How China used Western social media for a late-2018 charm offensive

More than 40,000 English-language social media posts that originated with six state-run Chinese media agencies reached millions of users on Instagram and other services over a span of four months concluding in January, according to research published Wednesday by the threat intelligence company Recorded Future.

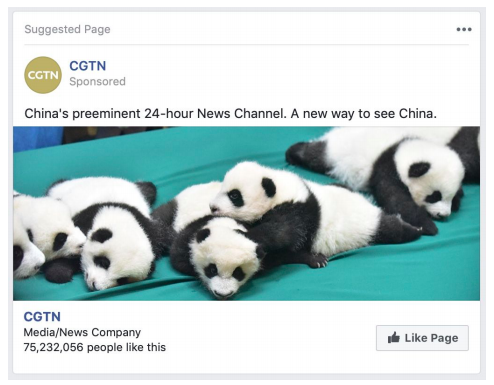

Xinhua, People’s Daily and others sought to subtly manipulate public opinion in the U.S. by promoting flattering images of Chinese culture, including tourist destinations and panda bears, rather than copying the hard-line rhetoric typically found in the Chinese-language versions of the same outlets, according to Recorded Future. Verified Instagram accounts run by both of those services posted roughly 26 times a day, reaching more than 5 million users between October 2018 and January.

The effect is to overwhelm social media users in the West with positive images about China, potentially eroding their ability to think critically about a government that has been accused of committing human rights abuses and perpetrating a vast, generation-long cyber-espionage campaign against Western organizations.

In many cases the ads were flagged as political disinformation only after their run-time had ended, meaning users would have had no way of realizing they were viewing propaganda, said Priscilla Moriuchi, director of strategic threat development at Recorded Future.

“China’s goals are to gain global influence, and further the idea of an idealized Chinese Dream,” she said. “Xinhua and People’s Daily are presenting a bias, distorted view of the news. That is the definition of disinformation.”

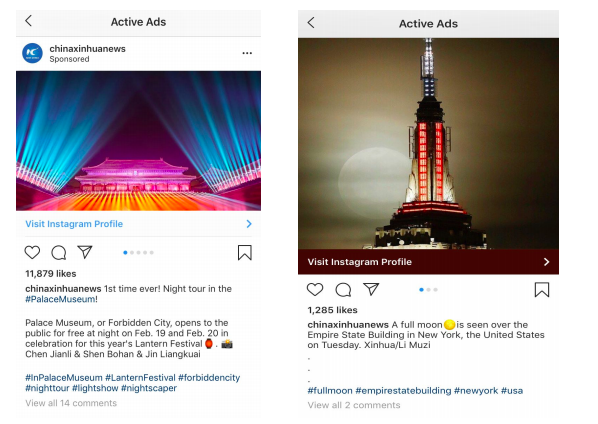

An example of Chinese state media seeking to influence Western social media users, according to Recorded Future (Image via Recorded Future).

Researchers also examined social media activity from China Global Television, China Central Television, China Plus News and the Global Times. The results highlighted the difference between China’s nuanced approach to political propaganda — where the goal is for Beijing to gain international influence — compared to that of Russia, which has sought to exploit political divisions in the U.S. and elsewhere to disrupt the global order.

“China likes the UN,” Moriuchi said. “They just want more control over it … [so] it’s them taking boring step after boring step until they achieve their ultimate goal.”

In one paid Instagram ad, Xinhua news posted a bright image of the Forbidden City, the former Chinese imperial palace in Beijing, with a caption saying the tourist destination “opens to the public for free at night on Feb. 19 and Feb. 20 in celebration for this year’s Lantern Festival[.]”

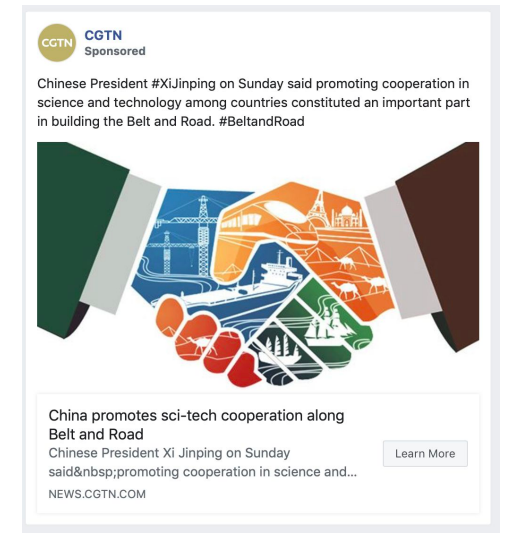

Others tempted users to click an article boasting of reforms President Xi Jinping has implemented during his tenure, or stories about how the government has promoted technological development as part of its $1 trillion Belt and Road initiative.

Chinese state media uses this image and others like it to improve the image of President Xi Jinping, according to Recorded Future (Image via Recorded Future).

Compare that to incendiary Russian posts released last year by the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence. In one post, the Russian authors suggested the Ku Klux Klan had infiltrated U.S. police departments “for years,” while another advocated an end to sanctuary cities.

Along with differing national goals, Chinese and Russian propagandists also took a different approach to spreading disinformation because of bureaucratic realities. Russian actors worked for the Internet Research Agency, a separate company more free to experiment with different memes and social media. In China, the state media agencies were under more direct control of leaders in Beijing, who have been unable to master U.S. popular culture, Moriuchi said.

“Governments really just aren’t funny,” she said.