The thin line between saving a company and funding a crime

Ransomware negotiation is a dark but widely acknowledged reality in the cybersecurity industry — one that many argue is a necessary practice, even if it largely occurs out of sight. Brokering payments and terms with cybercriminals who hold organizations’ data and operations hostage places security professionals in a fraught position that requires them to balance a responsibility to meet their clients’ needs without fueling the spread of financially-motivated crime.

The pitfalls of ransomware negotiation are excessive — pinning the goals of cybercrime against victims and incident response firms that typically face no good options. Negotiators are charged with ensuring their clients don’t break any laws by financially supporting sanctioned criminals, but they also have to consider the lines they won’t cross without betraying their moral compass.

These backchannel negotiations can go awry for various reasons. Many people involved in ransomware negotiation prefer to share very little about what transpires in these discussions, a decision that ensures the terms of ransomware payments remain largely unscrutinized.

Yet, many security companies and professionals spoke to CyberScoop about the challenges and benefits of ransomware negotiation after two of their own became turncoats. The former incident responders, Ryan Clifford Goldberg and Kevin Tyler Martin, were moonlighting as ransomware operators and pleaded guilty last month to a series of ransomware attacks in 2023.

“There’s no structured community of practice, no peer review, and no recognized body to certify or hold negotiators accountable,” Jon DiMaggio, principal at XFIL Cyber, told CyberScoop. “It’s one of the few areas of cybersecurity with no real standards, an unregulated tradecraft that still operates like the Wild West.”

This uneven approach manifests across the landscape, particularly among the top incident response firms, which have varying levels of comfort with ransomware negotiations. CrowdStrike and Mandiant draw a firm line, refraining from providing ransomware negotiation services to clients.

If a client is considering paying a ransomware group, Mandiant will explain the options and let the client decide. The Google-owned company will also share what it knows about the group’s reputation for honoring terms and provide a list of third-party vendors that specialize in ransomware negotiation.

Adam Meyers, head of counter adversary operations at CrowdStrike, is firmly in the don’t-pay-ransoms camp. But he, too, recognizes it’s not always that simple.

“No good comes from paying them,” but sometimes in extreme cases when the choice is between a business’s downfall or potentially putting the people you serve at risk of significant harm, victims don’t have a choice but to pay the ransom, Meyers said.

Palo Alto Networks Unit 42 takes things to the finish line, but stops before payment. “The boundary for us is we don’t perform ransomware payments. That’s actually an intentional decision on our end to separate those out,” Steve Elovitz, vice president of consulting at Unit 42, told CyberScoop.

“We will perform negotiations when requested by our clients, but we will not perform the payments,” he added. “There’s the complexity side of it, but there’s also just the moral side of it — not wanting to be involved, really, in the transaction itself.”

The red lines in ransomware response — viewing stolen or illegal data on dark web forums, collecting that information, engaging with cybercriminals, negotiating and, ultimately, submitting payment — can push those involved beyond their comfort zones, said Sean Nikkel, lead cyber intelligence analyst at Bitdefender.

Lack of transparency engenders isolation

These self-imposed limits highlight how secretive ransomware negotiations tend to be, which creates a vacuum in which criminals thrive, DiMaggio said.

“The lack of transparency isolates everyone,” he said. “Victims don’t know what’s normal or fair, law enforcement is often left guessing, and the criminals use that silence to control the narrative and drive up their prices.”

Nikkel asserts some secrecy is necessary, yet ransomware negotiators are “operating without a license and it kind of freaks me out a little bit,” he said.

Professional certifications exist for many lines of intelligence work, but there’s nothing for ransomware negotiation, he added.

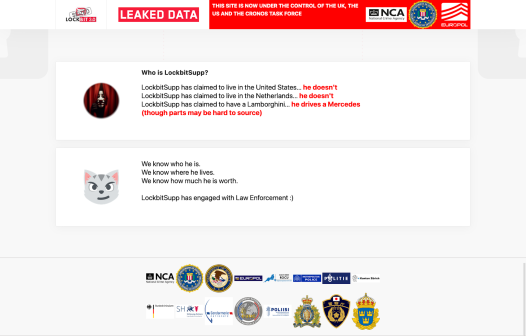

DiMaggio, who has infiltrated ransomware groups to investigate their operations, dox their leaders and chronicle stories that would otherwise go untold, said victim organizations constantly make the same mistakes because lessons from these attacks are rarely shared.

“Until the industry finds a responsible way to collect and analyze anonymized negotiation data, we’ll keep fighting each case in the dark,” he said. “Transparency isn’t about shaming victims — it’s about denying criminals the advantage of secrecy.”

Open sharing of ransomware negotiations is a non-starter for many important reasons, experts said. These communications contain privileged information that could tip attackers off to counterstrategies or empower them with information they can use as leverage to further compromise victims.

“It would be difficult to do that in a way that doesn’t compromise the practice,” said Kurtis Minder, the co-founder and former CEO of GroupSense who published a book in July about his experiences as a ransomware negotiator.

Cynthia Kaiser, who joined Halcyon’s ransomware research center as senior vice president after 20 years with the FBI, shares that view.

“You don’t want to do anything that re-victimizes the victim,” she said. “If that information goes out, that should be their choice.”

The “darkness” about negotiations doesn’t merit the same emphasis as the need to better understand “how insidious and gross all these ransomware attacks are, and who they’re attacking,” Kaiser added.

“That’s the only way we can really grapple with the actual extent of the threat, and that’s not happening right now,” she said. “That information doesn’t get out there enough.”

Key negotiation skills and considerations

Minder got pulled into his first ransomware negotiation in 2019 by accident and against his best intentions. “Somewhat reluctantly, I agreed to do more and then it sort of snowballed on us,” he said. “We didn’t really want to do this.”

Since then, Minder has been involved in hundreds of ransomware negotiations for major companies and small businesses who he volunteered to help in his personal time.

There is no litmus test for what makes a good negotiator, but soft skills and emotional intelligence are critical, he said.

“Empathy is one of the most important things,” Minder added. “Not sympathy — empathy — being able to effectively put yourself in the bad guys’ shoes is super powerful.”

As ransomware attacks have grown, so too has the mixed motivations of attackers attempting to extort victims for payment.

Attacker volatility has increased in the past four years and complicated the considerations negotiators must heed in their response, said Lizzie Cookson, senior director of incident response at Coveware by Veeam.

Some attackers are “eager to get paid, but they’re also in it for the notoriety, for the bragging rights, for the media attention,” said Cookson, who’s worked as ransomware negotiator for more than a decade. “That’s where we start to encounter more concerning behavior — more hostility, threat actors threatening violence, making threats against people’s family members.”

These cases, which occur much more often now, are more likely to result in broken promises — data leaks after a ransom was paid to avoid such an outcome or follow-on extortion demands, she said.

Indeed, cybercriminals consistently pull new threads to amplify the pressure they place on victims. This includes elements of physical extortion wherein ransomware groups call and threaten executives, claiming they know where the executives’ kids go to school, where they live and how they get to work, said Flashpoint CEO Josh Lefkowitz.

These threats put business leaders in precarious, unexpected positions that challenge their preconceived notions about how they’d respond to a cyberattack, Lefkowitz said.

Ransomware negotiation requires practitioners to navigate between doing what’s necessary and what’s right, DiMaggio said. “The key is to treat every negotiation as a crisis with human consequences, not just a transaction.”

Negotiators reflect on previous cases

Ransomware negotiators tend to run through common checklists based on patterns they’ve experienced, but each incident is unique and requires some level of improvisation.

Matt Dowling, senior director of digital forensic and incident response at Surefire Cyber, said ransomware operators, on the whole, are more trustworthy now than when he first got involved in negotiations in 2019. The practice, he said, has also improved because threat intelligence is more useful, making negotiations a data- driven effort.

Dowling separates ransomware operators into two groups: named and unnamed. Named groups are more trustworthy because they have a reputation to uphold, while unnamed groups are more likely to re-extort victims and deviate from the standards of ransomware negotiation, such as not providing proof of their claims.

Still, he said, most payments result in positive outcomes for the victims. The lowest payment Dowling has facilitated came in around $6,000, and the largest was about $8 million, he said.

Some negotiations end abruptly without further incident. These cases typically involve charities or non-profits, according to Minder.

One case he worked on involved a charity that provided free screenings for breast cancer. In that incident, he simply asked the attackers: “Why are you doing this? These people don’t have any extra money.”

The attackers walked away after the organization agreed to pay a $5,000 ransom to cover what the ransomware group claimed amounted to costs it incurred to conduct the attack — a significant discount from their initial demand of $2 million.

When cases involving data extortion come to a close, negotiators will ask for proof the data was deleted, which is impossible to confirm. Some attackers, who are especially proud of their work will provide detailed reports about how they gained access — information that helps the victim and incident responders understand how and what occurred.

Experts said the number of people involved in ransomware negotiations can be quite large when lawyers, insurance providers and law enforcement is involved. The duration of these back-and-forth compromises can last for a couple hours or up to three months.

Tactics define process for negotiation

Negotiators also employ generally similar strategies to achieve their client’s objectives at the lowest possible payment.

Threat intelligence on ransomware groups can guide negotiators toward a more gentle or aggressive approach, but in all cases “the threat actor, at the outset, has all the leverage,” Dowling said.

“The leverage that you have is the threat actor wants to get paid. The only way they’re going to get paid is if you come to an agreement,” he added.

Every ransomware negotiator CyberScoop spoke with remarked on the importance of delay. “Time is always our friend,” Cookson said. “Every day that passes after the initial incident is an opportunity for us to get more visibility so that they can make those decisions with a lot more confidence and make those decisions based on actual data, not based on fear and emotion.”

Initial outreach from negotiators working on behalf of a victim should be short and simple, allowing attackers to do most of the talking up front, Minder said. Negotiators should also avoid discussion of any financial numbers or positional bargaining as long as possible, he said.

Cursing or adopting combative language is a hard no-no for Minder as well. “There are ways to convey disappointment in the messages that aren’t fighting words,” he said. “They’re humans. They have egos, so you have to keep that in mind.”

Delay tactics are designed to get the attackers to question their own demand before the negotiator ever puts a number in writing, Minder said.

Moreover, it’s not just about the money — ransomware operators are seeking validation, and a sense that they’re in control and winning, he said.

The worst outcomes involve victims that rush to make a payment, assuming that will make all the pain go away, Cookson said.

Financial incentives present ethical challenges

Ransomware is a thriving criminal enterprise, amounting to a combined $2.1 billion in payments during the three-year period ending in December 2024 and about 3,000 total attacks in 2023 and 2024, according to the Treasury Department’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network.

Businesses, of course, see opportunity in all of that activity and boutique firms have assembled teams to support victim organizations by engaging in ransomware negotiations on their behalf in the wake of attacks.

This ancillary industry fosters additional ethical challenges, especially when there’s a built-in financial incentive for ransomware negotiations to occur and, in some cases, result in payments.

A general lack of transparency in billing puts the practices of some of these firms under heavier scrutiny. Some firms charge a flat fee or hourly rate, while others use a contingency model based on the percentage of the ransom reduction they’re able to achieve, DiMaggio said.

“It’s not the norm across the industry, but it happens, and it introduces a clear conflict of interest,” he added. “When a negotiator’s income depends on the ransom outcome, it blurs the line between representing the victim and profiting from the crime.”

While some ransomware negotiation providers do, indeed, charge a small percentage off the ransom payment, victim organizations should avoid hiring any firm that employs that model, Elovitz said.

“If you’re making a percentage of the payment, then at least there’s some financial incentive to not negotiate it down as far as you might otherwise,” he added.

DiMaggio would like to see more clarity around how service providers set prices for ransomware negotiation. Absent that, he said, “the industry will keep living in a moral gray zone, one where good intentions can unintentionally sustain the very ecosystem we’re trying to dismantle.”

Rules of engagement don’t apply

Ransomware negotiation remains an ill-defined, largely unrestricted practice, absent any collective industrywide agreement on rules of engagement.

Any effort to define rules upon which the industry can coalesce could potentially pit competitors against one another, leaving room for those more willing to bend the norms an opportunity to win business by providing less scrupulous services.

Negotiators are effectively unfettered once they ensure they’re not breaking any laws by engaging with or sending money to sanctioned criminals.

Still, there’s an unmet need for checks and balances, oversight, transparency and a standardized set of rules for negotiators to follow without crossing any professional or personal lines.

Part of the challenge with external oversight lies in the act of negotiation, an art that requires intermediaries to build limited trust with attackers spanning conversations that may not play well in the public sphere, Elovitz said.

“Putting that under a microscope could inhibit the good guys more than the bad,” he said. Payments themselves, however, could benefit from more scrutiny, Elovitz added.

Clarity in purpose should prevail above all of these factors.

Protecting victims without empowering criminals is the first principle of ransomware negotiation, but that balance can’t be managed in the dark, DiMaggio said.

“I’ve seen firsthand how the lack of oversight allows abuse from both sides of the table,” he said.

To prevent manipulation, DiMaggio called for a standardized framework, vetted negotiators, recorded and auditable communications and anonymized after-action reviews.

“Without accountability, the victims end up paying twice,” he said. “Once to the criminals, and again to the people who claim to save them.”

The scars from years spent as a ransomware negotiator brought Minder back to where his intuition was before he ever got involved. “I don’t believe this should be a business. I say that having been paid to do this,” he said.

“It’s almost like a parasitic industry,” Minder said. “You’re profiting from victims.”