How two researchers used an app store to demonstrate hacks on a factory

When malicious code spread through the networks of Rheinmetall Automotive last year, it disrupted the German manufacturing firm’s plants on two continents, temporarily costing up to $4 million each week.

The attacks were the latest reminder to factory owners that computer viruses can hobble production. While awareness of the threats has grown, there’s still a risk that too many organizations view such attacks as isolated incidents, rather than the work of a determined attacker that could be visited upon them.

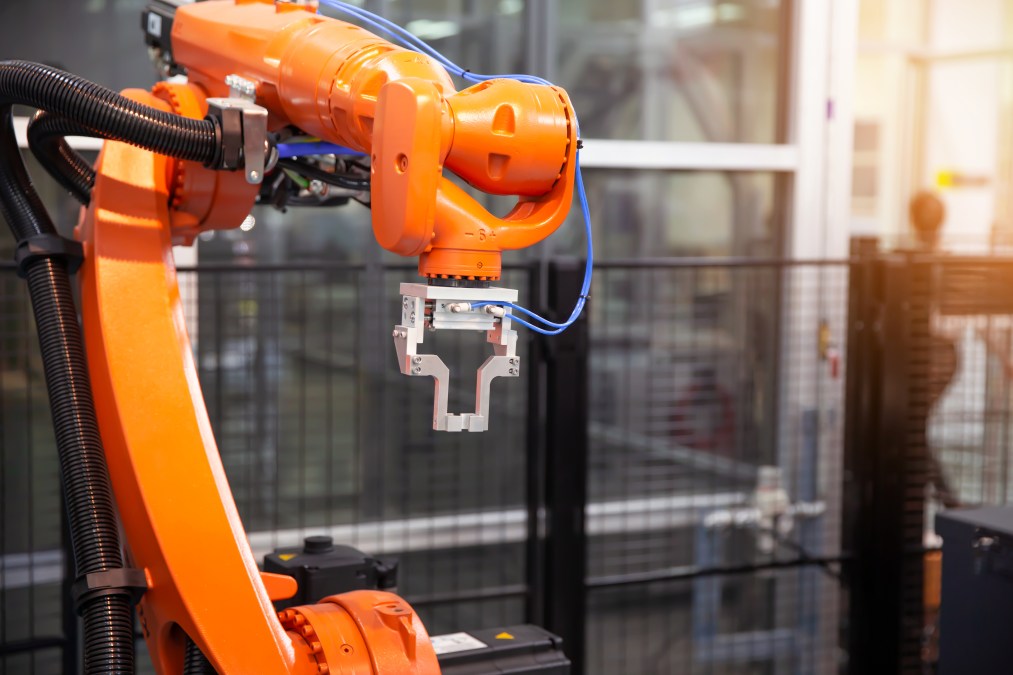

Federico Maggi, a senior researcher at cybersecurity company Trend Micro, set out to dispel that mindset. So he used a laboratory housed at Politecnico di Milano School of Management, Italy’s largest technical university, to show how attackers could disrupt production on the factory floor. His goal was to use the hypothetical hacks to help organizations address weaknesses in their defenses before actual attackers strike.

“We wanted to look for something different, something that future attackers may want to use,” Maggi told CyberScoop.

Maggi and Marcello Pogliani, a colleague from the university, produced a 60-page study detailing different ways of attacking a factory to make their point: It’s not about one vulnerability or one system. A determined hacker could have a range of options for slipping their disruptive code into a facility.

For instance, the researchers demonstrated a hack of machinery used to drill holes in toy cell phones, and showed how a supply-chain attack could distort temperature readings in the factory, bringing it to a halt. They used software libraries to deliver malware to factory devices that interact with those software tools.

Maggi started with a popular application marketplace maintained by Swiss industrial giant ABB that engineers use to upload programming code for factory robots. He found a vulnerability in the app store that let him upload his own code to the store. Once that code was installed at an engineering workstation on his factory floor, Maggi said, he was able to harvest data from the workstation.

“There was no sandboxing,” Maggi said. “We were able to read files, exfiltrate files from that machine just with a simple plugin.”

ABB ultimately fixed the vulnerability.

The research comes with important caveats: Maggi was not attacking a factory staffed with people who might be able to detect the attacks, which involved breaking into different machines in stages. And some of the attacks required access to a network to execute.

Evil twins

Maggi also took aim at the “digital twin,” a digitized replica of a factory machine or process that manufacturers use to test performance. He uncovered a flaw in software that manages digital twins and showed how an attacker might manipulate the code. The factory’s machinery could, in theory, be tricked into producing goods based on the faulty design.

The issue is larger than that. With mobile phone apps, for example, the Android or iPhone downloading them have a standard way of verifying that they’re legitimate and not pirated. But with digital twins, Maggi said, that’s not the case.

“There’s no standardized way to communicate and to transfer digital twins in a way that there is full integrity checks applied at every step,” he said.

His paper makes several security recommendations for mitigating the attacks, including validating software deployed on workstations. But some of the supply chain issues the paper raises will take longer to address.

With an array of vendors sometimes producing a single device used on a factory floor, U.S. manufacturers also are taking more steps to secure their supply chains through a federal program run by the National Institute of Technology and Standards.

The “complex software supply chain with [its] many dependencies,” was a motivating factor behind the project, Maggi wrote in his paper.