When your apps are dormant, you become a more likely target for crooks

If you have banking or e-commerce apps you haven’t opened in months, it’s a good time to make sure no one else is using them, either.

Sixty-five percent of accounts that experience an account takeover attack — when an outsider logs in with a victim’s own username and password — have not been accessed by their true owner in more than 90 days, according to forthcoming research from DataVisor, a California-based startup specializing in fraud detection. When an account is dormant for awhile, it’s easier for a crook to use an unsophisticated method to get in, take what they want and get out before they’re caught.

It typically works like this: Thieves gather usernames and passwords leaked in previous breaches of popular sites. Then they enter the information into automated tools, which submit those stolen credentials into dozens or hundreds of apps. Successful hits give attackers the means to steal money, use customer loyalty points or temporarily hijack a social media account for other means.

“The takeover (and often the subsequent fraudulent activity) usually goes unnoticed by the dormant user, as they are not actively managing their account,” according to the DataVisor report. “Additionally, the online service where the account is registered may not have enough information about the user to detect that there is a change in the account behavior. Without a track record of activity, it is more challenging to identify suspicious anomalies.”

DataVisor’s figures, included in research shared with CyberScoop prior to a scheduled release in early July, provide the latest insight into how scammers use account takeover (ATO) attacks. The company didn’t specify the time frame for its research, nor did it disclose the apps or services it examined.

The numbers, however, are illuminating. Even a month is a dangerous amount of time. While 65 percent of the affected accounts hadn’t been accessed in 90 days, 80 percent belonged to users who hadn’t logged in to their page in more than 30 days.

The scope of the problem is affected by other factors, too, as other researchers have noted. Most Americans use multiple social media accounts, and the average email address registered in the U.S. is tied to 130 different services, according to the password management firm Dashlane.

There are two common techniques for testing stolen username/password combinations: “Credential stuffing,” in which scammers plug leaked credentials into as many services as possible, and “password spraying,” a more imprecise attack that occurs when hackers use scripted bots to test commonly-used passwords against random usernames.

“Unlike normal human activities, which exhibit diurnal patterns corresponding to awake/sleeping hours, the scripted nature of the fraudulent activities means that they can take place at all hours of the day, consistently.”

Hitting dormant accounts quickly

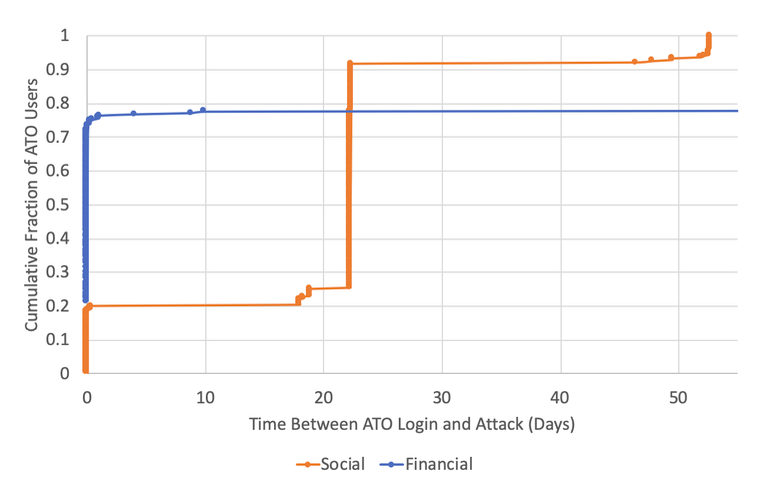

After a successful ATO, an attacker behaves much like a common purse thief who wants to make big purchases quickly in case the victim does notice the crime. Researchers found that 72 percent of the financial accounts made fraudulent transactions within an hour of their initial compromise.

All of those transactions add up. ATOs have emerged as a major problem for big businesses, resulting in $4 billion in fraud last year, down from $5.1 billion the year before but still double the 2016 total, according to Javelin Strategy’s annual identity theft report. Last year, Starbucks’ chief information officer said the coffee seller suddenly had to outsource much of its security work upon learning that roughly 20 percent of the username and credentials for sale on the dark web, like the 117 million credentials stolen from LinkedIn, for instance, could be used to infiltrate Starbucks customer accounts, thanks to password re-use.

Corporate loyalty points have proven valuable on the dark web, and appear to be the motivation behind security incidents like the one last year affecting Dunkin’ Donuts, when the chain warned customers their DD Perks information had been compromised.

It’s different for social media accounts, where hackers can afford to linger for some timebefore they risk exposing themselves by taking action. In one large attack, DataVisor found, 81 percent of the compromised accounts started posting spam and attempted scam messages three weeks after initially logging in.

Researchers dubbed this technique “account incubation,” a method that’s especially hard to detect because scammers’ activity may have mingled with the true account owner.

A DataVisor graphic demonstrates the speed at which thieves utilize illicit account access.

Some other key points from the recent research:

• Twenty percent of the compromised financial accounts were accessed within 300 miles of the actual account holder’s registered location, a goal hackers can achieve by rerouting their internet connection through a local connection, or otherwise masking their true location.

• Fraudsters who broke in to social media accounts appeared to be within 300 miles 3.4 percent of the time, the report found, perhaps evidence that financial services take use more rigorous security protocols social media firms do not.

• As more users begin to rely on their phone as an authentication techniques, scammers also are going mobile. Last year, 17 percent of ATO victims had their phone accounts taken over, up from 10 percent the year before, according to Javelin. Analysts blamed fraudsters’ need for access to a user’s phone, and their SMS text messages to subvert multi-factor authentication controls, as the reason for that uptick.

“Not only do businesses have to defend against the bad actors, but they also have to simultaneously protect their good customers,” DataVisor researchers wrote. “If a good customer’s account gets hijacked, they need to have confidence that they will be protected before any damage can occur.”