Phishing kits are licensed, managed and pirated like any other legitimate software

Spearphishing schemes are pulling on practices from legitimate software companies in order to enhance the efficiency and distribution of their scams, according to new research published Wednesday.

Akamai Principal Lead Security Researcher Or Katz, whose company sees thousands of new phishing pages each day, and has noticed phishing kit sellers are increasingly operating as if they were in the lawful commercial space.

They are using “factory-like production cycle to target dozens of brands,” Katz, who has been analyzing the development of phishing kits since December last year, writes in the research.

One phishing kit distributor Akamai has been tracking advertises kits that imitate a wide swath of websites, including Gmail, Amazon, Facebook, YouTube, GoDaddy, PayPal and Skype.

“The threat posed by phishing factories isn’t just focused on the victims who risk having valuable accounts compromised and their personal information sold to criminals,” Katz writes. “These factories are also a threat to brands and their stakeholders.”

In one case, Akamai has caught one phishing kit on more than 1700 domains. That kit, which Akamai is calling “Chalbhai,” has targeted major brands including LinkedIn, Microsoft, Wells Fargo, Bank of America, and Chase.

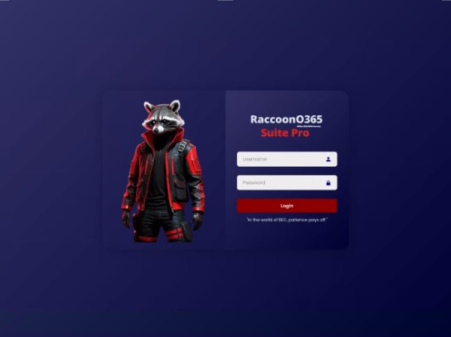

Some developers are building out their own registration and licensing systems in a mimicry of legitimate software licenses, Katz notes.

The Chalbhai developer has created a username and password system which includes personally identifiable information, including name, address, birthdate, Social Security numbers, and financial details, according to Akamai. One developer in particular, known as 16Shop, which specifically appears to target Apple users, also has its own licensing and registration process.

Just as in the broader economy, there are also those scamming the scammers behind the phishing kits. Known as “rippers,” these people seek to steal existing phishing kits, copy back-end functionality, and present them as their own. In some cases, Chalbhai appears to be the victim of one or more rippers, according to Akamai.

Concealing and evading

Akamai has also observed a few trends among phishing kit developers that seek to evade traditional detection. One tactic is the use of randomization generators to better target victims and to evade detection, according to Katz.

These generators create URLs so that in the event a phishing website is blacklisted, operations can avoid being neutralized in one fell swoop. Katz notes the randomization generator has an added benefit for the attackers — it can confuse victims.

“Random digits and letters often distract the victim and make the page appear more official,” Katz notes.

Other techniques include efforts to evade signature-based detection, which is traditionally used by security software to block phishing kits. Cybercriminals now constantly reiterate random HTML values so that security software would be forced to recognize new source code, which Katz notes is “nearly impossible.”

“When the victim loads the page for the first time, the odds are in the criminal’s favor that there are no pre-existing signatures on record for the page,” Katz writes.

Overall, Katz assesses some of these tactics have allowed spearphishers increasing success in their nefarious goals and in building out their ecosystem.

“Advancements made by defenders, including machine learning and algorithmic detection, place phishing kit developers at a bit of a disadvantage,” Katz writes. “Focusing on detection, and decreasing the lifespan of a given phishing kit’s deployment is an obtainable win in the security space.”