The politics and power of Latin American hacktivists Guacamaya

At a press conference in Mexico City last October, about a month after a massive leak of secret government and military documents created a domestic political firestorm, Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador attempted to downplay the ensuing controversy. He told reporters his opponents failed to use the information against him and mocked the hacktivists behind the breach, a group calling itself “Guacamaya,” the Mayan name for a macaw.

“This macaw,” he said, with a wave of his hand and a wink, “has become a buzzard.”

Despite the president’s attempt to dismiss the hacktivists, the little-known group came from nowhere to shake power centers across Mexico. The data dump quickly blew up on social media and dominated headlines for weeks. Some of the most politically damaging information related to how López Obrador apparently misled the public about his health, the Mexican military’s control over the civilian government and how the military hid claims of sexual abuse against women. The cache of documents also contained details about potential public collusion with cartels and the government’s use of spyware against journalists.

Guacamaya has put Latin American governments and global corporations with a Latin American presence on notice that it wants to expose state secrets, business dealings and the intimate details of whatever else the group deems corrupt. “Anything that represents oppressive states, multinational corporations and, in short, anything that supports this system of death,” is fair game, the group told CyberScoop in an email.

Over the course of an extended email exchange with the group’s official email address, CyberScoop sought to understand more about Guacamaya’s aims, its goals, how they carry out operations and who they are. The group preferred to respond to questions in Spanish, which CyberScoop then had translated.

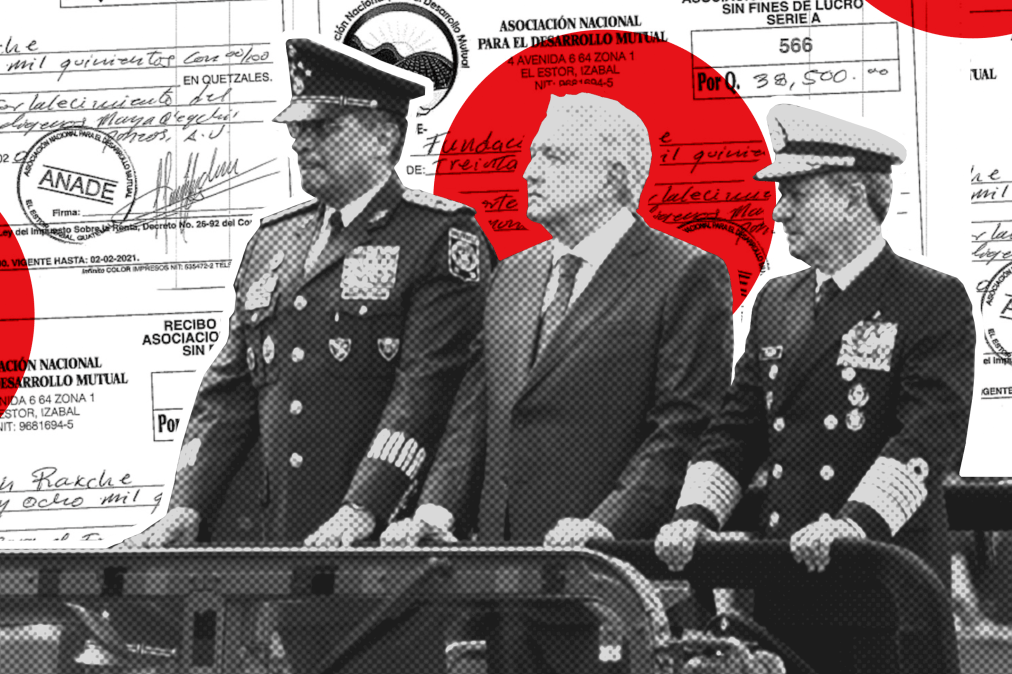

Guacamaya has released between 20 and 25 terabytes of stolen data since March 2022, including files it provided the nonprofit news site Forbidden Stories a year prior for an exposé about corruption involving Guatemalan officials and a Swiss mining conglomerate. Their hacking operations have targeted what the group says is the exploitation of indigenous lands throughout Mexico and Central and South America. So far, the leaks have led to the resignation of one of Chile’s top military officials.

“Guacamaya is definitely one of the most responsible and impactful hacktivist groups we’ve seen in recent years,” said Emma Best, a journalist and transparency advocate who co-founded Distributed Denial of Secrets, or DDoSecrets, a nonprofit “transparency collective” that hosts hacked and leaked material and distributes it in the public interest to journalists and researchers. Fuerzas Represivas — the campaign published Sept. 19 that included more than 13 terabytes of data — ”was the largest leak in history, and instead of dumping the files on the open internet they came to us and Enlace Hacktivista and asked us to make sure journalists and researchers were able to work with the data.”

The impact in Latin and South America, Best said, “has been large but understated, and its full effect is going to continue to play out for months and years to come.”

THE HACKERS

It’s not clear who the hackers are, nor where they live. They would not answer specific questions about their backgrounds or technical abilities. “We are regular people, we are people from any city, town, region who became aware of this tool,” they said. “Anyone can do what we have done.” They say their efforts are driven by the “invasions and oppressions” Latin Americans have faced over the years. And they are attempting to fight back in the best way they know how — through hacking.

The group makes its leaks available upon request either to Enlace Hacktivista — a website dedicated to hosting hacked materials and messages from hackers — or DDoSecrets. Both sites say they evaluate the requester before providing access. Best said requesters are evaluated on their past work, whether they contribute to journalism or public research, and that those with vague goals and other concerns are denied. Enlace Hacktivista did not respond to a request for comment.

The members of Guacamaya with whom CyberScoop communicated said they’re aware of the widespread speculation about their identities and on whose behalf they operate. The group’s critics have questioned whether they’ll attack only left-wing governments and have accused them of working with the CIA, they said. “It seems to us like a desire to distract and to lose our message in these discussions,” they said. “We notice an attitude of disbelief when we say that we are ordinary people. They are surprised and do not believe in the capacity of our communities, of us, common people. They only believe in the capacity of great powers. That is how they have dominated us, using denigration and humiliation.”

With each hack, Guacamaya publishes a lengthy treatise, all of which have hit a similar theme: The corporate and government power structures throughout Abya Yala — an indigenous term for the American continent in its entirety — enable an exploitative and violent system that ensures the subjugation, abuse and misery of local populations in service of American and European capitalists.

“The police entities of Abya Yala, like the army, are armed entities that guarantee oppression, injustice and terror against the peoples, guaranteeing the dispossession of the land of peasants, indigenous and Afro-descendant people,” the group wrote in the message posted with Fuerzas Represivas, or Repressive Forces, the release that contained six terabytes of Mexican military documents. “They guarantee extractivism. They guarantee neoliberal and capitalist systems.”

The group also posts messages about their operations and their justifications for carrying them out on Enlace Hacktivista and DDoSecrets. A review of the communiques, as well as the correspondence with CyberScoop, suggests multiple authors either collaborating or penning the individual messages. The group confirmed the diversity of its membership in a message: “Cierto, no somos ni una persona ni un pueblo sino muchos pueblos,” they said. We are neither one person nor one people but many peoples.

Juan Andrés Guerrero-Saade, senior director of SentinelLabs and a former senior cybersecurity and national security adviser to the government of Ecuador, agreed that most analysts or officials expect operations such as these, with major results, to have connections to nation-states or criminal syndicates.

“For those of us who have grown accustomed to nation-state plays, or criminal plays that ultimately have some semblance of a goal and expect some kind of [return on investment], it’s that much harder to understand someone who says, ‘Well, you know, we’re just doing this because f— you, that’s why,” he said.

Furthermore, many threat researchers are generally unfamiliar with Latin America’s political and socio-technical context. The region is “particularly underserved on all things cyber, whether defense against prolific and long-running cybercrime or nation-state operations, both local and from abroad, Guerrero-Saade said. “Latin America is not being prioritized or well served,” he said, due to a variety of reasons such as finances and complex local context. “If you’re not there, if you don’t care, if you don’t know what’s going on, it’s very hard to do that properly.”

Gabriella Coleman, an anthropology professor at Harvard who’s studied and written extensively about hacker culture, said that although it’s notoriously difficult to know truly who’s behind these kinds of operations, “aesthetics and style actually may make a real difference.”

Guacamaya pairs its leaks with videos, vivid illustrations that evoke indigenous artwork and music, alongside the messages for every hack. The videos include catchy hip hop, with lyrics flicking at revolutionary and people-powered themes with a hint of hacking sprinkled throughout. “A lot of care went into the music,” the group told CyberScoop.

The “political and aesthetic sensibilities” of the group are front and center in their public pronouncements, Coleman said. “In that sense, I think that these really are authentic political activists coming from the ground up, as opposed from the top down.” For instance, she said, their style demonstrates a deep understanding of Latin American culture and political ideology. In many ways, their approach resembles the work of Phineas Fisher, a leftist hacktivist perhaps best known for targeting digital surveillance companies.

For Tom Uren, formerly of the Australian Signals Directorate and a current editor with Seriously Risky Business cybersecurity news, assessing hacktivism claims comes down to “does what they hack and what they leak actually line up with what they say, and does that line up with their capabilities and the vulnerabilities they’ve claimed to exploit.

“On all those metrics, Guacamaya pretty much seems authentic,” Uren said. “Usually, the state-backed groups, they don’t bother to make such a good effort,” he added. “There’s no reason a state backed group couldn’t make an effort, it’s just that they typically don’t bother.”

THE HACKS AND IMPACT

While the group’s hack-and-leak operations have gained global attention, real world consequences are harder to assess. The most direct and high-profile impact occurred in Chile, where Gen. Guillermo Paiva Hernández, head of the country’s Joint Chiefs of Staff, resigned in September over the embarrassment of the leak.

Officials in Peru attempted to quash coverage of the leaks there. A Peruvian military official threatened to bring treason charges against Ernesto Cabral, a journalist with the independent Peruvian news outlet La Encerrona, when he initially reported on the material, the reporter told CyberScoop.

La Encerrona wrote extensively about Guacamaya’s Peruvian leaks, covering revelations the Peruvian military had been monitoring left-wing parties and specific left-wing figures as threats to the state. The files also revealed that the Peruvian military deemed civil organizations in the region a threat because they “infiltrate and advise the population against mining,” La Encerrona tweeted, according to a Google translation.

Cabral said journalists and NGOs in Peru are now more cautious with their communications after the military files revealed extensive monitoring of reporters. Overall, the reaction among the public and the politicians has been mixed, he said.

“The majority of the politicians here, the lawmakers and also the president, they agree that this kind of behavior from the military and police is OK, there isn’t anything wrong in doing it,” Cabral said. “That was also one of the main responses we had, at least on social media, from a lot of citizens.” Cabral noted that an earlier hack-and-leak operation targeting Peruvian law enforcement records in April 2022, allegedly carried out by a person affiliated with the Conti ransomware gang, had already begun to reveal government misdeeds, perhaps dulling the public reaction to the Guacamaya operation.

But there has been “major coverage from a lot of newsrooms” across the country, he said. “Because the army was targeting their politicians, their representatives, the NGOs working in the south of Peru supporting the community against what they call misbehaviors of the mining companies,” he said. “So it was relevant for them.”

A big part of the story, Cabral noted, was that the Guacamaya files revealed information that “threatened the lives” of Peruvian soldiers battling drug trafficking organizations. This was one of the reasons why Cabral and some other journalists were frustrated when the Peruvian military tried to downplay the information. “There is sensitive information,” he said. “Information that can be dangerous, not only for the NGOs or the civil society, but for the soldiers.”

Similar safety concerns surfaced in Australia. In October, the Sydney Morning Herald reported that the leaks related to Colombia “exposed the identities and methods of secret agents working to stop international drug cartels from operating in Australia.” Details from 35 Australian Federal Police operations, some ongoing, were leaked, and “many overseas police agencies were also affected,” the paper reported.

An AFP spokesperson told CyberScoop in a statement that the agency is “concerned about possible breaches of operational security as a consequence of this data compromise.” Additionally, the agency is “assessing the information that may have been obtained from Colombian law enforcement as part of this hacking activity,” and is working with “international partners” and Colombian law enforcement to “safeguard their computer systems.”

The group does appear to consider the potential harm. For instance, Guacamaya required anyone who wanted the Fuerzas Represivas dataset to directly request access to it. In a message posted alongside the Mexican military documents, the group said it wanted “everyone to have access to the leak,” but that was not possible “since there is information that in the hands of drug traffickers could put many people at risk.” Even still, the materials had been shared with several journalists, the group said, “whether we like [their] politics and [their] reporting or not.”

In Chile, reporters used the documents to expose Peru’s contingency plans for potential war with Chile. “Everything is there, from the trajectories that the units would follow, to the deception strategies that would be implemented to distract the Chilean forces,” Chile’s Center for Journalistic Investigation reported. In a separate story, the center reported on “highly sensitive” files related to Colombia’s military and political relationship to the U.S., Washington’s fears about Chinese influence in South America and apparent Russian military communications systems operating in Venezuela near the Colombian border.

The leaks also revealed detailed coordination between U.S. and Mexican armed forces in the fight against drug trafficking, El País reported in October. The files showed that although Mexican President López Obrador “may have said that Washington has not been involved in the recent offensives against organized crime, the two countries have been working closely together,” the paper reported.

In Mexico, it will take months or perhaps years for the information contained in leaks to be verified and reported by journalists or researchers, and this has contributed to stories from the leaks largely fizzling out, said Hiram Alejandro the co-founder and CEO of cybersecurity firm Seekurity in Mexico City. Many reporters aren’t technically equipped to access the large amounts of data and parse it for stories, or they don’t want to press too hard on sensitive information given that Mexico is one of the most dangerous places in the world for journalists. And the Mexican government’s downplaying of material included in the leaks has further diminished the story’s momentum.

According to Alejandro, a “well-known” Mexican reporter who told him that they wanted to dig deeper into the files, but they didn’t want to put themselves in danger. Exposing both sensitive information and the lack of basic cybersecurity could help Mexico’s adversaries attack the country, or steal information.

Alejandro and his journalist friends aren’t the only ones pointing out the difficulties many local reporters face attempting to cover the leaks, whether in Mexico, Peru, Chile, Colombia or elsewhere in Latin America.

Guacamaya also acknowledges the dangers. In its first interview, the group told Forbidden Stories’ Laurent Richard that one of the reasons it shared its first hack with the French-based consortium was because “being an international media made it less risky,” and that “sending it to the local press would put them at risk because they have already been imprisoned or threatened.” Exposing Mexican military documents could reveal details about operations against drug traffickers, Guacamaya said, and “put many people at risk.”

Guacamaya declined to say whether more leaks are coming — ”we are looking at some things, we can’t say more” — but also said they aren’t worried about governments they’ve exposed, or corporations they’ve embarrassed, to come back at them. “We are the people whose rights have already been violated and against whom these states, this oppressive system in all aspects, have exercised all kinds of abuses,” they told CyberScoop. “We do not know if they can do more to us. We doubt it.”

Translated by Patri González Ramírez