Former top spy says U.S. not positioned to fight information wars in cyberspace

When U.S. officials realized last year that Russian intelligence services’ hacking into the IT systems of the Democratic National Committee was just one part of a full-featured information warfare operation, they faced a number of immediate problems, the nation’s former top spy said Wednesday.

James Clapper, who was director of national intelligence under President Barack Obama, said the first dilemma was well-understood: how to warn the American people about the Russian effort to meddle with the election without appearing to put a thumb on the scale of the presidential poll.

There was a second and much less well-understood problem, though: how to fight back.

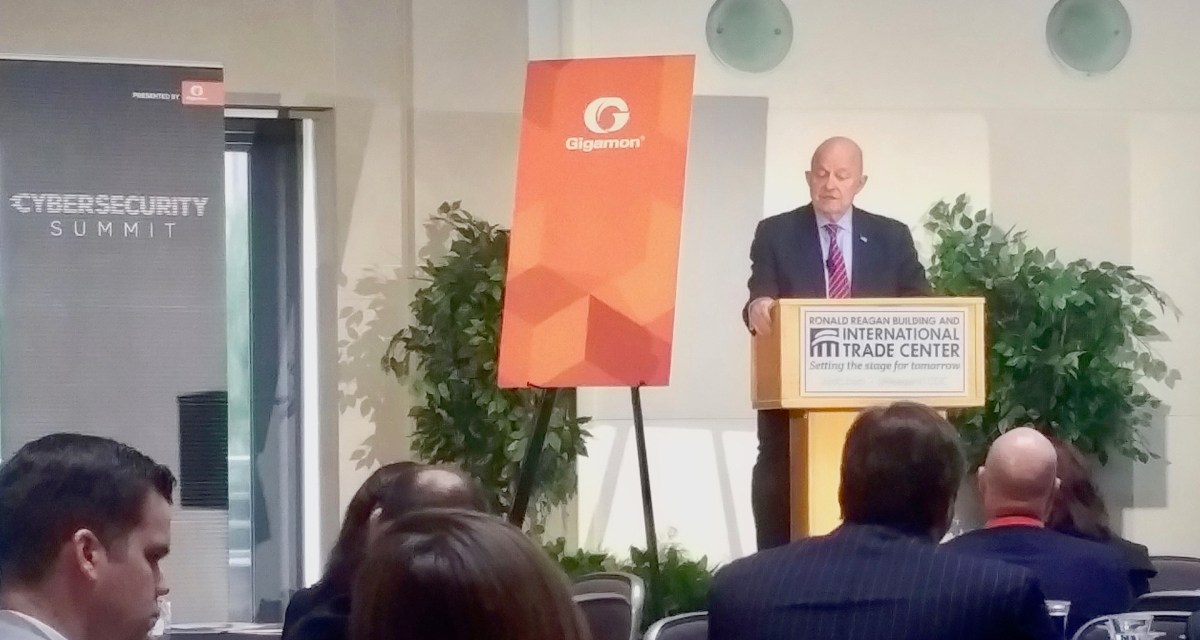

“We don’t really have a good way to respond” to the efforts like those aimed at Democratic candidate Hilary Clinton, Clapper said at Gigamon’s Public Sector Cybersecurity Summit.

The information warfare created not just fake news, but the real thing — like the stories that came out of the documents dumped from the DNC hack. Both kinds were then amplified them through automated social media bots and armies of paid Internet trolls.

Democracies, especially those with a built-in aversion to the use of state power in the information space, face a fundamental question when confronting such campaigns, Clapper explained: “Should we be engaging in counter-information warfare” at all?

Long-time observers of Russian military doctrine have labeled the effort to disrupt the election a form of “hybrid warfare” also known as “conflict short of war” and characterized by the use of deniable techniques like hacking and non-state actors as proxies or tools.

“The Russians are finding this a very effective tool,” Clapper said.

Clapper said his own view was “I don’t think that [any response] should be the role of the intelligence community.” The nation’s spy agencies were equipped to provide intelligence, to do the attribution of cyberattacks and place them in a strategic context to help policy makers understand the adversary’s intentions, he said. But beyond that, the decision about the response “is above my pay grade.”

“It’s a policy judgment — is the intelligence good enough and what do you do about it?” he said.

The United States needs a new agency, “a U.S. Information Agency on steroids … robustly staffed and financed, that once the intelligence community has detects what the adversary is doing” can move to counter it, he said.

The USIA — derided by critics as an American propaganda agency — was disbanded in 1999, after the end of the Cold War appeared to make its function obsolete.

Lawmakers attempted to revive or recreate it in a controversial law last year. Originally sponsored by Sens. Rob Portman, R-Ohio and Chris Murphy, D-Conn., S.2692, the Countering Information Warfare Act of 2016, was eventually signed into law as part of the National Defense Authorization Act. The law seeks to expand the remit of the State Department’s Global Engagement Center, which is currently charged with countering ISIS social media and online propaganda, into a generalized mission to counter “fake news” and other kinds of foreign misinformation.