Kaspersky Lab looks to combat ‘stalkerware’ with new Android feature

The proliferation of commercial spyware is one of the more pernicious trends in cybersecurity that affects technology users worldwide.

Once installed on a phone, this kind of malicious software can access a victim’s text messages, geolocation, and social media information, along with other data. So-called stalkerware is cheap and readily available online. It allows, for example, jilted lovers to snoop on former partners, and has been linked with domestic abuse.

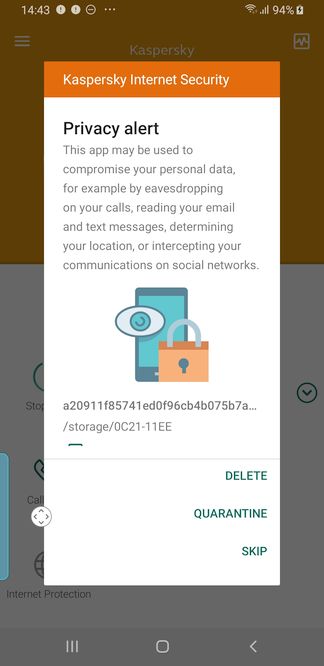

To put a dent in this scourge, cybersecurity company Kaspersky Lab has added a feature to its Android antivirus app that alerts users if their data is being tracked by known spyware. The warning flags a file on the user’s phone and offers to delete or “quarantine” it.

And there are a lot of invasive apps to flag: Kaspersky Lab said its products detected stalkerware programs on more than 58,000 different mobile devices in 2018, including 26,619 “unique samples” of programs.

“We believe users have a right to know if such a program is installed on their device,” said Alexey Firsh, a Kaspersky Lab security researcher.

A screenshot of the new feature (Kaspersky Lab)

Kaspersky Lab also advised users to only install mobile apps from official stores and to change their mobile security settings if they are leaving a relationship.

The company’s release of its new Android feature comes as the Electronic Frontier Foundation’s Eva Galperin is pushing the antivirus industry to do more to combat this kind of surveillance, as Wired first reported.

“I’m very pleased to see Kaspersky taking spouseware and stalkerware seriously, given the antivirus industry’s history of mostly ignoring this threat,” Galperin told CyberScoop. “I look forward to seeing other antivirus vendors follow suit.”

Many stalkerware programs are aggressively advertised online, meaning it takes little guile or technical acumen to find a program and then, with access to a target’s phone, install it. In addition, apps that are marketed to help parents monitor their kids can be turned on spouses, co-workers, or other victims.

“Forget Darkweb forums or underground markets, developers of these applications have built their own economic environment,” wrote Kaspersky’s Firsh. “They provide different offers for different needs, with tariffs ranging from half a dollar per day to $68/month.”

In one case highlighted by the New York Times last year, a husband reportedly used an app to monitor his wife’s communication in the days before he murdered her. In another, counselors at a safe house for battered women in Minnesota had to call the police after a man used an app to track his wife to the shelter, according to NPR.

Vigilante hackers have been known to breach spyware applications, exposing their security flaws to the world. Such was the case last year when a hacker wiped some servers of Florida-based Retina-X Studios, Motherboard reported.

“Overall, we found that five out of the 10 most popular stalkerware program families had poor security or had leaked a tremendous amount of personal data due to breaches,” Firsh wrote in research published Wednesday.

Firsh said some stalkerware programs also share server infrastructure, meaning if a hacker exploits a vulnerability in the command-and-control server of one product, other products will have been compromised, too.