Microsoft banks on new silicon chips built by Intel, others to fend off firmware attacks

Microsoft is pushing an initiative meant to protect its computers’ most sensitive data amid recent revelations that nation-state hackers are beginning to exploit the fragmented nature of the company’s supply chain.

The company on Monday started pushing Secured-core PCs, its term for machines that will come with Windows 10, Microsoft’s latest PC operating system; Windows Hello, which allows users to log in without a password; and, most importantly, silicon microchips built by Intel Corp., Qualcomm and AMD that are meant to more closely guard sensitive data.

By ensuring that PCs are loading legitimate Windows operating systems when a devices activate, the plan goes, Microsoft will ensure that users aren’t actually loading a malicious OS inserted by an outsider.

The effort goes public more than a year after security researchers at ESET caught APT28 — a group of suspected Russian hackers also known as Fancy Bear — testing out malware that launched malicious code on a computer when it was booting up. In that case, attackers aimed malware at firmware, the permanent code within a device’s memory, to infect victims in a way that could have given them access to stored credentials, and a device’s memory. The new silicon chips will secure machines in a way that protects them from this kind of threat, said David Weston, Microsoft’s partner director of enterprise and OS security.

“Today, the firmware is the first thing that loads,” he said. “That means that before Microsoft code even loads, the firmware is deciding whether it wants to run Microsoft code or some malware. We’re deciding that in a Secured-core PC, the CPU is going to validate that the code is signed by Microsoft before it’s allowed to load.”

The timing of Microsoft’s initiative coincides roughly with a U.S. National Security Agency plan to publicly release a platform that aims to isolate machines’ firmware in a container to keep it away from potential attackers. The final product, dubbed SMI Transfer Monitor with protected execution, will run as part of Coreboot, an existing software project, NSA officials told CyberScoop in August.

Compounding the issue is that endpoint security products typically don’t have visibility into the firmware layer, because they run in the operating system, Weston added.

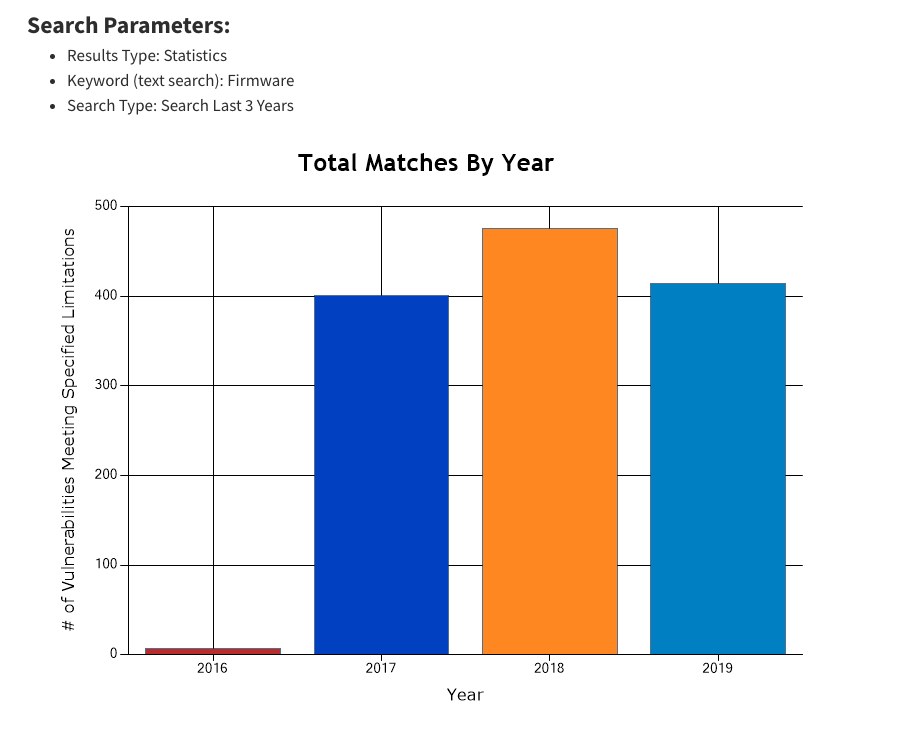

A cursory search of the National Vulnerability Database, from the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology, returned a graph showing a steep uptick in the number of firmware vulnerability searches there in recent years.

(NIST)

Only one malware strain affecting firmware vulnerabilities turned up in VirusTotal, a malware repository. In that case, none of the 64 antivirus providers assessed by VirusTotal were capable of detecting the issue.

Microsoft’s effort marks a step forward, according to independent firmware experts who reviewed the plan at CyberScoop’s request. The current landscape relies on a static root of trust, meaning that a complete computer reboot from scratch is the only way to restore a secure, trusted state. Secured-core PCs, with those silicon chips will utilize a more dynamic root of trust, which provides a stronger kind of authentication than existing Basic Input/Output System (BIOS) firmware.

“Fundamentally, BIOS vendors and OEMs are doing a very poor job and shouldn’t be trusted,” said Joe FitzPatrick, a hardware security trainer and researcher. “This is a way of bridging trust from the processor to the OS, regardless of what the BIOS does.”

‘How the hell do we do something similar?’

Secured-core PCs have been in the works for years, after Microsoft’s internal security team sought to replicate the level of protection in Xbox gaming systems in its enterprise machines. In the same way that Apple enforces tight safeguards on its ecosystem, Weston says Microsoft has similar control over the Xbox — but not over PCs.

“The question was: How the hell do we do something similar with our PC system?” Weston said. “If you design a system that’s very closed over hardware and software, frankly, security is just a lot easier … and, unlike the iPhone we want to give users a lot of choice.”

While Apple relies only on Intel to build its processors — and still is switching to manufacture its own by next year, according to Bloomberg — Microsoft works with Intel, AMD and Qualcomm. And firmware typically is distributed by original equipment manufacturers, so Microsoft typically doesn’t have the visibility to include security updates in its monthly Patch Tuesday releases.

“We went to all our silicon vendors and said we would like to eliminate firmware from the root of trust,” he said.

The new chips leverage System Guard Secure Launch, a startup process embedded in Windows Defender, to send the operating system’s boot loader, which initializes the OS, and processor functions down a predictable and trustworthy path, Microsoft said. The protocol also involves Microsoft’s virtualization-based security, which isolates the memory in an operating system, to keep malware out of a computer’s kernel and other sensitive functions.

“Virtualization-based security has been around since 2015, and that’s great,” Weston said. “But our viewpoint is that we want to get more of this technology across our user base. Out of the box, these have virtualization turned on and they’re segmenting stuff.”

Secured-core PCs will be introduced over the next year, Microsoft says, first with enterprise computers at corporate clients and then made available to individual consumers.