Fin7 weaponization of DDE is just their latest slick move, say researchers

When cybercrime gang FIN7 weaponized a new attack vector against Microsoft applications within a day of it being published last week, it was just the latest slick move from a threat group who’ve been consistently one step ahead of cyber defenders.

A timeline of different attack vectors used by the group compiled by Morphisec researchers shows that FIN7 typically adopts a new technique within “a couple of days” of an attack being discovered, once the number of security solutions that detect it gets into double figures.

The Morphisec researchers analyzed scoring of FIN7 attachment lures by VirusTotal — a service that scans files and tests them against 56 kinds of security software.

“A look at Virus Total scoring reveals that when a FIN7 campaign is first active, is goes mostly undetected by security solutions. The malicious documents do not score more than 1-3 detections. Within a couple of days, security solutions update their patterns and those documents score around 10/56 or higher,” according to their report.

But by that time, the authors write, FIN7 is already deploying new tools, by simply tweaking the code or other patterns that the security software is hunting for. This technique “diminishes the usefulness of reactive, pattern-based detection rules,” according to Morphisec.

Other researchers have analyzed FIN7’s tactics, noting that they follow a familiar pattern for skilled hackers: Initial compromise; establish foothold; escalate privileges; maintain presence; move laterally; and finally complete mission.

The constant shifting of attack modes is “At the heart of FIN7’s business model,” the Morphisec researchers conclude. “Every campaign includes enough new features to make them unknowable … And as security vendors scramble to catch up, FIN7 is already preparing its next attack.”

Indeed, that swift adoption of new techniques caused one researcher at InfoSecurity Europe to comment of FIN7, “In most environments, prevention is not possible,” and detection is the best defenders can hope for.

Earlier this year, when FIN7 encountered a Morphisec researcher during an incident response, the group first blocked the IP he was using and then abandoned their entire command and control infrastructure.

Such caution is worthy of a high-end financial cyber crime group thought to be behind many of the most audacious recent online bank thefts — including the one identified by Kaspersky dubbed “Take the money, b*tch!” after a line of instructions in the code.

The group were among the first to adopt super stealthy fileless malware — an attack method in which hackers eschew the download and installation of easily detectable malicious software. Instead, they use tools already installed on the target’s own computers — powerful and widely trusted system and security programs like PowerShell or Metasploit — to inject their malicious code directly into the computer’s working memory.

The commands to do this are typically hidden in an attachment, abusing a functionality like Visual Basic, Object Linking or — as in last week’s example — Dynamic Data Exchange or DDE. It is these attachment lures that the Morphisec researchers analyzed for their timeline.

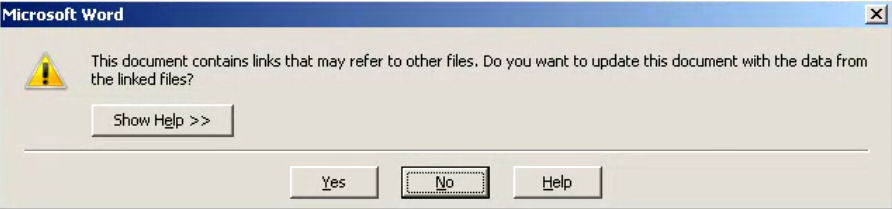

The lures rely on social engineering — Microsoft users will generally get a pop-up box asking them if they want to “enable content” or “update links” in the document they’re opening — and are typically spear-phished very carefully at a small number of targets.

The kind of pop-up window displayed by malicious Word attachments using fileless malware

Earlier this year, FIN7 was suspected of being behind an attack that used emails appearing to come from the SEC’s Electronic Data Gathering, Analysis and Retrieval (EDGAR) online filing system. The emails bore a Microsoft Word attachment titled “Important changes to form 10K.”

A 10K is a form that public companies have to submit to the SEC every year, and the targets were people involved in their company’s filings — often meaning their email address was listed on public documents.

Last week, researchers at Cisco Talos saw spear-phishing emails, with a similarly spoofed SEC address, bearing an attachment that used DDE to launch a “complex multi-stage infection process,” typical of FIN7.