The Pentagon may require vendors certify their software is free of known flaws. Experts are split.

Should the Pentagon require that vendors only sell the military software that’s free of known vulnerabilities or defects that could cause security problems? On the surface, it seems like a reasonable request.

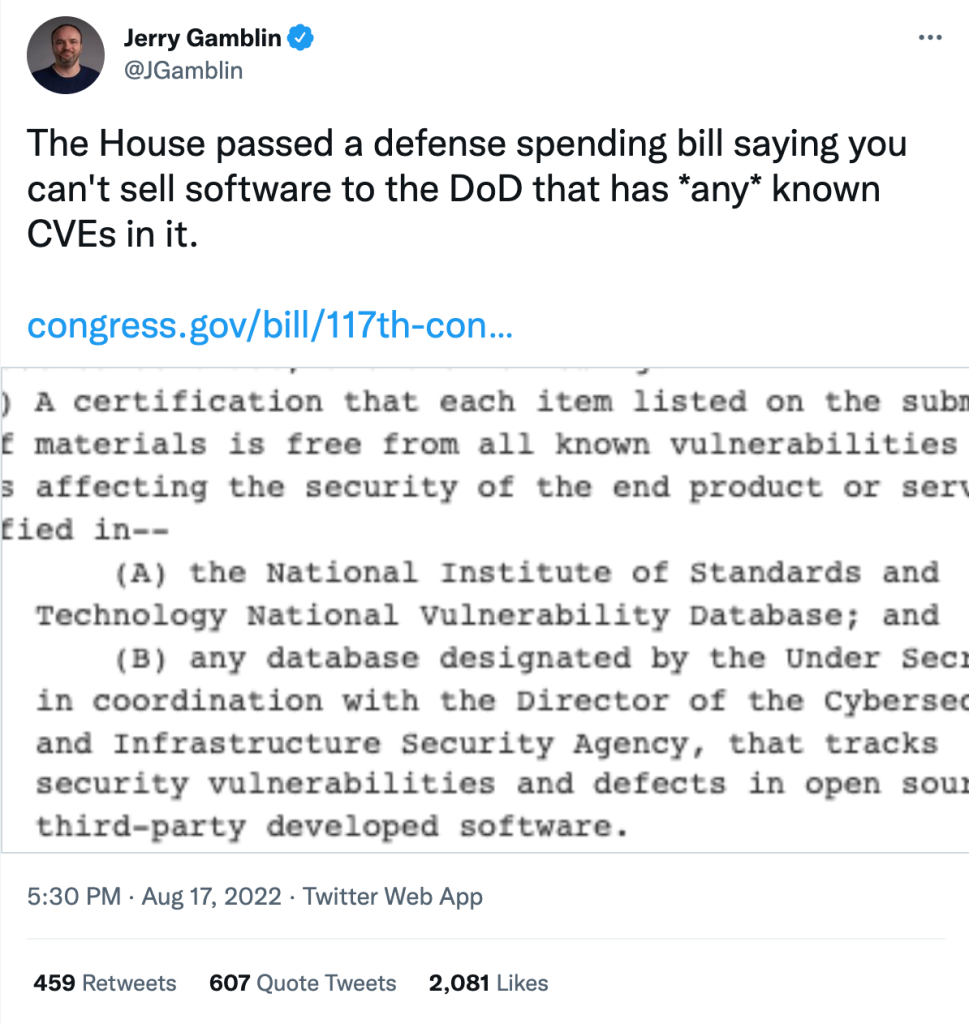

But when security researcher Jerry Gamblin tweeted a screen shot of the House of Representative’s software vulnerability provision from within the massive 2023 National Defense Authorization Bill — passed July 14 — it divided the cybersecurity community. The debate boils down to two key arguments: the requirement is unnecessary and impossible to achieve or a game-changing move that will begin holding software vendors accountable for selling faulty technology.

The Biden Administration is on the side of holding software vendors responsible for making sure their goods don’t contain known common vulnerabilities and exposures, or CVEs. The software industry should emulate the automotive industry, where “manufacturers retain ownership and responsibility” through the life of the vehicle, said Anne Neuberger, Deputy National Security Advisor for Cyber and Emerging Technology.

“The model in tech for too long has been that it’s the users’ responsibility to patch devices and systems and to recover from an incident when a vulnerability is exploited — and that model needs to change,” Neuberger told CyberScoop in an interview on Friday. “That certainly includes patching critical CVEs before a product is sold and maintaining visibility of new CVEs and responsibility for them.”

But cybersecurity executive Dan Lorenc argues there’s no such thing as vulnerability-free software.

“At first glance to someone outside the industry, it sounds perfectly fair to ban selling software with known vulnerabilities,” wrote Lorenc, a former Google software engineer and CEO of Chainguard, wrote in a blog post. “Why would you sell something vulnerable? And why would someone buy it? Especially an organization responsible for national security. But to anyone who has spent time looking at CVE scan results, this idea is just misguided at best and an impending s***show at worst.”

But it’s time to begin shifting more responsibility to software providers, argues Michael Daniel, a former senior cybersecurity adviser to President Obama and now the president of the nonprofit Cyber Threat Alliance.

Daniel pointed out there’s some wiggle room in the provision because it allows the contractor to identify the vulnerabilities or defects and a plan for fixing them. Another provision directs the Secretary of Defense to provide guidance for how and when to enforce these rules.

“This change would be pretty significant because software developers have long borne no liability for vulnerabilities in their products,” he said, adding that it would “mark a shift in the market.”

“The underlying principle that you should not be shipping software where you haven’t mitigated known vulnerabilities seems like a good one.”

michael daniel, cyberthreat alliance

Daniel doesn’t agree with Lorenc’s view that since there’s no such thing as vulnerability-free software, it is wrong to require companies to bear the responsibility for eliminating all known vulnerabilities before selling to DOD.

“The NIST [National Institute of Standards and Technology] database is well accepted as a source of vulnerabilities,” Daniel said. “It is true that not all vulnerabilities are created equal: Some are more dangerous than others and some are more likely to be exploited than others so there are definitely nuances in how much a defender cares about any given vulnerability.”

Daniel said he expects the guidance issued by the secretary would address that dynamic. “The underlying principle that you should not be shipping software where you haven’t mitigated known vulnerabilities seems like a good one,” Daniel said.

But Lorenc’s side includes plenty of vocal opponents of the proposed legislation, including prominent cybersecurity policy expert Harley Geiger who tweeted: “Policymakers: Please stop considering requirements to eliminate ALL software vulnerabilities, or bans on sale of software with ANY vulnerabilities. Please understand that not all vulnerabilities are significant, or can/should be mitigated.”

Lorenc also said that NIST’s National Vulnerability Database (NVD), a government repository of standards based on vulnerability management data, is unworkable at scale. “Vulnerability data is bad; like really, really bad,” Lorenc wrote in his blog. “As an industry we have not figured out how to accurately score severity, measure impact and track known vulnerabilities in a way that is scalable.”

Lorenc said many organizations don’t know all of the software they’re using. He pointed out that the technology research firm Gartner found that up to 35 percent of IT spend was on software that owners didn’t know about.

In an interview, Lorenc said that the fundamental problem is that there’s no universal definition of a vulnerability. He said many of the vulnerabilities included in the NIST database are either partially incorrect or don’t always apply.

“We don’t have a shared vocabulary for explaining all of that and so a lot of the stuff in there really comes off as just noise and there’s no great way to filter it out or correct it,” Lorenc said. “So the NVD tries to be as open as possible, but it leads to a lot of the corrections happening in an unstructured way that makes it hard for tools and systems to track.”