the prohibited activities — arms trafficking and money laundering — that the other companies stand accused of. The U.N. investigation itself was conducted narrowly regarding the manufacture and sale of military communication hardware. Adnet only emerged in the periphery.

Meanwhile, North Korea’s cyber activity — with Adnet as one small piece in a larger puzzle — is attracting greater attention by the day.

A chart showing the connections between the North Korean government and Adnet International (Data: United Nations/ Graphic: Emma Whitehead/Scoop News Group)

Adnet was described on the company website as a “complex of research, production, sales and services to orders” with 500 employees. It boasted involvement in “world-level research in and development of information processing technology, software and hardware,” including “biometrics identification techniques based on fingerprint, palm-print or face identification skills, artificial intelligence techniques such as intelligent games and expert systems, and other IT fields.”

The website’s security section listed a range of products including fingerprint identification tokens, intrusion prevention systems, secure document protection systems, virtual private network clients and USB security keys.

“The fingerprint products based on self-developed fingerprint identification technique were awarded four golden prizes at Geneva International Invention Exhibitions held in Switzerland (1990~1996),” the website read. “We are on an advanced level in development of face and palm-print identification techniques.”

There is no record of such an award being won, no record of Adnet existing during that time period and no reason to take the website’s information at face value.

Adnet’s website was taken down earlier this year, which falls in line with how the network of front companies regularly shifts. The website still exists in caches on various search engines. Old firms are often erased and new ones created in what’s likely an attempt to stay below the radar. Of all the companies around in 2015, only Glocom, whose website is still up and running, seems to be outlasting the U.N. inquiry. It’s unclear if any newer companies exist.

While the overall investigation continues, flouting sanctions has allowed North Korea to access the international financial system while trading goods — including military products — at what appears to be exceptionally high profit rates, according to Reuters. While Glocom is getting the lion’s share of attention, Adnet remains shrouded in further questions. Sophisticated military hardware and ammunition makes for a much cleaner case than computer security products.

Datuk Mustapha Ya’akub, a prominent Malaysian politician in the country’s ruling Umno party, has admitted to setting up three companies, including Adnet, with North Korean nationals. He told local media that the companies, including Adnet, were shut down after warnings from Malaysian authorities and because there were no profits.

“We started the first company in 2005, and it was closed down because there were no returns, and in the end, all three companies were shut down,” Ya’akub said recently.

CyberScoop tried reaching out through multiple channels, but several phone numbers and email addresses associated with Adnet International are no longer functional. Inquiries to the contact information for the front companies remain unanswered.

Investigating the claims, local media interviewed several Malaysians who said they had worked with North Korean nationals to set up companies within Malaysia, an activity reportedly going on since at least 2005.

North Korea has sought to build its own computer technology industry since 1979. The 1980s saw the establishment of several technology-focused higher education institutions and, in 1986, the country hired 25 Soviet computer instructors to train “cyber-warriors,” according to South Korean intelligence. In the last decade, there’s been an intensification of that effort both within North Korea’s borders and in operations around the world. Cyberwar, alongside a strong nuclear deterrent, is viewed by the country’s leadership as a key weapon in North Korea’s struggles and potential future asymmetrical wars with South Korea and the United States.

The 69-year-old Kim dynasty dictatorship has been targeted extensively by U.S. cyberattacks that contradict the popular image of North Korea as a pre-internet oddity. The internet’s global expansion, even into North Korea, has been met with an increased arsenal of digital weapons at the Kims’ fingertips.

RGB is the agency, according to former Director of National Intelligence James Clapper, that is responsible for high-profile cyberattacks. From 2012 to 2014, North Korea’s Strategic Cyber Command nearly doubled in size to 5,900 agents, according to South Korean intelligence, with more than 1,000 of those individuals working overseas. That was the year the country attacked Sony Pictures, according to American intelligence, destroying 70 percent of the firm’s computers, leaking masses of internal data, getting high-powered Hollywood executives fired and prompting the unprecedented cancellation of the wide release of a film because it offended the Kim regime.

That same group has been accused of hacking world banking and stealing $81 million from Bangladesh bank reserves through SWIFT (the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication), a global payment network used between banks.

The U.N. panel asked the government of Malaysia whether it intended to expel Kim Chang Hyok and freeze the assets of the known front companies. They’ve received no answer yet.

Read the full U.N. report below:

[documentcloud url=”http://www.documentcloud.org/documents/3520438-NORTH-KOREA-REPORT.html” responsive=true sidebar=false text=false pdf=false]