Dark Pink, a newly discovered hacking campaign, threatens Southeast Asian military, government organizations

A recently discovered hacking campaign is targeting a range of organizations across the Asia-Pacific region, and one in Europe, as part of a sophisticated effort to steal corporate data and other high-value secrets, researchers with the cybersecurity firm Group-IB said Thursday.

The so-called “Dark Pink” campaign surged in the second half of 2022 and has, to date, been responsible for seven successful attacks, Group-IB researchers Andrey Polovinkin and Albert Priego said in a detailed analysis. Its primary goals seem to be corporate espionage, document theft, sound capture from the microphones of infected devices and data exfiltration from messengers, according to the researchers’ analysis.

The researchers did not attribute the campaign to any group, “making it highly likely that Dark Pink is an entirely new [advanced persistent threat] group,” the researchers said. But another security firm, the Chinese company Anheng Hunting Labs, linked the campaign to a “suspected southeast Asia” in an analysis published Jan. 5, according to a Google translation of its analysis.

Of course, the Asia-Pacific region is home to a variety of ongoing state-aligned cyber activity, representing a wide range of competing interests and agendas. From China to North and South Korea to Taiwan and Vietnam, there is no shortage of ongoing cyber operations run or sponsored by governments targeting each other or domestic entities.

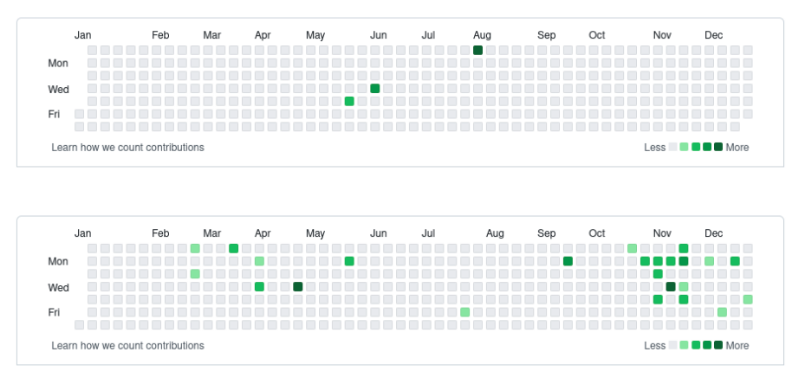

The known Dark Pink attacks that Group-IB analyzed started with an attack on an unnamed religious organization in June 2022 in Vietnam. But the group was likely active at least dating back to May 2021, which is when a Github account the attackers used became active. Other known victims include a Vietnamese nonprofit, an Indonesian governmental organization, two military bodies in the Philippines and Malaysia and government agencies in Cambodia, Indonesia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, the researchers said.

Potential victims have been notified, the researchers noted, and there are likely more that have yet to be uncovered.

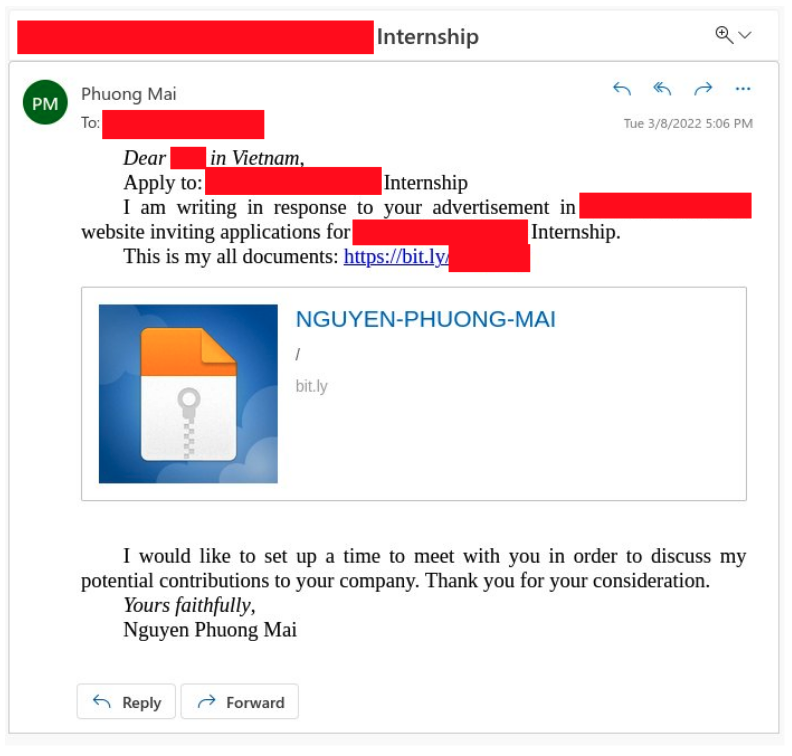

The attacks began with spear-phishing emails likely designed specifically for each target. In at least one case, attackers posed as an applicant for a public relations and communications intern role, suggesting they scan job boards to target victims. North Korean hackers have been known to employ similar methods, the U.S. government warned in May, as a means to both generate revenue for the North Korean government and perhaps gain access to corporate networks.

A shortened link within the email includes both malicious and innocuous documents that deliver the malware used to further the operation.

The researchers said the attackers can exfiltrate data in three ways: Sending it via Telegram, transferring files to Dropbox and via email.

The email method was “of particular surprise,” the researchers noted. The email addresses used included blackpink.301@outlook[.]com and blackred.113@outlook[.]com, among others. The body of the email simply read “hello badboy,” while the subject line was the specific device’s name, according to data collected by the researchers.

Ultimately the findings show that innovation in attacker techniques can have profound consequences.

“The threat actors behind Dark Pink were able, with the assistance of their custom toolkit, to breach the defenses of governmental and military bodies in a range of countries in the APAC and European regions,” the researchers said. “Dark Pink’s campaign once again underlines the massive dangers that spear-phishing campaigns pose for organizations, as even highly advanced threat actors use this vector to gain access to networks, and we recommend that organizations continue to educate their personnel on how to detect these sorts of emails.”