Astronomical costs, geopolitical headaches: Telecom fraud is too big to ignore, report says

International telecommunications fraud — a broad category that includes everything from consumer scams to corporate ripoffs — costs over €29 billion (roughly $33 billion) per year, according to a report published Thursday by Europol and Trend Micro.

The fraud isn’t just costly, it’s also endlessly frustrating for the companies and for law enforcement, the report’s authors say. The illicit activities range from tricking individuals into divulging their personal information to perpetrating international revenue share fraud — a complex scheme inspired in part by traditional money laundering techniques.

“Geopolitically, most telecom crime tends to be addressed by the telecom companies themselves,” the report states. “The costs are absorbed as the cost of doing business. This creates a kind of isolation, however. Without thorough cross-border intelligence sharing and intelligence fusion with law enforcement, the source, investigative method, and evidence cannot be connected in a way that results in a meaningful number of arrests or a decrease in the acceleration of international cyber-telecom fraud.”

SIM cards, for example, allow thieves almost to build their own criminal telecom infrastructure and route and it across various phones, the report states. Carriers implicitly trust their SIM cards. “[A]ny criminal collection of devices pushing traffic across SIMs will be successful merely by normally billable under one carrier, while any fraud performed is executed against another carrier in another country.”

Large-scale voice phishing — sometimes called “vishing” — campaigns also are among the most pernicious forms of international telecom fraud. The technique, familiar to anyone in the U.S. who received one of the estimated 48 billion robocalls last year, involves automated calls or human operators who convince call recipients to send them money. Victims typically are asked to provide their credit card number, but also their phone or bank account details.

Organized criminal operations carry out these schemes with call centers, often located in developing countries, that rely on SIM swapping, ID spoofing and outright threats to intimidate victims into turning over financial details.

The U.S. Justice Department last year announced it had broken up one ring, based throughout the country, that was active from 2012 to 2016. Scammers in some cases conned individuals out of thousands of dollars by posing at state police and immigration authorities who only would relent if they were paid.

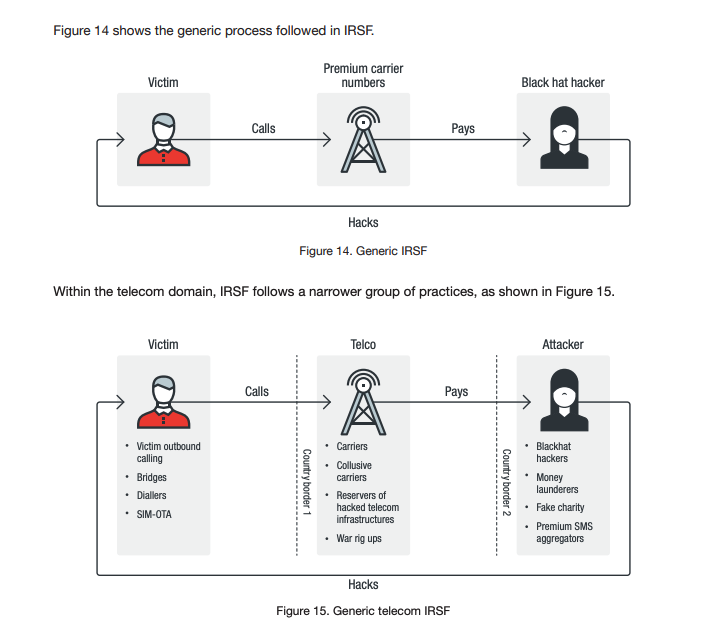

But hackers also use more technical advanced measures to defraud consumers and the telecommunication companies. Thieves abuse modern cellular infrastructure to use premium phone numbers to commit their fraud. Premium numbers are more difficult to trace, and cell hackers often charge premium fees to unsuspecting victims.

One common IRSF technique involves scammers purchasing a premium phone number that is available for sale in various online forums. The scammer then maintains control of that number, and uses it to target victims in other countries, exploiting gaps in telecom and police oversight.

By transferring value from one carrier to another IRSF schemes allow hackers to conduct attacks similar to traditional wire transfers in international banking, according to Europol.

“Since carrier logs show the path a ‘live’ call took, and those logs are kept for a short time, criminals simply can wait for the logs to expire before executing any further money laundering steps,” the report states. “The attacker can then perform IRSF on themselves to move the value from their own account under one carrier to an account under another carrier (they are unlikely to complain when they ‘victimize’ themselves).

“This way, the connection to the victim is obscured by the expired log. After a few weeks of these ‘hops,’ patient fraudsters will have broken much of the chain of evidence that might connect them to the original crime.”

IRSF fraud, as explained in a report published Thursday by Europol and Trend Micro (Europol).