While U.S. ponders response to Russia, agencies’ hands are tied in cyberspace, intelligence chief says

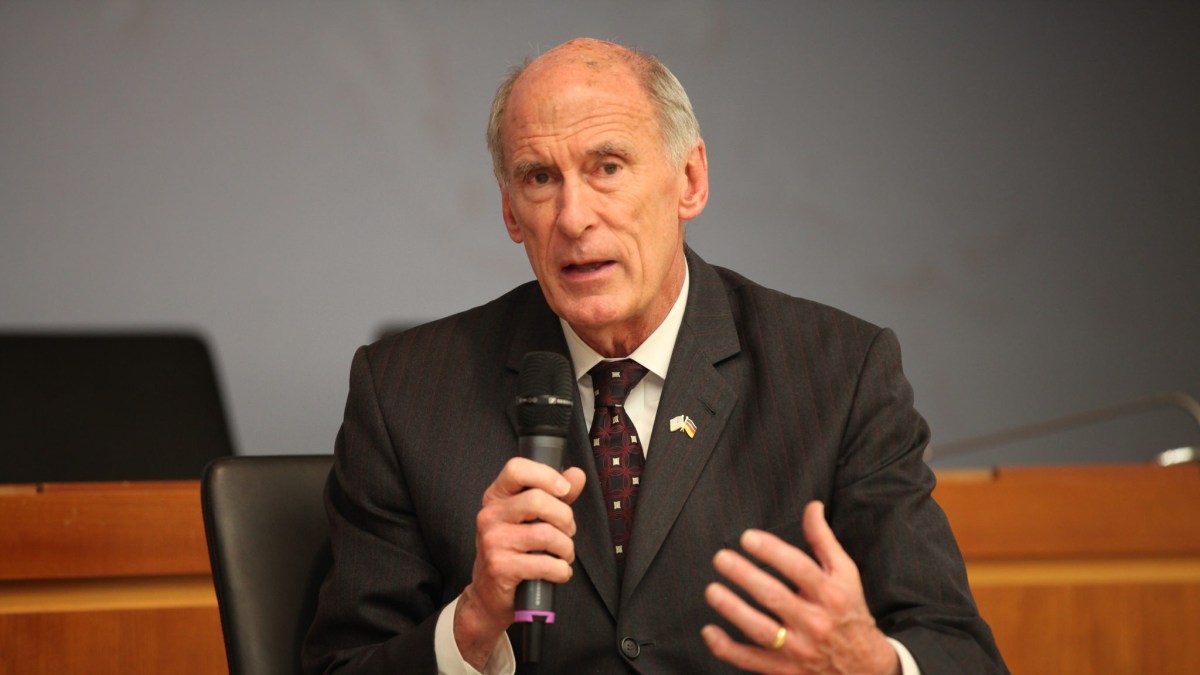

After senators repeatedly criticized him for the weak U.S. response to Russian cyberattacks and propaganda, the head of the intelligence community complained Tuesday that a lack of policy had stifled his agencies from taking action.

The White House is currently involved in various policy discussions with intelligence agencies, the Pentagon and the Homeland Security Department about how to best counter Russian operations, said Director of National Intelligence Dan Coats. But there’s still no timetable for when any of these policies will be either introduced or codified into law.

In the meantime, “Russia is likely to continue to pursue even more aggressive cyberattacks with the intent of degrading our democratic values and weakening our alliances,” Coats said Tuesday at a hearing by the Senate Armed Services Committee.

The National Security Council, White House Homeland Security Adviser Thomas Bossert and White House Cybersecurity Coordinator Rob Joyce are discussing the appropriate policy and legal framework necessary for U.S. intelligence and military agencies to respond to Russian aggression in the digital domain, said Coats, who described the effort as a “whole of government approach.”

The problem for U.S. agencies — as most national security experts would say — is that the United States and Russia aren’t at war. The Intelligence Director provided no timeline for when he expected any policy decision from the White House, but hinted that the intelligence community was currently hamstrung in its ability to counter some emerging cyberthreats without the creation of new and additional laws.

Senators repeatedly pushed Coats to describe which federal entity is currently or should be taking the lead in the future to mitigate Russian disinformation campaigns and other digital meddling similar to what Russian troll farms did during the 2016 election.

“This is more of whole of government approach, DHS plays the primary role [in election security] but other agencies are also involved. This is an ongoing process of putting a policy in place,” Coats said. “That decision [about how to counter foreign propaganda] needs to be made by the president and White House. We do have a Cyber Command through the military.”

Coats’ reference to Cyber Command’s role is a bit confusing because there’s little public evidence to suggest that Cyber Command holds any inherent legal authority to go after “fake news,” malicious social media activity or foreign computer systems launching cyberattacks from beyond U.S. soil.

In response to a series of questions offered by Republican Sen. Mike Rounds, who heads up the committee’s cybersecurity subcommittee, Coats admitted that no clear or concise policy concerning cyberwarfare exists today.

“I don’t think the progress has been made quick enough to put us in a position with a firm policy,” Coats said. “We still haven’t from a policy standpoint, from the executive branch or congressional branch, exactly defined what that is or how we’re going to support those defenses … the question of response is something I think that really needs to be discussed because there are pros and cons about how we should do that. I have personally been an advocate for playing offense.”

He continued, “We don’t have an offensive [cyber] plan in place that we’ve agreed on should be the policy of the United States.”

The grilling followed two other, separate congressional hearings last week that saw the current NSA director and his successor, Adm. Mike Rogers and Lt. Gen. Paul Nakasone, testify in front of the same Senate committee. During that appearance, Rogers said he had never been specifically directed by the president to stop Russian cyberthreats where they originated — meaning he had not been authorized to strike systems based overseas, which would require approval from the Oval Office.

Coats backed Rogers’ prior statement but briefly mentioned that the NSA is far from the only intelligence agency capable of responding to Russian cyberattacks. Current law stipulates that the CIA is the main body responsible for covert operations unless the president directs otherwise. Experts say the CIA’s covert action authority relates both to the physical and cyber domains.

“It is clearly an issue for the National Security Agency and NSC at the White House,” Coats described. “There has not been yet a formulation of a lead agency that would work with the Congress on legislative action or putting policy in place. There are some complicated issues here related to retaliatory action.”

The NSC did not respond to a request for comment.