Power struggle: Government-funded researchers investigate vulnerabilities in EV charging stations

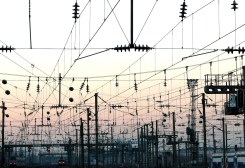

Charging stations for electric cars have sprung up across the country in recent years as hybrid vehicles continue to gain popularity. As those stations carry more wattage, their potential effect on local power flows has grown.

The trend caught the eye of researchers at a top government cybersecurity lab, who have embarked on a multiyear project to learn how hacking a charging station might disrupt the quality and flow of power through a local grid.

Kenneth Rohde, a cybersecurity researcher at the Idaho National Laboratory, explained the project to a room of engineers and hard-hat hackers at the S4 Conference last month in Miami.

In a video, Rohde approached a charging station and ran an attack on the human machine interface (HMI), which affects the charging process by communicating with a control system.

“Now you’ll see this power meter is jumping all over the place,” Rohde said. He executed a spoofing command to trick the charging station into thinking the vehicle was 90-percent charged when it was really at a third of its power. He ended the demonstration by issuing an emergency command that abruptly halted the charging.

“If we can get a foothold on the HMI, then the way this system is currently architected is that HMI has full control of everything in the [power] cabinet” that is central to the charging station, Rohde told CyberScoop.

Like a lot of industrial equipment, charging stations were built with safety, rather than security, top of mind. The vendors involved in the project don’t fall into that category, Rohde said, describing them as companies that understand cybersecurity risk. “The problem is there is already equipment out there” that wasn’t designed with rigorous cybersecurity protections, he added.

In January, French energy management giant Schneider Electric issued patches for three security flaws in its charging stations, the most serious of which involved hardcoded credentials like default passwords or embedded security keys.

As foreign hackers have shown a steady interest in mapping the industrial control systems that underpin U.S. electric infrastructure, engineers and cybersecurity specialists have gone to greater lengths to fortify that infrastructure. Rohde’s experiment, though not stemming from a particular threat, is one facet of that preparedness. And grid operators are increasingly considering how charging stations affect local power ecosystems.

Dialing up the wattage

Electricity operators work to balance the distribution of power to businesses and homes across the country. When measured, a steady and reliable power flow generally has a smooth, sine wave form. Variations in the flow can lead to an increase in total harmonic distortion, which means the quality and reliability of the power flow has decreased.

By commandeering the charging station, Rohde’s hacking demo ramped up the total harmonic distortion of the power flowing through the station. He intends to further investigate how a local grid would react to that disruption in power quality.

“We’re not sure what the grid is going to say as far as what is acceptable or not acceptable,” he said. “That’s why the utility partners are going to be helping us answer that question.”

The INL-run project is an experiment in fairly unchartered territory. Rohde’s team is examining the emerging areas of wireless and “extreme-fast” electric-car charging, where the threat vectors aren’t known. The attacks he demonstrated haven’t been seen in the wild, but that’s the whole point of the research: to anticipate how adversaries might evolve to exploit emerging areas of connectivity.

INL is working with two big utilities (Rohde wouldn’t name them), charging-station vendors ABB and Tritium, the charging network operator Electrify America, and two other Department of Energy labs – Oak Ridge National and The National Renewable Energy Lab.

“We know that there are going to be engineering improvements on the [charging] equipment itself,” he said. “That’s why we have the industry partners involved so as we find potential flaws in their systems, they can hopefully engineer them out.”

Power-sector professionals have had varied reactions to Rohde’s research, he said. Some say that a disruption to a charging station is just another power load they have to manage. Engineers that are drilled into the details, however, have raised their eyebrows.

“You mean you’re going to have a 2 MW load that disappears in 1/20,000 of a second? That’s not really acceptable,” he said, paraphrasing their reaction. That is a reference to the emergency-stop command Rohde issued in the demonstration, which powers off the charging station, quickly taking electricity off that part of the grid. There’s no impact to the local grid if a 50-KW station does that, Rohde said, but he is changing the parameters to explore what happens if hundreds of stations shut down simultaneously, or if higher-wattage stations are involved.

With over two years left on the project, Rohde aims to raise greater awareness of the potential vulnerabilities in charging stations. The next step is to test a 350KW fast-charging station, which draws roughly enough electricity to power the air conditioning units in two large apartment buildings.

Back at INL headquarters in Idaho Falls, Rohde is waiting for the equipment to arrive any day now. “We are anxiously waiting to start working on this new system,” he said.